Researchers Find Higher Intelligence Is Correlated With Left-Wing Beliefs and Seems to Be Genetic

Why Do Some People Embrace Change While Others Resist It?

Why do some people instinctively embrace change, while others cling tightly to tradition? What makes one person question authority while another seeks its reassurance?

We often like to believe that our political beliefs are the result of careful reasoning, spirited debate, or the lessons we’ve gathered from personal experience. But new scientific research is raising a more provocative possibility: that the foundations of our beliefs may run deeper than we realize — rooted not just in our experiences, but in the very ways we think, interpret the world, and perhaps even in our DNA.

This raises a compelling question: could your brain be quietly shaping your political views before you ever speak them aloud?

Can Your Brain Predict Your Politics?

A recent study set out to explore whether intelligence plays a role in shaping political ideology. The researchers analyzed data from over 300 families, including both biological and adoptive siblings, to see whether cognitive ability correlated with certain political leanings.

To measure intelligence, they combined two tools: traditional standardized IQ tests and polygenic scores — genetic scores that identify clusters of DNA variants statistically linked to traits such as educational attainment and cognitive performance. By integrating these measures, the researchers could examine not only expressed intelligence but also the genetic factors that may influence it.

One of the study’s strengths lies in its within-family design. By comparing siblings raised in the same households, the team controlled for environmental variables like parenting styles, socioeconomic conditions, and cultural exposure. The results were striking: even among siblings with nearly identical upbringings, those with higher IQ scores and stronger genetic indicators of cognitive ability tended to report more socially liberal and less authoritarian beliefs.

These patterns were consistent across six separate political attitude scales. As the authors summarized: “Polygenic scores predicted social liberalism and lower authoritarianism within families.” Importantly, the researchers stressed that intelligence does not dictate ideology. Instead, it appears to shape how individuals reason through complex political and social questions, potentially making them more comfortable with nuance and less reliant on rigid or binary thinking.

Thinking Styles and How They Shape Beliefs

Many people assume that political identity comes mainly from family values, community, or early socialization. While these factors matter enormously, research in cognitive psychology suggests that thinking style — the way a person naturally processes information — also plays a subtle but influential role.

One of the most studied traits in personality psychology is Openness to Experience, part of the widely accepted Five-Factor Model of personality. This trait reflects how receptive someone is to novelty, abstract concepts, and unfamiliar ideas. Studies published in Political Psychology have found that people with higher levels of openness often score higher on cognitive ability tests and, over time, tend to lean toward socially liberal ideologies. These individuals are more likely to engage with new information critically, ask unconventional questions, and explore a broader range of possible solutions when considering political or social issues.

On the other hand, researchers have studied a trait known as Right-Wing Authoritarianism (RWA). People with high RWA scores typically value stability, order, and tradition. They prefer clear rules and social hierarchies and are less comfortable with uncertainty or ambiguity. By contrast, individuals with higher cognitive flexibility often exhibit greater tolerance for complexity, showing a willingness to evaluate multiple viewpoints before settling on a position.

Crucially, these findings don’t suggest that one worldview is “smarter” or “better” than another. Rather, they highlight that people interpret the same information through different cognitive lenses, shaped by how their brains handle complexity and uncertainty.

Intelligence Is Only Part of the Story

While the data reveal a correlation between cognitive ability and certain political leanings, it’s critical to remember that intelligence is not destiny. It can influence how people engage with new information, but it doesn’t decide what they value most.

Psychologist Jonathan Haidt’s influential work on moral foundations theory illustrates this point well. Liberals often prioritize values like care and fairness, while conservatives tend to emphasize loyalty, authority, and tradition. These preferences are not indicators of intelligence levels but reflections of deeply ingrained worldviews and cultural identities.

Additionally, political orientation is shaped by a constellation of forces: family, community, education, personal experiences, and even pivotal moments in history. Two people with equal cognitive ability might arrive at opposing conclusions simply because they understand the purpose of society — and the role of government — in fundamentally different ways. Intelligence may help individuals navigate complex issues, but values ultimately guide where they land.

What Smarter Thinking Looks Like in Everyday Life

In today’s polarized climate, political conversations often feel tense or unproductive, even when both sides care deeply about the issues. One reason may be that people differ not only in values but in how they process complexity in the first place.

Cognitive and behavioral science show that all humans — regardless of intelligence or ideology — rely on mental shortcuts, or heuristics. We trust familiar sources, cling to narratives that feel safe, and sometimes evaluate arguments more by how they make us feel than by their logic or evidence.

However, we can train ourselves to think more deliberately. Here are practical, research-backed strategies for fostering more reflective political thinking without abandoning your core beliefs:

-

Ask “how,” not just “what.” Instead of stopping at “what” you believe, explore how that belief formed. Was it through firsthand experience, repeated exposure, or deliberate analysis? Studies on metacognition — the ability to reflect on one’s own thinking — show that this practice leads to more informed, balanced conclusions.

-

Resist oversimplification. Complex problems rarely have simple answers. When uncertainty feels uncomfortable, people may gravitate toward black-and-white solutions. Practicing comfort with complexity can foster more flexible, nuanced thinking.

-

Engage with opposing views. Exposure to well-reasoned counterarguments can refine your own position and reveal blind spots. Research shows that reflective engagement with differing perspectives reduces polarization, even if it doesn’t change your core stance.

-

Watch for cognitive blind spots. We are all vulnerable to confirmation bias and selective attention. Awareness doesn’t erase these biases, but it reduces their unconscious power.

-

Value intellectual humility. Changing your mind in response to evidence is not a weakness. It’s a sign of cognitive flexibility, linked to better problem-solving, deeper learning, and more respectful dialogue.

When Belief Begins in the Brain

We often assume that our beliefs are built solely from what we’ve learned, seen, or experienced. But emerging research suggests something deeper: that the mental habits we bring to every situation — our tolerance for ambiguity, our comfort with complexity, our ability to question assumptions — may quietly guide the direction of our political leanings long before we make a conscious choice.

This doesn’t mean that intelligence or cognitive style predetermines your ideology. Instead, it highlights a subtle truth: the way you think may shape the questions you ask, the evidence you seek, and the answers you’re willing to consider.

If belief begins in the brain, then better thinking isn’t about “being right.” It’s about cultivating curiosity, embracing nuance, and being willing to look closer — even when what you find challenges your assumptions.

News in the same category

'Hostile' comet aimed at Earth could obliterate the world's economy 'overnight' if it hits

Iconic movie sequel delayed until 2027 after online sleuths 'guessed the plot'

Don’t Sleep With Your Pets

The Secret Meaning of the Letter “M” on Your Palm

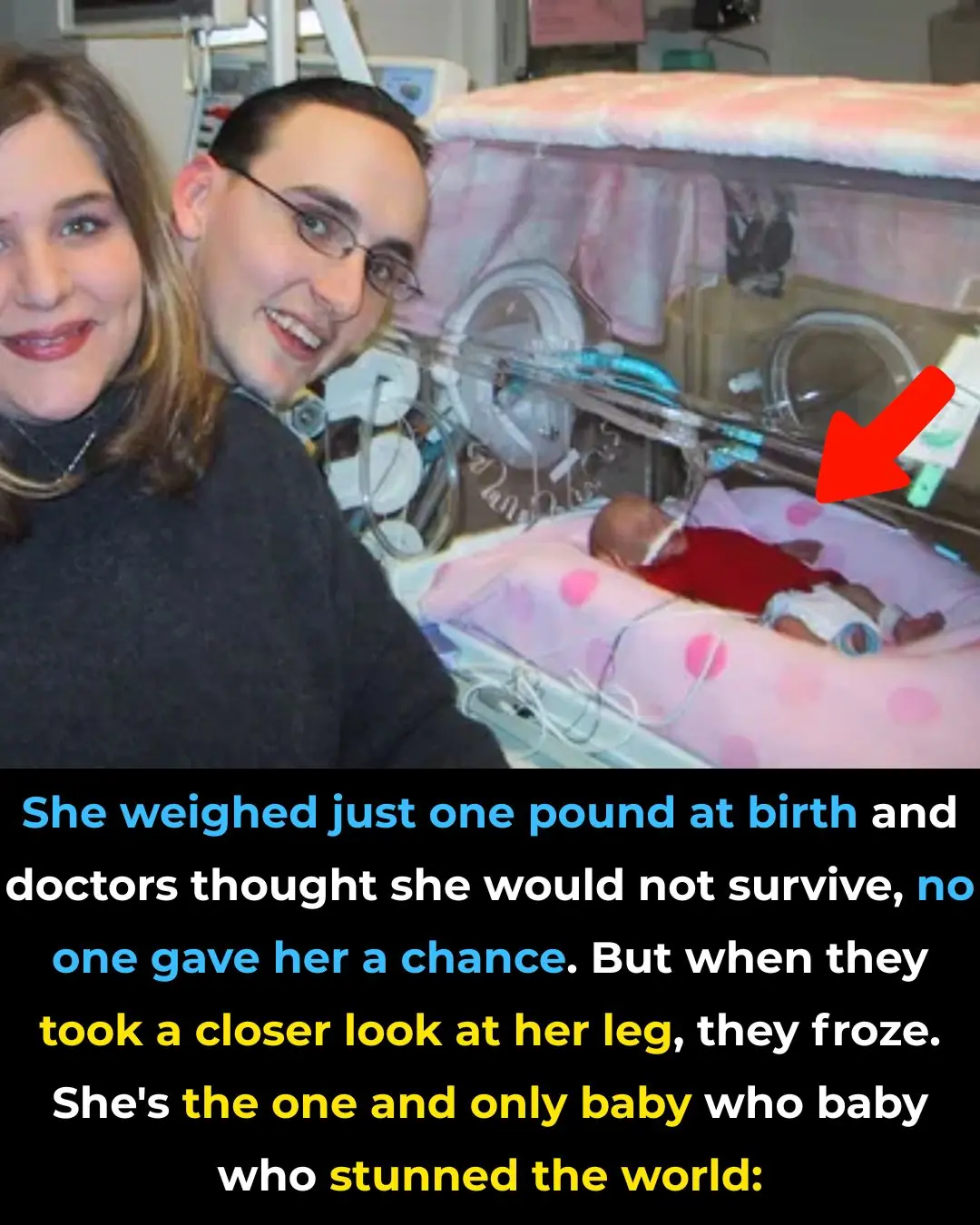

The Remarkable Journey of Tru Beare, Who Was Born Weighing Only One Pound

Researchers Create Injectable Hydrogel to Boost Bone Strength

If You Have Moles on This Part of Your Body

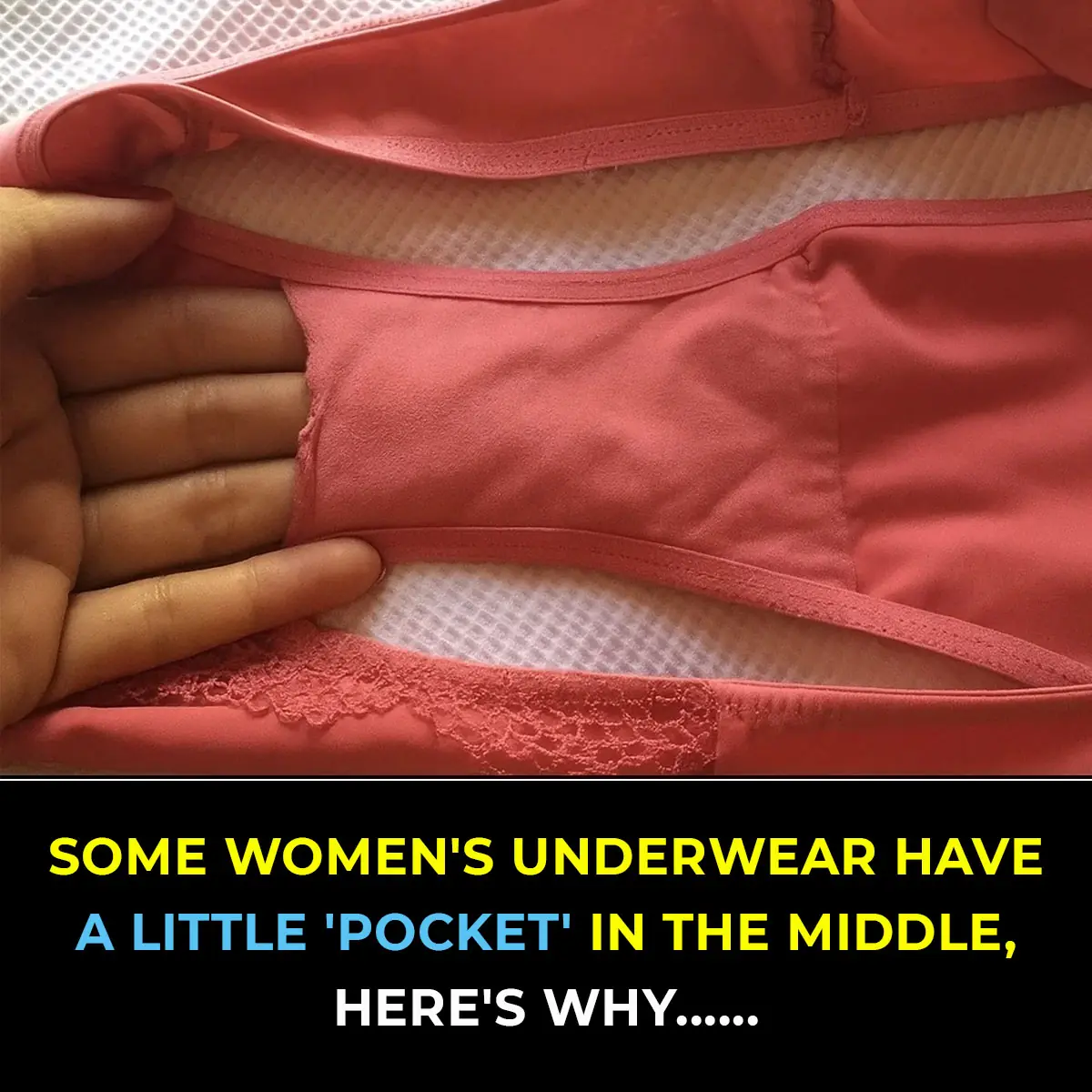

The Purpose of the Small Pocket in Women’s Underwear

Can You Spot the Hidden Number?

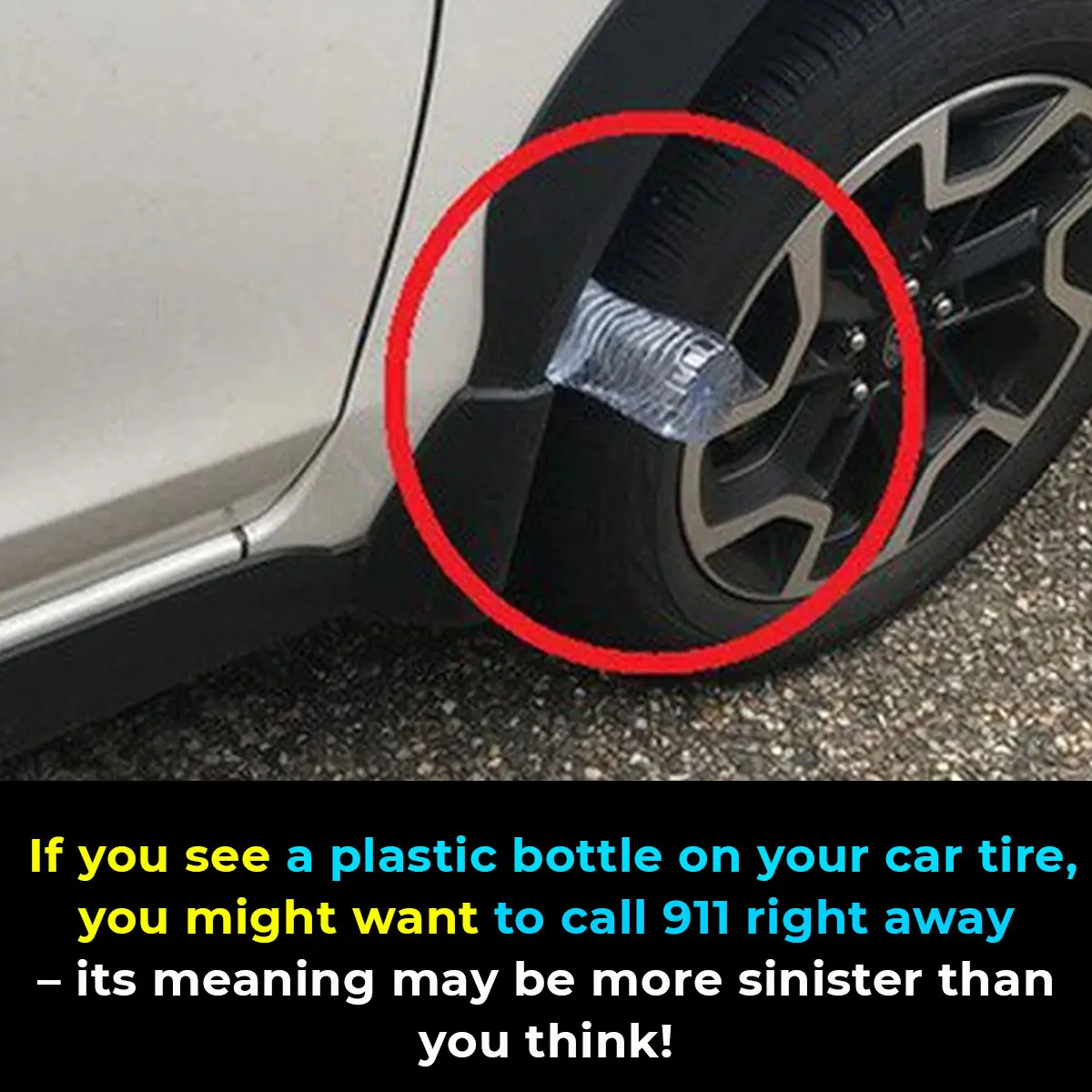

Beware of the Plastic Bottle Scam: A New Car Theft Tactic

Chinese Scientists Say They Created a Cure for Type 1 Diabetes

Rob Gronkowski forgot he invested $69,000 in Apple and ten years later the value has completely changed his net-worth

Scientists discover that powerful side effect of Ozempic could actually reverse aging

Scientists warn ancient Easter Island statues could vanish in a matter of years

NASA astronaut describes exactly what space smells like and it's not what you'd expect

Subtle Signs Your Passed Loved One Is Watching Over You

What Does a Thumb Ring Really Mean

Do Not Put These Things In The Freezer

News Post

Urgent Health Warning Issued After Pigs With ‘Neon Blue’ Flesh Are Discovered in One Specific Part of the Us

25-Year-Old Groom Dies from Acute Liver Failure After Eating Chicken – Doctors Warn of One Critical Danger!

Doctors caution people with pre-existing liver conditions, weakened immune systems, or chronic illnesses to exercise extra care when handling poultry and other high-risk.

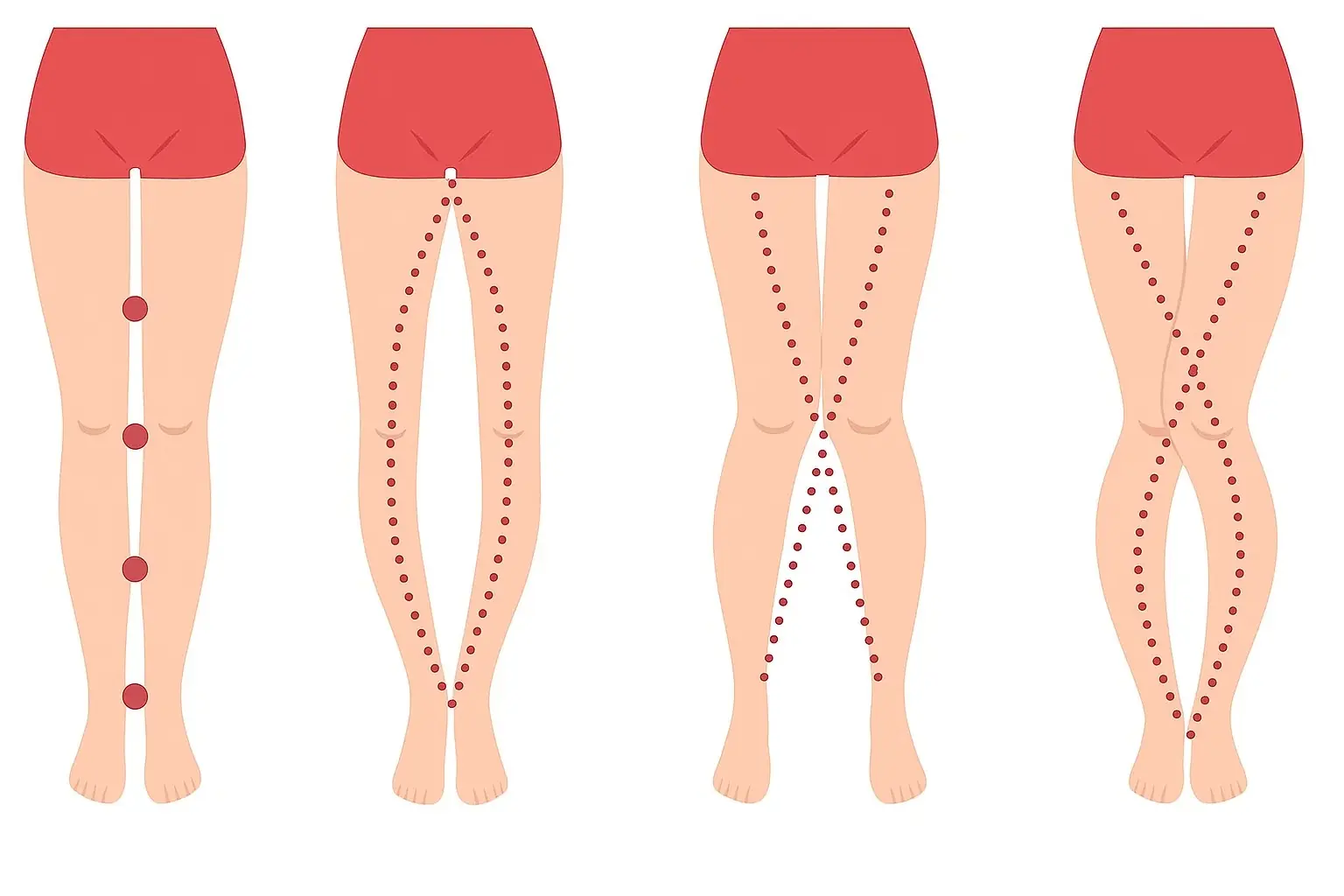

What Your Legs Can’t Say, Your Vagina Can — The Truth About the Female Body Most People Don’t Know

9 Areas Where Itching Could Signal Malignant Tumors — #7 Happens Most Often

The World’s Deadliest Food Kills 200 People Every Year — Yet 500 Million Still Eat It

Despite its deadly reputation, millions of people continue to eat this every day without issue.

Everything You Need to Know About Nighttime Urination And When To Start Worrying

Doctor Warns on TikTok: The Hidden Dangers of Kissing the Dying

Boosting Fertility: The Surprising Power of Lifestyle on Semen Quality and Reproductive Health

In many cases, the most effective solutions are already within reach—on your plate, in your daily habits, and in the way you manage your mental well-being.

3 Dangerous Habits of Husbands That Secretly Put Their Wives at Higher Risk of Cervical Cancer

Cervical cancer doesn’t just come from genetics or lifestyle — sometimes, it’s fueled by a husband’s hidden habits. These three common behaviors may seem harmless, but they silently put wives at serious risk if not stopped in time.

YouTuber shows crazy impact running 5k every day as a total beginner has on your body

Chilling moment Google's Gemini broke father out of delusion that he was 'changing reality' from his phone

'Hostile' comet aimed at Earth could obliterate the world's economy 'overnight' if it hits

Iconic movie sequel delayed until 2027 after online sleuths 'guessed the plot'

Wooden Cutting Board Got Black Mold? Skip the Soap—Do This 5-Minute Reset

Don’t Use Plain Water for Flower Arrangements

When Boiling Sweet Potatoes, Don’t Use Plain Water—Add a Spoonful of This for Softer, Sweeter Results

Don’t Thaw Fish by Putting It in Water

Don’t Clean Your Bathroom Mirror with Plain Water