The Underwater Geology of the Hawaii Islands is Just Amazing

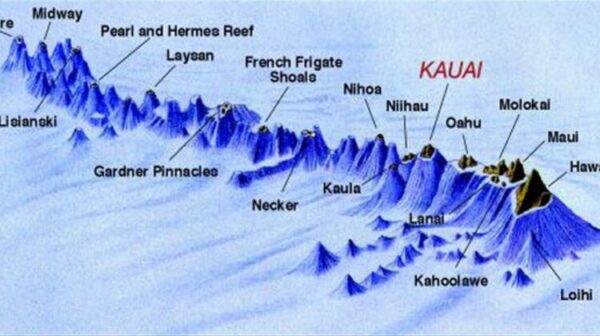

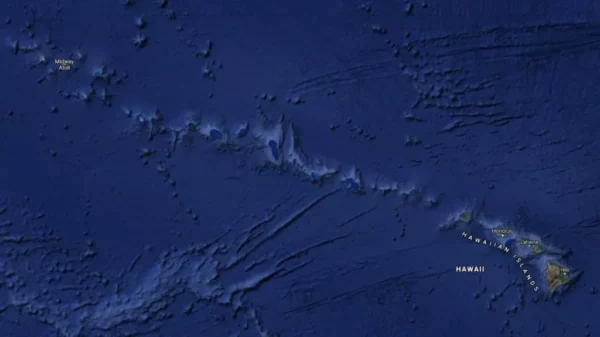

The Pacific Plate, one of Earth's massive tectonic plates, is slowly drifting northwestward at roughly the same rate your fingernails grow—just a few centimeters per year. While that may seem insignificant, this slow and steady movement over a stationary volcanic "hot spot" deep beneath the Earth’s crust has created one of the world’s most remarkable geological features: the Hawaiian Islands.

Over millions of years, this movement has generated a long chain of volcanic islands, forming one after another like an assembly line. This chain of islands, known globally as Hawai‘i, is the visible result of a deep, ongoing geological process that is still shaping the Pacific Ocean today.

Where Are the Hawaiian Islands Located?

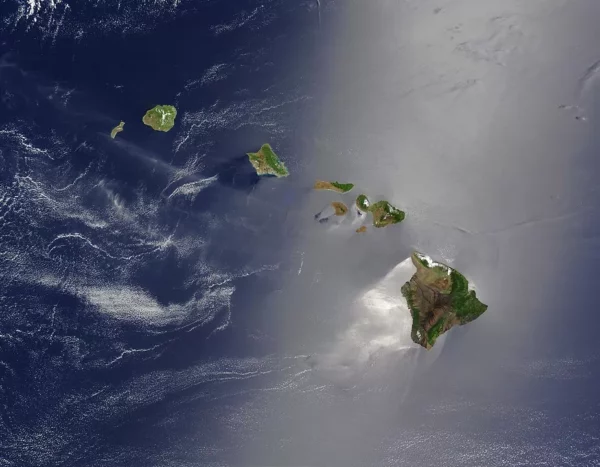

Situated near the center of the Pacific Plate, the Hawaiian archipelago stretches approximately 1,500 miles in a northwest direction from the southeastern tip of the Big Island toward Japan and the Aleutian Islands of Alaska. This impressive chain consists of eight major islands and 124 smaller islets, covering a total area of about 6,459 square miles.

The islands, from northwest to southeast, include:

-

Niʻihau

-

Kauaʻi

-

Oʻahu

-

Molokaʻi

-

Lānaʻi

-

Kahoʻolawe

-

Maui

-

Hawaiʻi (The Big Island)

Of these, the Big Island of Hawaiʻi is by far the largest, both in size and geological activity—and it's still growing.

How Were the Islands Formed?

The island of Hawai‘i, the youngest in the chain, formed over one million years ago. Interestingly, it emerged not as a single volcano but as five separate submarine volcanoes: Kohala, Mauna Kea, Hualālai, Mauna Loa, and Kīlauea.

Over time, repeated eruptions built up layers of lava, which overlapped and eventually merged the five volcanic structures into one island. Today, only Kohala is considered completely extinct. The others remain active or dormant, still shaping the island’s landscape.

The formation of the islands followed a clear geological sequence. As the Pacific Plate moved, each volcano formed when it passed over the hot spot. Once it drifted away, volcanic activity ceased, and erosion and subsidence took over.

A New Island in the Making

This volcanic process continues even now. About 18 miles off the southeast coast of the Big Island, an underwater volcano named Lōʻihi is actively erupting beneath the ocean's surface at a depth of 3,178 feet. In another 50,000 years or more, Lōʻihi could emerge as either a new island or become a sixth peak of the Big Island—depending on how it grows and merges.

The Major Volcanoes of the Big Island

The Big Island is home to five major volcanoes, each with its own characteristics and history:

Mauna Loa

-

The largest volcano on Earth by volume.

-

Covers about 51% of the island.

-

A shield volcano, with broad, gentle slopes formed by flowing lava.

-

Despite its size, it can be difficult to visually distinguish due to its low profile.

Kīlauea

-

One of the most active volcanoes in the world.

-

Located on Mauna Loa’s eastern flank.

-

Once thought to be a vent of Mauna Loa, it is now known to have its own magma chamber.

-

Considered the sacred home of Pele, the Hawaiian goddess of fire.

Mauna Kea

-

Covers about 25% of the island.

-

Known for its snow-capped peak during winter (its name means “White Mountain”).

-

From base (on the ocean floor) to summit, it rises over 33,000 feet, making it the tallest mountain in the world when measured from base to peak—even taller than Mount Everest.

Hualālai

-

Located on the island’s western side near Kailua-Kona.

-

Less active, but still considered a potential threat, with its last eruption occurring in 1801.

Kohala

-

The oldest and most eroded volcano on the island.

-

Extinct and heavily weathered, it features steep cliffs and lush valleys.

-

The dramatic Waipiʻo Valley, with its sea cliffs, likely formed from a massive landslide around 200,000 years ago.

The Larger Picture: Maui Nui and Greater Hawaii

Just across the ʻAlenuihāhā Channel, the island of Maui features Haleakalā, the world’s largest dormant volcano. Although it appears smaller than Mauna Loa or Mauna Kea, most of Haleakalā lies beneath the sea. Measured from its underwater base, it stands nearly 30,000 feet tall!

Haleakalā, which formed roughly 75% of Maui, last erupted in the late 1700s. Geologists believe that Maui was once part of a much larger landmass known as Maui Nui, which included the islands of Lānaʻi, Molokaʻi, and Kahoʻolawe. Over time, subsidence and rising sea levels caused the landmass to fragment into the separate islands we see today.

What Does the Future Hold for Hawaii?

Geologists agree that Hawaii’s story is far from over. As the Pacific Plate continues to drift, the Big Island will eventually follow the path of Maui Nui—subsiding, eroding, and fragmenting into smaller landmasses. New islands will eventually rise to take its place as the hot spot remains stationary beneath the moving crust.

For now, however, the Big Island is still very much alive. With Mauna Loa and Kīlauea both actively erupting in recent years, the island is still growing, adding new land as lava flows reach the sea.

The Hawaiian Islands are not just a tropical paradise—they are a living, breathing geological phenomenon. Their landscapes tell a story written in molten rock, sculpted by time, and still unfolding beneath the waves of the Pacific Ocean.

News in the same category

Little Pocket in Women’s Underwear

14 Items to Throw Away Right Now

Group finds spiky creatures in nest – shocked when they realize what they are

China’s “Pregnancy Robot” Claims Spark Debate — But Experts Say It’s More Myth Than Reality

Voyager 1: Humanity’s First Messenger to Reach a Full Light-Day Away

Earth’s Shadow, Moon’s Glow: The Total Lunar Eclipse of 2025

From Earth to Proxima Centauri: The Starship That Could Carry Generations Across the Galaxy

Woman 'who sold house' in fear world will end today explains why she's convinced 'the rapture' is coming

Unhappy iPhone users desperate to turn off iOS 26's four most controversial features after updating

Mariana Trench -The deepest location on Earth

The Trans-Canadian Rail Route: An Iconic Journey Across Canada

The Moon Is Slowly Drifting Further Away From Earth Each Year — A Physicist Explains Why

Clear Your Arteries Naturally: 7 Superfoods That Beat Aspirin for Heart Health and Longevity

By embracing a diet rich in leafy greens, garlic, berries, and heart-healthy fats, you not only prevent arterial damage but may also reverse early blockages.

Holy Basil (Tulsi) Secrets Revealed: The Ancient Ayurvedic Remedy for Cavities, Gum Disease, Bad Breath & Stronger Teeth

From fighting bacteria and soothing inflamed gums to reducing sensitivity, healing ulcers, and combating bad breath, Tulsi provides a safe, holistic way to protect your smile.

They Call It the “Bl:00d Sugar Remover”: The 100-Year-Old Remedy That Balances Glucose, Restores Kidneys, and Cleans Cholesterol Naturally

This 100-year-old remedy is not just a drink—it’s a living tradition that has survived because it works.

Iceberg Alley: Where You Can Watch Enormous Icebergs Drift in Front of Your Window

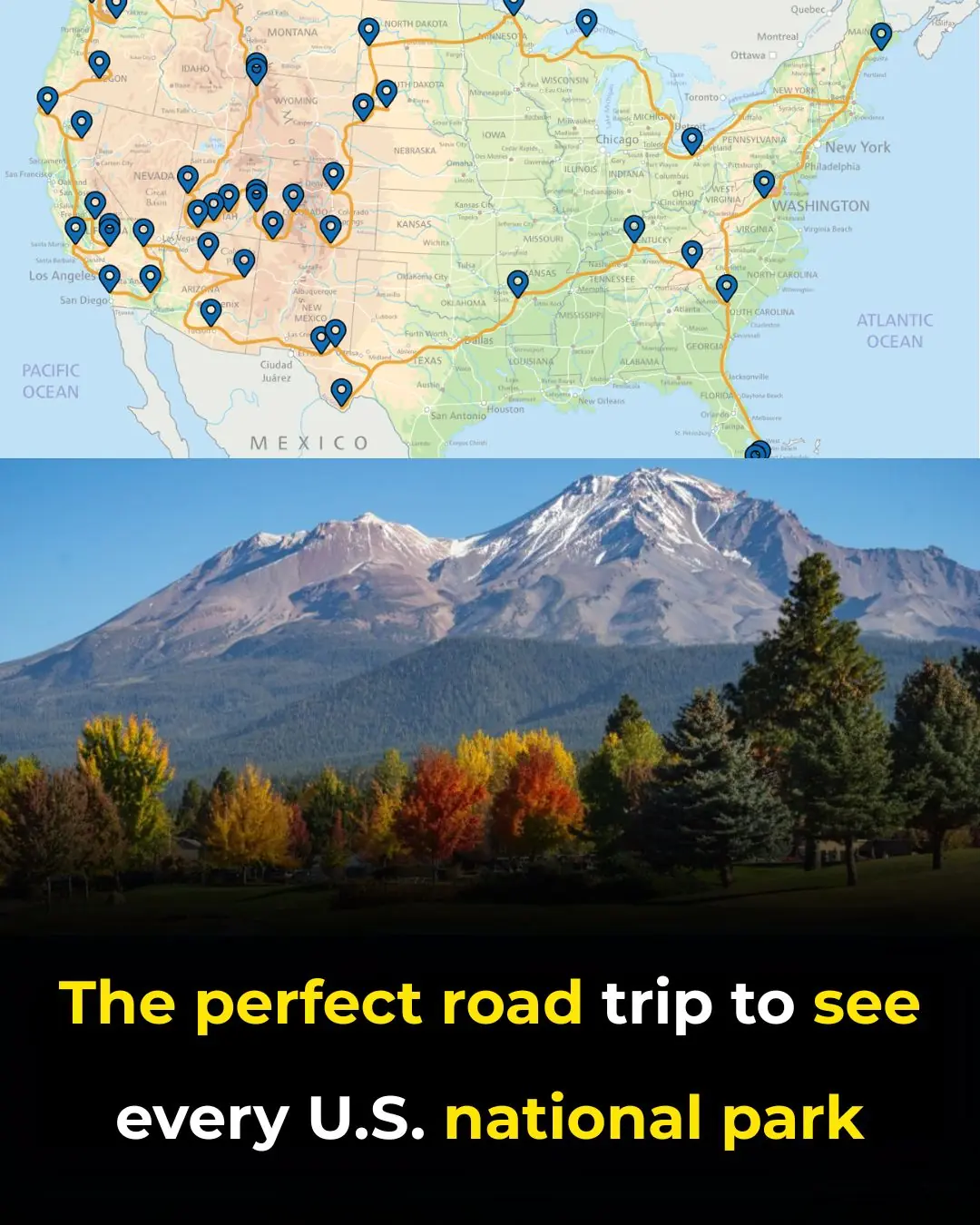

The Perfect Road Trip to See Every U.S. National Park

Man Accidentally Photographs The Real-Life ‘Angry Bird’

News Post

Forget 10,000 steps: Scientists prove 7000 steps gives you ‘almost identical’ life-saving benefits

The Most Effective Natural Way to Remove Gallstones

4 hidden signs of iodine deficiency in your skin, hair & nails

Objects People Were Confused About Their Purpose

Little Pocket in Women’s Underwear

What are the benefits of aloe vera? Here are 11 uses of aloe vera for health and skin

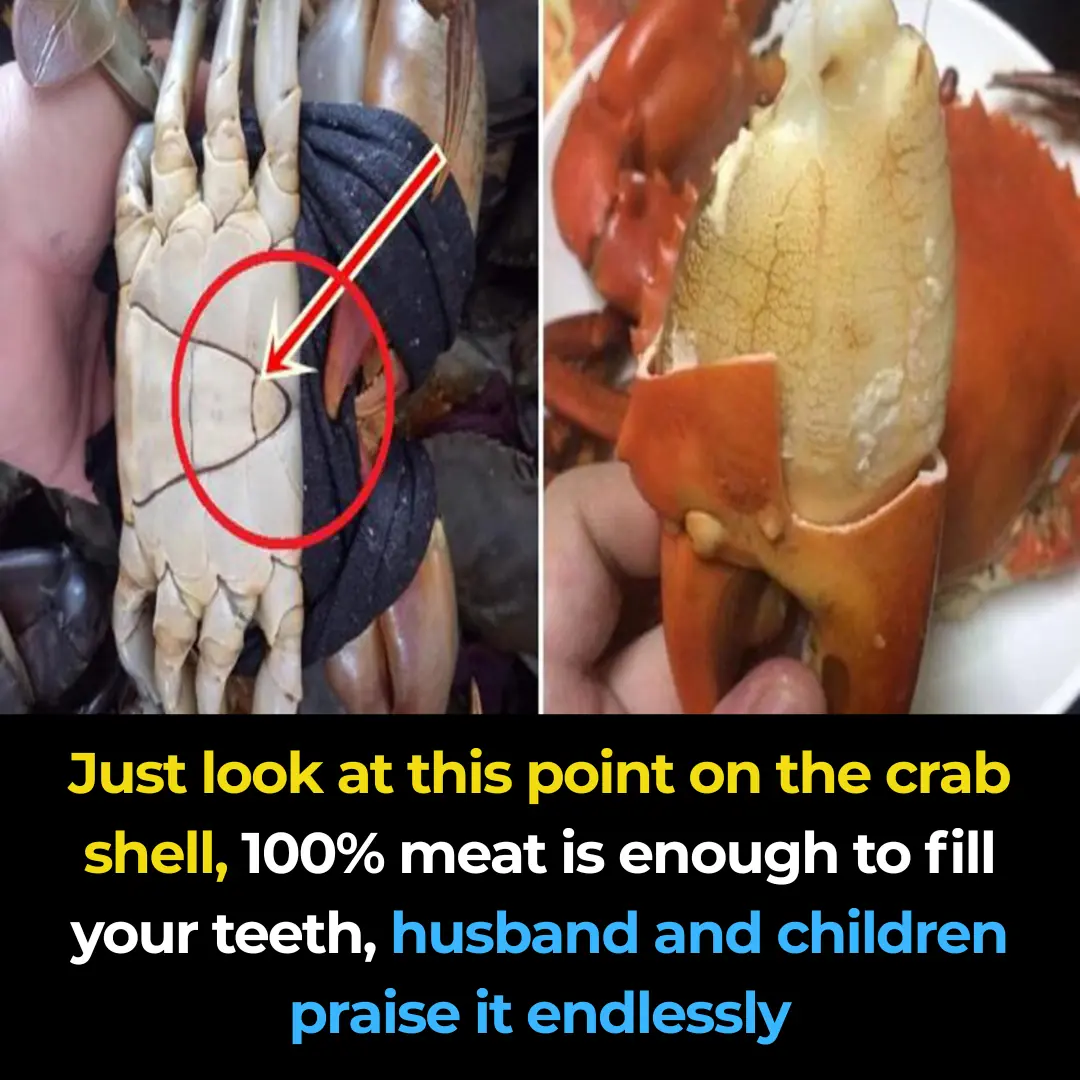

Just by looking at the spot on the crab's shell, 100% of the meat is packed to the brim, with my husband and children praising it non-stop.

These familiar fruits help improve sleep, especially number 1, which is both affordable and delicious.

Goosegrass: Health Benefits and Uses

7 Benefits of Chewing Raw Garlic on an Empty Stomach

Here's why you should never sleep with the bedroom door open. FIND OUT MORE IN THE COMMENTS ⬇️

Don’t Wash Your Wooden Cutting Board with Soap When It’s Moldy: Try This Simple Method to Make It Spotless in Just 5 Minutes

Mixing Essential Balm with Toothpaste: A Handy Tip Everyone Should Know, Both Men and Women Will Want to Follow Once They Discover It

They Call It the Blood Sugar Remover: The 100-Year Remedy That Heals Kidneys, Cleans Cholesterol, and Fights Diabetes Naturally

Top 5 Amazing Tips for getting rid of Blackheads and Whiteheads

14 Items to Throw Away Right Now

Group finds spiky creatures in nest – shocked when they realize what they are

The Purple Maguey Plant — Benefits and Traditional Uses

How to Naturally Kill The Bacteria That Causes Bloating And Heartburn