While the woman was doing a deep cleaning of the house, she came across an old letter from her deceased husband. Carefully unfolding it, she skimmed through the lines… and froze

Natalia sat at the edge of her husband’s hospital bed, barely breathing. Sergei Mikhailovich lay motionless under the white sheets — his once-powerful body now reduced to frailty by illness. The ticking wall clock measured out the minutes of his drug-induced sleep, which the nurse had mercifully administered half an hour ago. For Natalia, it was the only time she could rest her thoughts, if not her body.

She knew the moment wouldn’t last. It never did. The pain always returned — sudden and cruel, cutting through the morphine like a knife through gauze. But she was used to this waiting. She had learned to hold her breath when he did, to count every minute of peace like a borrowed miracle.

Sergei was fifty-six, and slowly wasting away. A liver transplant was his only real chance, but hope was fading. The waiting list crawled forward like a frozen clock. No family remained — no siblings, no cousins, no one to help or advocate. Just Natalia, always Natalia.

She stared out the narrow hospital window, watching rain trail down the glass. Her thoughts wandered, not toward the future, but backward — to the long road that had led them here. Life with Sergei had rarely been easy. But she had stayed. Through silence, cold shoulders, illness, and thankless routines, she had stayed. Years ago, she had whispered vows she barely understood: in sickness and in health, in poverty and in wealth. She hadn’t known how often life would test her on the former.

Natalia Korsakova’s story began in the summer of 1985, in a crumbling village surrounded by flat fields and stubborn people. After finishing eighth grade, she made a decision that felt like a rebellion — she would leave. The village, the dirt roads, the cow barns — all of it.

There was nothing for her on the collective farm. Especially after seeing what it had done to her mother, Lidia Vasilievna, a lifelong dairy worker with fingers twisted from years of frost and labor. Lidia’s day started at four in the morning — lighting the stove, boiling porridge, milking cows, feeding the goat they called Masha. The rhythm never changed. There were no weekends. Just exhaustion.

Natalia was an only child, raised by a mother who gave everything. But Natalia didn’t want to become her.

“I’m not milking cows for the rest of my life,” she declared one gray morning, her suitcase already packed. “I’m going to the city. I want concerts, heels, neon signs — not cows and compost.”

Lidia snorted, brushing flour from her apron. “The city isn’t waiting for you, girl. There’s a hundred like you on every corner. Finish school here. Be an agronomist. A vet, maybe.”

“Never,” Natalia replied sharply. “If I study, it’ll be in the city. I’ll come back for holidays, and then I’ll bring you with me. You’ll see.”

But Lidia didn’t believe her. And she didn’t want to leave. “She’ll fail and come back,” she thought. “She’ll need a roof.”

The truth was, Lidia knew her daughter too well. Natalia was lazy and impulsive. While her mother worked from dawn, she often slept past noon. Lidia had coddled her too long, and now the girl was spoiled and soft. But still, she let her go — because what else could a mother do?

Natalia arrived in the city with her two closest school friends — Galina and Irina. They enrolled in a vocational college and squeezed into a narrow dorm room, full of flickering lights and borrowed furniture.

Reality hit hard. Within weeks, Natalia realized the village — with its clean food and quiet skies — hadn’t been so bad. The city was gray and sharp, full of people too busy to care, and prices that made her dizzy. But pride wouldn’t let her turn back. “If others can survive here, so can I,” she told herself in the dark.

In the beginning, she was terrified to walk alone at night. But over time, she adjusted. They found cheap concerts, snuck into dance halls, and flirted with musicians near chain-link fences around stadiums.

One evening, fate introduced her to Leonid Pavlov, a charismatic music student with a crooked smile and an expensive guitar. He was charming, confident — everything the village boys weren’t. That night, she let herself believe she was living a song.

But dreams have consequences. The pregnancy was unexpected. The abortion was quick. And the damage — permanent. Natalia didn’t know it then, but she’d sacrificed her future for a boy who never called again. For years, she buried the regret deep inside her, like a splinter she refused to remove.

By the time Natalia turned twenty-five, she had built a new life. After college, she found work as a sales clerk in a large supermarket during the chaotic early '90s — when shortages were rampant, and real goods hid behind “special” counters for the right buyers.

Eventually, she landed a job in a food warehouse. On her first day, she was stunned. Piles of sugar, crates of meat, boxes of goods — while shop shelves stayed empty. “This is the heart of the system,” she realized. “This is where power hides.”

And so, Natalia adapted. She learned to navigate the web of unofficial deals and unspoken rules. She made contacts, kept a black book full of favors. Within five years, she had a two-room apartment and a used Lada — unthinkable luxuries in her childhood. She had climbed higher than anyone had expected.

Her mother, who Natalia had eventually brought to the city, was less impressed.

“Natalia, how much junk do you need?” Lidia muttered, frowning at a new stack of handbags. “Is that your happiness?”

“Oh, Mama, come on,” Natalia smiled. “Happiness is not having to worry about the basics. I can buy what I want. I brought you here, didn’t I? No more village, no more three-kilometer walks to the clinic. I drive you now, like a queen.”

“Happiness,” her mother sighed, “is family. Children. A good man. You’re nearly thirty. Where’s your family?”

Natalia turned away. Her mother didn’t know the truth — about the abortion, the infertility, the deep emptiness that no apartment could fill. She let her mother believe in some mythical future where a real love would arrive and give her grandchildren. It was easier that way.

In reality, Natalia had spent years entangled with Arkady Leonovich, a married shoe factory director nearly twice her age. He bought her silence with jewelry and Italian shoes, with promises whispered and always delayed. Her luxurious life had been built on borrowed time.

And then he left — quietly, suddenly. Emigrated to Israel with his family, without warning her. Without a word.

She was fired soon after. No job. No money. Just a car and an apartment that felt too quiet. For the first time in years, Natalia had to start again — not just financially, but morally. Something inside her shifted.

She promised herself: no more foolish affairs. No more love without guarantees. This time, she would marry. But not just any man — someone wealthy, kind, and most of all, someone who wouldn’t expect children.

Finding such a man was like looking for gold in a sandpit.

But then, she met Sergei Mikhailovich Glinsky — a calm, well-dressed man with a distant gaze and steady income. He wasn’t charming, not exactly. But he was stable. Dependable. He didn’t talk about children. He barely talked about anything, really. But he offered security. And that was enough.

Natalia became Natalia Glinskaya.

Now, sitting by his hospital bed, Natalia wasn’t sure what she felt. Loyalty? Pity? Resentment? The years had melted away like snow on asphalt — fast, colorless, without ceremony.

Sergei stirred slightly, muttering in his sleep. His lips moved as if whispering to someone far away. Natalia reached out and gently adjusted the blanket.

“Rest,” she whispered. “I’m still here.”

And for now, that was all she could offer.

However, that very shop soon became the target of local racketeers, and the business was simply taken away. Varvara was shocked. Anton just shrugged and showed no sign of distress. Gradually, Varvara began to understand that her husband’s money was not earned. He neither knew how to earn it nor how to manage it wisely.

Most likely, the funds were inherited or obtained by chance, or maybe even illegally. Varvara had no other explanation. Anton had no relatives, no friends either — at the wedding, only the neighbor Igor attended from the groom’s side, since no others were found.

After the wedding, the newlyweds moved into Anton’s three-room apartment. Varvara brought her mother, Valentina Egorovna, and her husband didn’t object. Varvara rented out her old apartment, and sold her mother’s house in the village. She understood she couldn’t count on her husband — he was clearly no new Count of Monte Cristo. As soon as the money ran out, she’d have to start over again.

It was then that Varvara got down to business. Having sold the house in the village, she opened a small bakery. The bread sold quickly; demand was high. Then she launched a bread stall at the market, and later mastered making French baguettes and croissants.

Varvara didn’t become rich, but she didn’t know want either. She wasn’t interested in large-scale business — it was enough to have a calm life. At least, in case of a divorce, she could live comfortably with her mother.

The couple lived strangely — each seemingly alone. Anton was silent, thoughtful, sometimes even sullen. Money apparently did not bring him joy. He spent it easily, not thinking about tomorrow. They hardly ever had heartfelt conversations.

How many times Varvara asked where he got such funds — Anton either dodged the answer or got angry. Varvara felt some heavy burden lay on her husband’s soul but could not understand what tormented him. Only once, ten years after their wedding, Anton opened up a little.

It happened during a vacation at a country house by a lake. They were celebrating their dating anniversary. September was warm, the Indian summer had come. At dinner by the campfire, after a few glasses of wine, her husband began to tell:

“My native village is also by water, but not a lake, a river. Around — forests… And what mushrooms in autumn — caps the size of two palms. Berries — everywhere, as if someone scattered them specially. In childhood, Andrey and I ran into the forest every morning, picked berries, and sold them to the state farm.”

Varvara was afraid to move, afraid her husband would stop talking. But he continued:

“Andrey and I also loved fishing. Sometimes we took Masha with us, but rarely. She mostly helped mother at home. Our mother went to the market early in the morning, and the household was on Masha.”

“Who are Andrey and Maria?” Varvara thought. “Brothers? Neighbor kids? Whose mother went to the market — Anton’s or those mysterious children’s?” But she kept silent, listening on.

“When the salmon spawned — pink, chum, sockeye — it was beautiful. We carefully gutted the fish, took out the roe, rinsed it, and put it back inside, sprinkled with salt. In the morning, we ate fresh roe.

Once, Andrey and I were riding our bikes on a bridge, and a bear came toward us. The bridge was narrow, no way to turn around. We stood, watching it, it watched us. I was scared to death and shielded Andrey. I thought it was the end. But the bear backed off, left the bridge, and went into the forest. Only then did we breathe a sigh of relief.”

“Who are Andrey and Maria?” Varvara quietly asked. “Are they your brother and sister?”

Not knowing what he was saying or realizing what he was revealing, Anton continued his path to confession…

Anton suddenly seemed to come to his senses. As if a sober awakening hit him on the head — he sharply came out of his memories, frowned, and said sharply:

“Go to sleep, Varvara. I have no relatives. How many times must I say it? Leave! I’ll stay a bit longer,” he said, refilling his glass with wine.

Varvara Semyonovna got angry. Why did her husband keep her in the dark? After all, she was not a stranger, but his wife!

“But how? You had parents, you didn’t just come from nowhere. You weren’t found in a cabbage patch, were you?” Varvara raised her voice.

“Maybe I was found in a cabbage patch. What’s it to you?” Anton shrugged.

In fact, Varvara was not very concerned about her husband’s relatives. Sometimes, curiosity overwhelmed her: what was Anton hiding? Why did he get angry when asked about his past? Sometimes this secret troubled her, and she even tried to find traces of the Glinsky family.

From documents, Varvara knew Anton’s parents’ names, learned that he was born on Sakhalin, studied there, served in the Navy in the Far East — and then everything stopped. She tried to find the Glinskys but soon gave up: “Why do I need this? My husband doesn’t want it, so neither do I. I have enough worries myself: mother is ill, her blood pressure fluctuates, and the business needs attention.”

Life doesn’t stand still — it moves forward rapidly, especially in the second half of life. And Varvara began to think about the value of time, about what’s important and what’s not. It became increasingly painful for her to hear children’s laughter, to see mothers with children on the playground. Her heart ached with the desire to be one of them.

Over the years, Varvara learned to appreciate her silent and sullen husband, especially after her mother, Valentina Egorovna, passed away. People say a person feels like a child as long as their parents are alive. After they’re gone, life changes, becomes different.

Now Anton was Varvara’s only close person. With him, there was no such terrible loneliness. This eternal grumbler and gloomy husband suddenly became her kindred soul. And the woman often regretted that they never became parents.

News in the same category

Their daughter disappeared in 1990, on the day of her graduation. And 22 years later, the father found an old photo album

We'll live off our daughter-in-law; she has a good job," the mother-in-law shared with her friend

If she needs money again, let her call the bank, not me, — Maria snapped, deleting her mother-in-law’s number from her phone

This Girl Spent 6 Years Fixing Her Jaw & After the Final Surgery, She Stunned Everyone with the Results – Her Transformation in Pics

'Mom, Do You Want to Meet Your Clone?' – What My 5-Year-Old Said Uncovered a Secret I Wasn't Ready For

You’re nobody without me,» my husband declared. But a year later, in my office, he begged me for a job

An eight-year-old child saved his sister during a severe snowstorm. But where were their parents at that time?

We’ll live off our daughter-in-law; she has a good job,» the mother-in-law shared with her friend

Lenočka, pay the utility bills. You have the money,” the mother-in-law asked again

Tired and confused, she spent the night at the station, having run away from her son and with no idea where to go

There’s a man hurting a girl!» — the child screamed, terrified, grabbing her mother’s hand. Lena glanced toward the bushes… and felt a chill run through her. Her heart froze

Your bonus is very timely, your sister needs to pay rent for the apartment six months in advance,” the mother ordered

Andrey sat opposite Olga, tapping his fingers on the tabletop.

A 70-year-old elder let a stranger stay overnight — at night, the village woke up to her screams. When they found out what happened, they shuddered

I found a little girl by the railroad tracks, raised her, but after 25 years her relatives appeared

A woman left a baby at the doorstep of an orphanage in the freezing cold. But after some time…

After 25 years, the father came to his daughter’s wedding — but he was turned away… And moments later, the crying spread among everyone present

Honey, I gave your sister the trip voucher, she needs it more — she’s going through a crisis, — her husband blinked innocently, having stolen his wife’s vacation

News Post

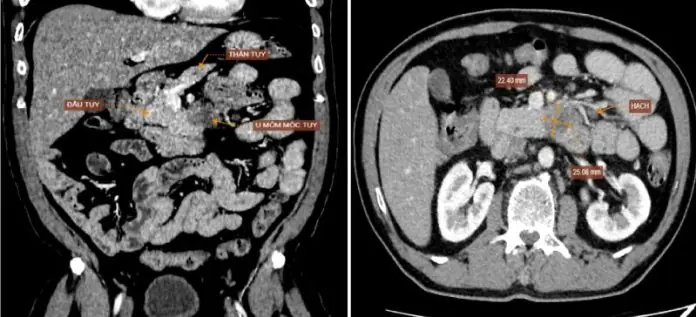

Afraid of Surgery, the Woman Used This for 6 Years to Shrink Her Tumor Based on a Tip – Oncologist’s Four Words Left Everyone Stunned

Discovered to Have One of the Deadliest Cancers After Just One Warning Sign

The Surprising Benefits of Drinking Turmeric Water at Night: 8 Reasons You Should Make It a Habit Today 🌙

Cloves, Ginger, and Lipton Tea: A Health-Boosting Trio Worth Gold

New Tiny Machine Removes Cholesterol from Arteries Without Surgery

Powerful Simulation Reveals How Cancer Progresses and Ultimately Causes Death

At My Husband’s Birthday Party, My Son Pointed and Said, 'That’s Her. The Same Skirt.'

My Husband Took Me on a Surprise Cruise — But When I Opened the Door, Everything Fell Apart

My Wife Found a Midnight Hobby – It Nearly Drove Our Neighbors Away

I Got Seated Next to My Husband’s Ex on a Flight – By the Time We Landed, My Marriage Was Over

One Day, I Saw a 'Just Had a Baby' Sticker on My Boyfriend's Car — But We Never Had a Baby

Never Throw Away Lemon Peels Again: 12 Unusual Ways to Use Them

How People Over 50 Can Supplement Fiber for Better Health

Unleash Your Inner Alpha: The Natural Nighttime Boost You Need

Stop Now! These 8 Pumpkin Seed Mistakes Trigger Irreversible Reactions in Your Body

The photograph of a little boy who became one of the most recognizable men today

Three Family Members Diagnosed with Thyroid Nodules – The Mother Collapses: “I Thought Eating More of Those Two Things Prevented Cancer”

A Family of Four Siblings Diagnosed with Stomach Cancer – Doctor Shakes His Head: Two "Deadly" Common Habits Many People Share

A 49-Year-Old Man Dies of Brain Hemorrhage – Doctor Warns: No Matter How Hot It Gets, Don't Do These Things