Meet James Hemings, the First French-Trained Black Chef Who Introduced These 4 Popular Dishes to Americans

James Hemings: America’s First French-Trained Chef and a Forgotten Culinary Pioneer

James Hemings’ story is both extraordinary and tragic—a tale of brilliance, bondage, and an enduring legacy that shaped the foundations of American cuisine. Born into slavery in 1765, Hemings was brought to Thomas Jefferson’s Monticello estate at just nine years old, alongside his mother Elizabeth Hemings and several siblings (Monticello.org). Jefferson inherited the Hemings family from his wife, Martha Wayles Jefferson, whose father, John Wayles, had fathered six of Elizabeth’s children. This made James Hemings, remarkably, both enslaved and Jefferson’s brother-in-law by blood. The Hemingses would become the largest enslaved family at Monticello, many serving as domestic workers, artisans, and skilled tradespeople (Smithsonian Magazine).

By 1779, Hemings and his brother Robert had become Jefferson’s personal attendants when Jefferson was elected wartime governor of Virginia. Historical records show that in 1781, when Benedict Arnold threatened to burn Richmond, it was the Hemings brothers who safely escorted Jefferson’s wife and children to safety (History.com). Jefferson occasionally allowed James to work side jobs and keep his wages, a rare privilege at the time—but one that didn’t change the fact that Hemings was still considered Jefferson’s property under law.

In 1784, Jefferson prepared to travel to France, newly appointed as U.S. Minister to the French Court. He chose to take Hemings with him, determined to have him trained “in the art of cookery.” Jefferson wrote from Paris requesting that Hemings meet him in Philadelphia, and together with Jefferson’s daughter Martha, they sailed from Boston on July 5, 1784 (The Washington Post).

Once in France, Hemings’ life transformed. He trained under the esteemed restaurateur Monsieur Combeaux and later under pastry chefs in Paris before earning a position as chef in the household of Prince de Condé. After three years of rigorous apprenticeship, Hemings became the head chef at Jefferson’s residence—the Hôtel de Langeac—then serving as the American embassy. There, Hemings prepared meals for diplomats, authors, scientists, and European aristocrats, his dishes bridging cultures and continents. He earned 24 livres a month (about $30 today), half the salary Jefferson once paid his former French chef, yet far more than any pay an enslaved man could earn in America (Monticello.org).

Despite his relatively privileged position, Hemings remained painfully aware of his enslaved status. He used part of his earnings to hire a French tutor and quickly became fluent, a skill that allowed him to move with rare confidence through Parisian society. France, during that period, was simmering with revolutionary ideals—calls for “liberté, égalité, fraternité” filled the streets, and enslaved people could legally petition for their freedom on French soil (Smithsonian Magazine). It remains unclear whether Hemings ever attempted to claim his freedom in court, but scholars suggest he may have been torn between the promise of liberty and loyalty—or fear—toward Jefferson.

When Jefferson returned to the United States at the dawn of the French Revolution, Hemings followed. In 1790, he made history again by opening one of America’s earliest documented restaurants, operating a small kitchen on 57 Maiden Lane in New York City (NPR). There, Hemings introduced refined French cuisine to an emerging American palate. Historians credit him with popularizing several dishes that remain staples today—macaroni and cheese, meringue, French-style fried potatoes (later “French fries”), and firm ice cream. These innovations would influence generations of chefs, though Hemings’ name was long omitted from culinary history (The Washington Post).

When Jefferson became Secretary of State, he took Hemings with him to Philadelphia. Hemings prepared dinners for presidents, European envoys, members of Congress, and Jefferson’s intellectual peers. His monthly pay of $7 matched that of free staff members—a recognition of his skill, if not his freedom. But living in Pennsylvania came with a new temptation: under the state’s gradual abolition law, any enslaved person who remained there for six consecutive months could claim their freedom (History.com). Records suggest Hemings exceeded that duration multiple times between 1791 and 1792, yet he never petitioned for emancipation.

In 1793, Jefferson finally drafted a formal manumission agreement:

“Having been at great expense in having James Hemings taught the art of cookery… if the said James shall go with me to Monticello… and shall there continue until he shall have taught such person as I shall place under him for that purpose to be a good cook, this previous condition being performed, he shall be thereupon made free.”

(Monticello Papers, 1793)

Hemings fulfilled his end of the bargain, teaching his younger brother Peter Hemings the culinary art. True to his word, Jefferson granted James his freedom on February 5, 1796. Afterward, Hemings traveled extensively and eventually settled in Baltimore, working as a chef for private clients.

By 1801, Jefferson had been elected President and hoped Hemings would return to the White House kitchen as a free man. Hemings reportedly agreed to serve again but requested that Jefferson personally write him regarding his employment terms. A letter from an intermediary, Francis Sayes, explained that Hemings wanted the offer “in [Jefferson’s] own handwriting.” Jefferson never did. Instead, he hired a French chef to replace him. Hemings briefly returned to Monticello later that year for six weeks of work, earning $30, before leaving for the final time.

Tragically, in October 1801, James Hemings died by suicide at just 36 years old. His passing shocked those who knew him—including Jefferson, who reportedly expressed grief at the news (The Smithsonian Magazine).

Though his life ended in sorrow, Hemings’ legacy continues to inspire. As the first Black French-trained chef in American history, he not only bridged two culinary worlds but helped define the early national cuisine of the United States. Today, scholars, chefs, and cultural historians celebrate him as a forefather of American gastronomy and a symbol of resilience, intellect, and artistry forged in the most oppressive circumstances.

Peace, love, light, and progress to the spirit of James Hemings—because of you, we can.

News in the same category

EXCLUSIVE: Kerry Katona 'upset' over 'selfish' Katie Price as cracks show in friendship

Big Brother fans fume ‘she can't get away with this’ as they slam housemate

12 Fruit Trees You Must Prune in August — and the Science Behind It

If You Find This Snake in Your Yard, Don’t Harm It — Here’s Why

Ooops, Guess I’ve Been Doing This Wrong: Why You Should Rethink Using Saucers Under Planters

1 Lemon Is All You Need to Revive an Orchid: Here’s How It Works

4 Good Reasons Everyone Should Read Ralph Ellison’s ‘Invisible Man’ At Least Once

Don’t Yank This from the Cracks: Why Dandelions Deserve a Second Look

Soap Water: A Gardener’s Secret Weapon for Natural Pest Control

20 Plants That Thrive in Cheap 5-Gallon Buckets

Strictly star Vicky Pattison left in tears after Motsi Mabuse’s comment

Strictly Come Dancing fans ‘gutted’ as Halloween Week results leak and fan favourite heads home

Ex-SNL star Leslie Jones reveals tense encounter with ‘a–hole’ director at ‘SNL 50’ party: ‘Get your f–king hand off me’

How Sydney Sweeney reacted to jokes about her chest at Matt Rife comedy show — alongside Scooter Braun

Complaints pour in over treatment of Strictly’s longest-serving judge Craig Revel Horwood

Meet Mary J. Wilson, The First Black Senior Zookeeper At The Maryland Zoo

Meet the Black Woman Who Created a Nail Polish Line That Caters to Darker Skin Tones

Meet the Compton Teacher Who Sparked Kendrick Lamar’s Love for Words

Autumn Lockwood Is The First Black Woman To Coach In The Super Bowl

News Post

Stop throwing out old hoses. Here are 10 brilliant hacks to use them around the house

Shaun Wallace’s heartbreak over tragic family death: ‘I watched him physically degenerate’

EXCLUSIVE: Kerry Katona 'upset' over 'selfish' Katie Price as cracks show in friendship

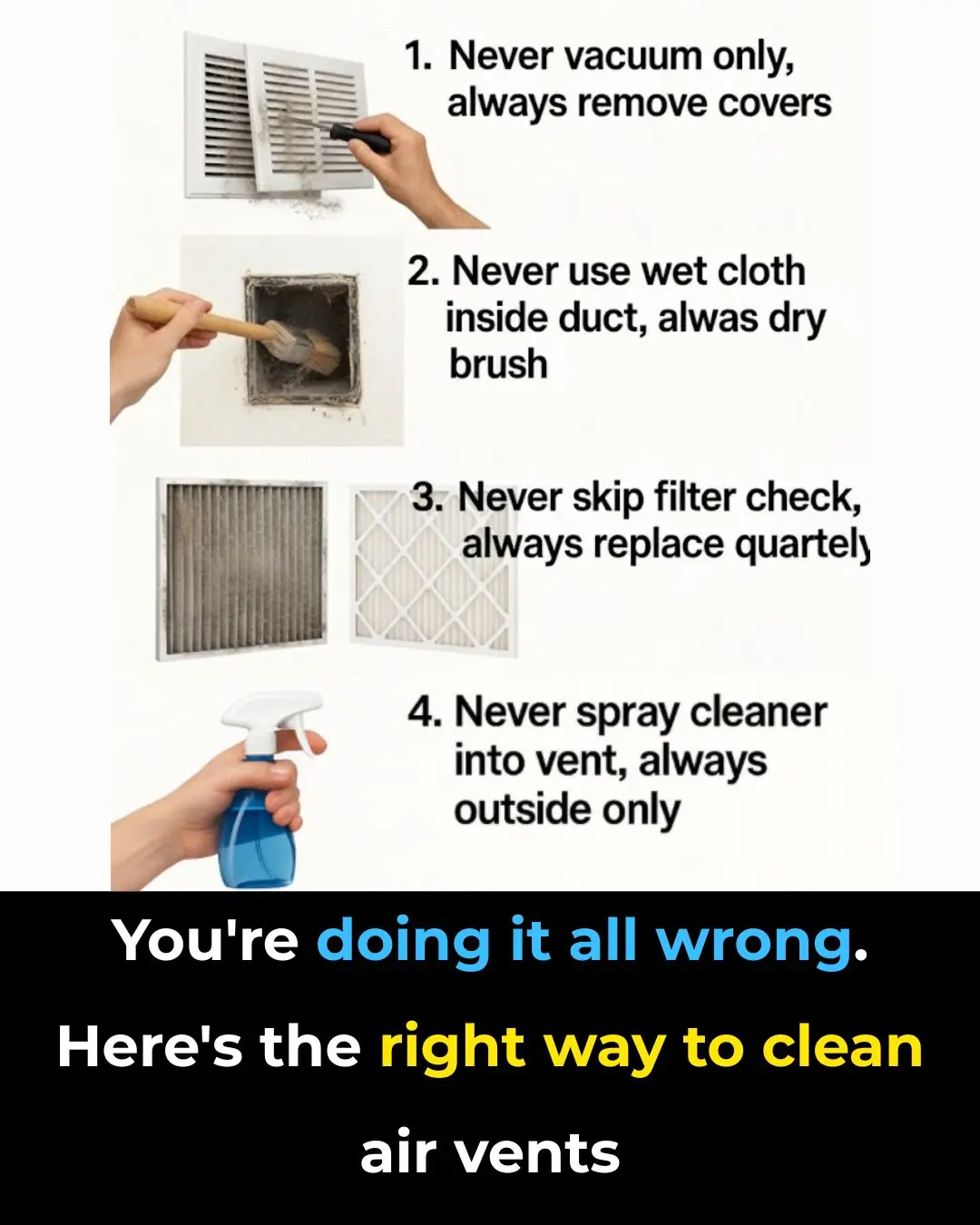

You’re doing it all wrong. Here’s the right way to clean air vents

Big Brother fans fume ‘she can't get away with this’ as they slam housemate

My nana taught me this hack to get rid of lawn burn from dog pee in 5 mins with 0 work. Here’s how it works

You're doing it all wrong. Here’s the right way to store milk and dairy

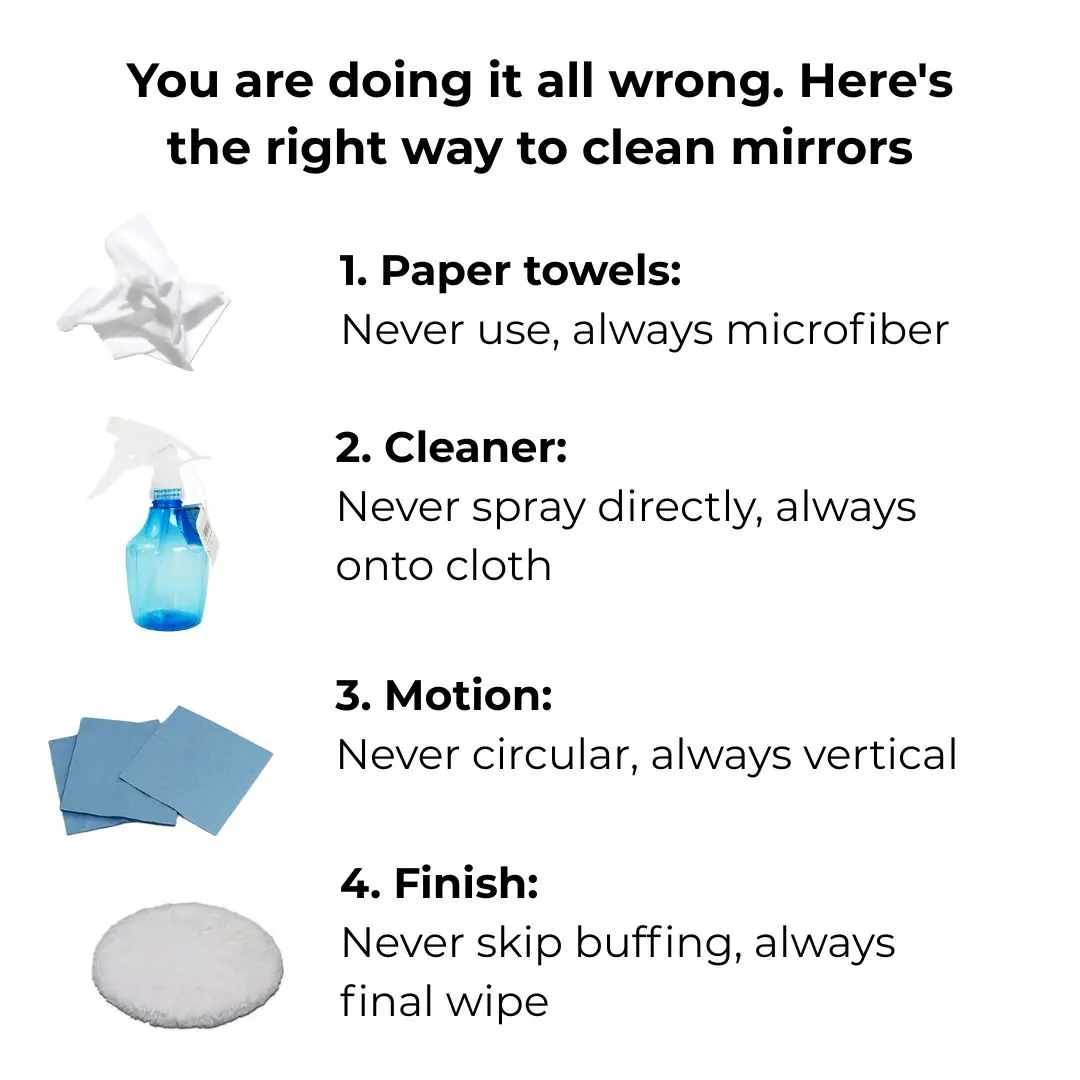

You are doing it all wrong. Here's the right way to clean mirrors

Most do this wrong. 10 leftovers you’re storing wrong

Delicious and crispy onion salt, you can keep it all year round without worrying about scum, just make it this way, whoever eats it will remember it forever

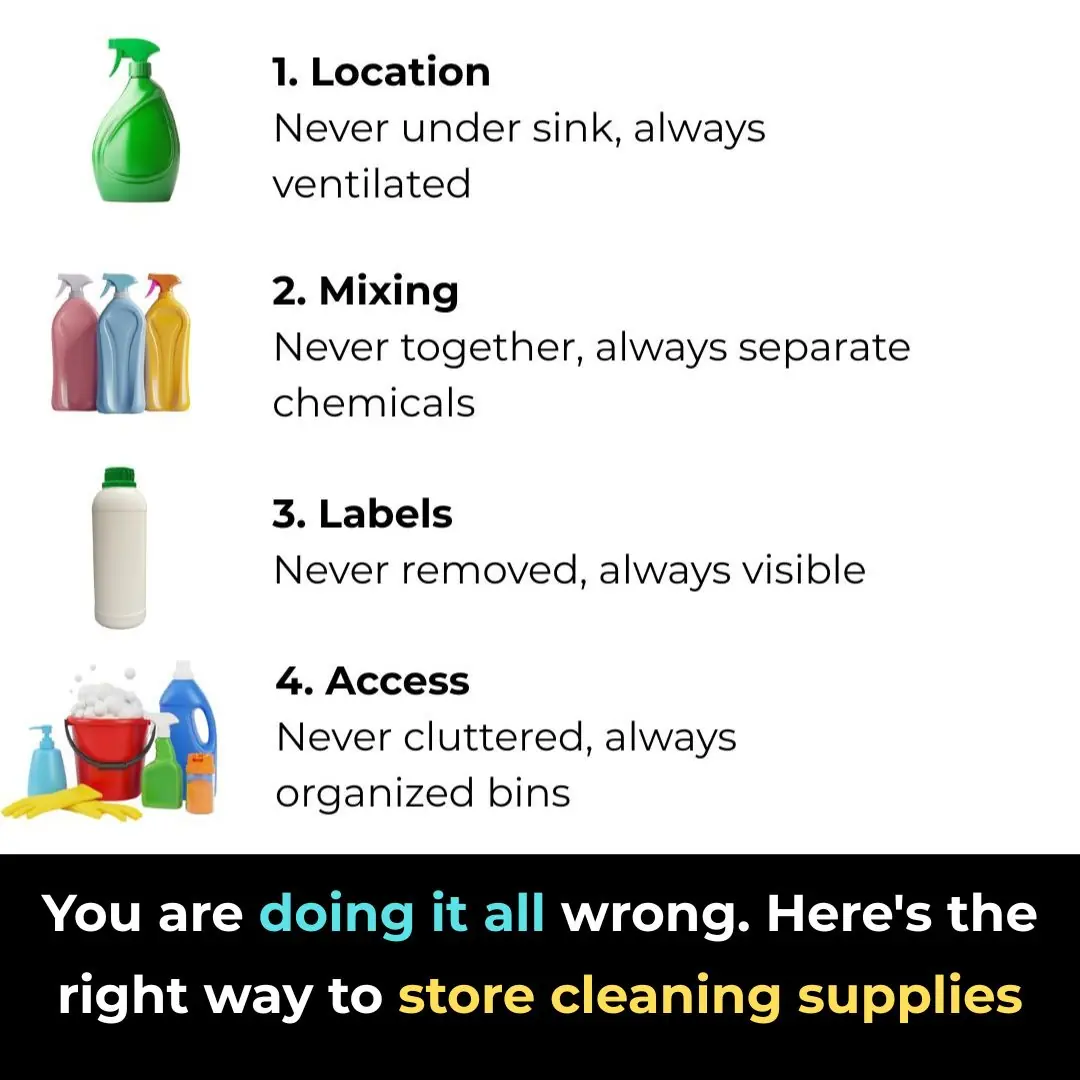

You are doing it all wrong. Here's the right way to store cleaning supplies

My nana taught me this hack to whiten yellow pillows in 5 mins with 0 work. Here’s how it works

3 ultimate recipes using Vaseline & lemon to erase dark spots, clear acne and glow skin

These Seeds Can Do Magic On Your Hair

12 Fruit Trees You Must Prune in August — and the Science Behind It

Achieve Glass Skin in Just 1 Week: Your Ultimate Guide to Radiant, Smooth, and Flawless Skin

Fermented Rice Water & Cloves Scalp Treatment

Easy Guide to Using Rice Water for Hair Growth: Natural Solutions for Stronger, Shinier, and Healthier Hair

10 DIY Beauty Ice Cubes for Glowing Skin, Acne, and Anti-Aging