Photographs reveal first glimpse of uncontacted Amazon community

Exclusive: Remote Cameras Capture Rare Images of Isolated Massaco People Thriving in Brazilian Rainforest

By John Reid and Daniel Biasetto

In partnership with O Globo

In the depths of the Brazilian Amazon, automatic cameras have captured never-before-seen images of the isolated Massaco people — a rarely glimpsed Indigenous group that appears to be not just surviving, but flourishing, despite growing environmental pressures from ranchers, loggers, and other encroaching interests.

The images, released by the Brazilian National Indigenous Peoples Foundation (Funai), show a group of naked Indigenous men deep in the forest, some carrying tools. They were recorded on February 17, 2024, as they approached a location where Funai periodically leaves machetes and axes. These metal tools are intentionally left to discourage uncontacted tribes from venturing into logging camps or settlements in search of such implements — a situation that has historically ended in deadly encounters.

This latest footage offers a clearer picture of a community that remains largely unknown to the outside world. Named “Massaco” after the river running through their territory, the people’s actual name, language, and cultural practices remain a mystery. Still, the photographs suggest a group that is not only persisting but growing, with Funai estimating the population has at least doubled since the 1990s to around 200–250 individuals.

“Despite all the pressure from agribusiness and other extractive industries, the Massaco have shown remarkable resilience,” said Altair Algayer, a veteran Funai agent who has worked for more than 30 years to protect the group’s territory. “But there’s still so much we don’t know about them.”

Protecting Without Contact

Brazil pioneered the policy of no-contact with uncontacted Indigenous peoples in 1987, a move prompted by decades of fatal first-contact efforts that decimated tribes — often through the introduction of deadly diseases. Since then, countries like Peru, Colombia, Ecuador, and Bolivia have adopted similar policies aimed at preserving the autonomy and safety of these communities.

Funai’s approach involves indirect monitoring, satellite tracking, and the occasional placement of tools at specific drop points. These efforts have enabled researchers to learn about the Massaco’s semi-nomadic lifestyle, their use of massive three-meter-long bows for hunting, and their seasonal relocation of villages within dense forest areas.

To protect themselves from outsiders, the Massaco reportedly plant thousands of camouflaged wooden spikes in the soil — sharp traps designed to puncture feet or vehicle tires. One such spike, nearly indistinguishable from the muddy ground it emerged from, was documented in a recent Funai photo.

“Now, with these high-resolution images, we can see physical similarities between the Massaco and the Sirionó people, who live across the Guaporé River in Bolivia,” Algayer noted. “But without direct contact, we cannot confirm any cultural or linguistic connection.”

Wider Trends Across the Amazon

Remarkably, the Massaco are not alone in their growth. Across the Amazon, some isolated Indigenous groups are experiencing population increases — a trend that defies global patterns of cultural and linguistic loss. A 2023 study in Nature revealed evidence of expanding Indigenous communities along Brazil’s borders with Peru and Venezuela, including larger cultivated areas and extended longhouses captured in satellite imagery.

Other groups, such as the nomadic Pardo River Kawahiva of Mato Grosso state, show signs of similar growth despite not planting crops or building permanent structures. According to Jair Candor, a long-time Funai field agent overseeing the Kawahiva territory, their numbers have increased from about 20 individuals in 1999 to around 35–40 today.

“It’s a sign that non-contact policies, despite their challenges, are having positive effects,” Candor said. “These communities can sustain themselves if left in peace.”

Threats Persist Despite Progress

Still, significant threats remain. Funai continues to operate with limited funding and a small, unarmed field team. Staff often face dangerous conditions, including direct threats from criminal groups. In 2022, Indigenous rights advocate Bruno Pereira and journalist Dom Phillips were murdered while documenting illegal activity in the Amazon.

The situation is further complicated by a lack of strong legal protections. According to a draft report from the International Working Group of Indigenous Peoples in Isolation and Initial Contact, Brazil has 61 confirmed isolated groups and 128 unverified reports. Yet, unlike Peru or Colombia, Brazil still lacks comprehensive legislation dedicated specifically to protecting uncontacted peoples.

“Brazil has led the way in developing best practices, but the legal framework is still incomplete,” said Antenor Vaz, a researcher who helped initiate the no-contact policy with the Massaco in 1988. “And the pressure from agribusiness, mining, and other industries is relentless.”

One of the tactics often used by land grabbers and illegal actors is to deny the very existence of these isolated groups, making it harder to enforce constitutional protections over Indigenous territories.

“The first thing invaders will say is: ‘No one lives there,’” explained Beto Marubo, a representative of the Union of Indigenous Peoples of the Javari Valley, which is home to 10 confirmed uncontacted communities — the highest number in the Amazon. “That’s why evidence like these photographs is so important.”

Indigenous-Led Protection and Hope

Neighboring Indigenous communities are also stepping in to protect their uncontacted relatives. Along the Brazil–Peru border, the Manchineri people are helping monitor vulnerable areas. In Rondônia, the Amondawa are doing the same, while the Guajajara in Maranhão have set up patrols to defend forest territories against invasion.

In 2021, leaders in the Javari Valley established an Indigenous-led patrol team that won the UN Equator Prize for its innovative forest protection work. The team is part of a broader movement emphasizing Indigenous leadership in environmental conservation and defense of cultural autonomy.

“These people have the right to live, to their land, and to their way of life,” said Paulo Moutinho, co-founder of the Institute for Environmental Research in the Amazon. “But respecting their rights is not just a matter of justice — it’s essential for the survival of the rainforest itself.”

Conclusion

The survival — and even flourishing — of the Massaco and other isolated groups is a powerful testament to their resilience and to the importance of policies that prioritize Indigenous autonomy. Yet their future depends on continued vigilance, international support, and the political will to resist the pressures of exploitation.

The images from February offer more than a rare glimpse of a hidden world; they are a reminder that deep within the rainforest, cultures are thriving that have much to teach the modern world — if we allow them the space and safety to endure.

This article is part of a collaborative investigation between The Guardian and O Globo, supported by a grant from the Ford Foundation. John Reid is co-author of Ever Green: Saving Big Forests to Save the Planet. Daniel Biasetto is content editor at O Globo.

News in the same category

Humanity Has Officially Found 6,000 Exoplanets, NASA Announces

There’s A 90% Chance of Black Hole Explosion in the Next Decade, Scientists Say

Prime views of the Andromeda Galaxy and Ceres—October 2

Northern Lights Could Be Seen in Northern U.S. — Sept 30 – Oct 1, 2025

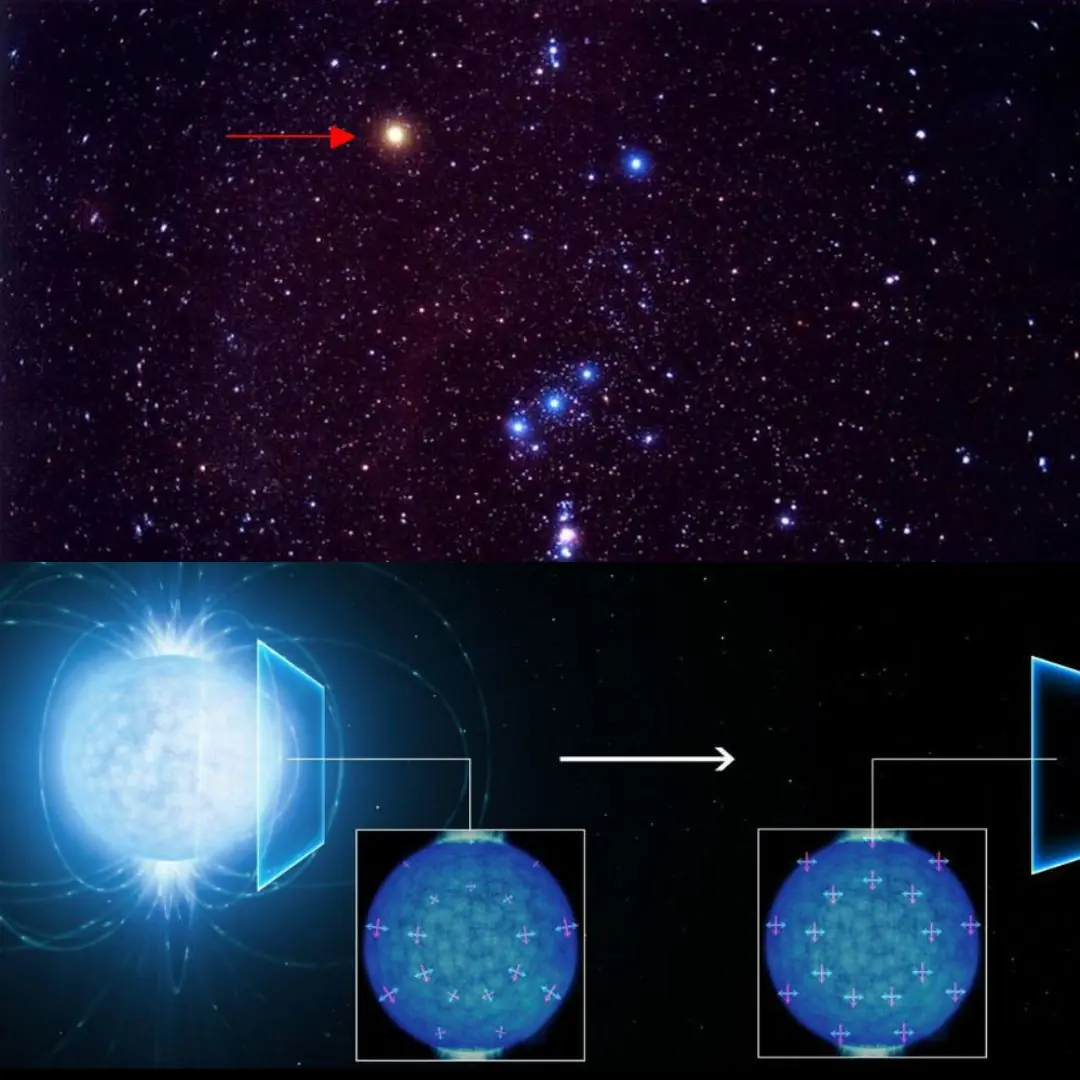

Alnitak, Alnilam, and Mintaka: Orion’s Belt Stars Thousands of Light-Years Away

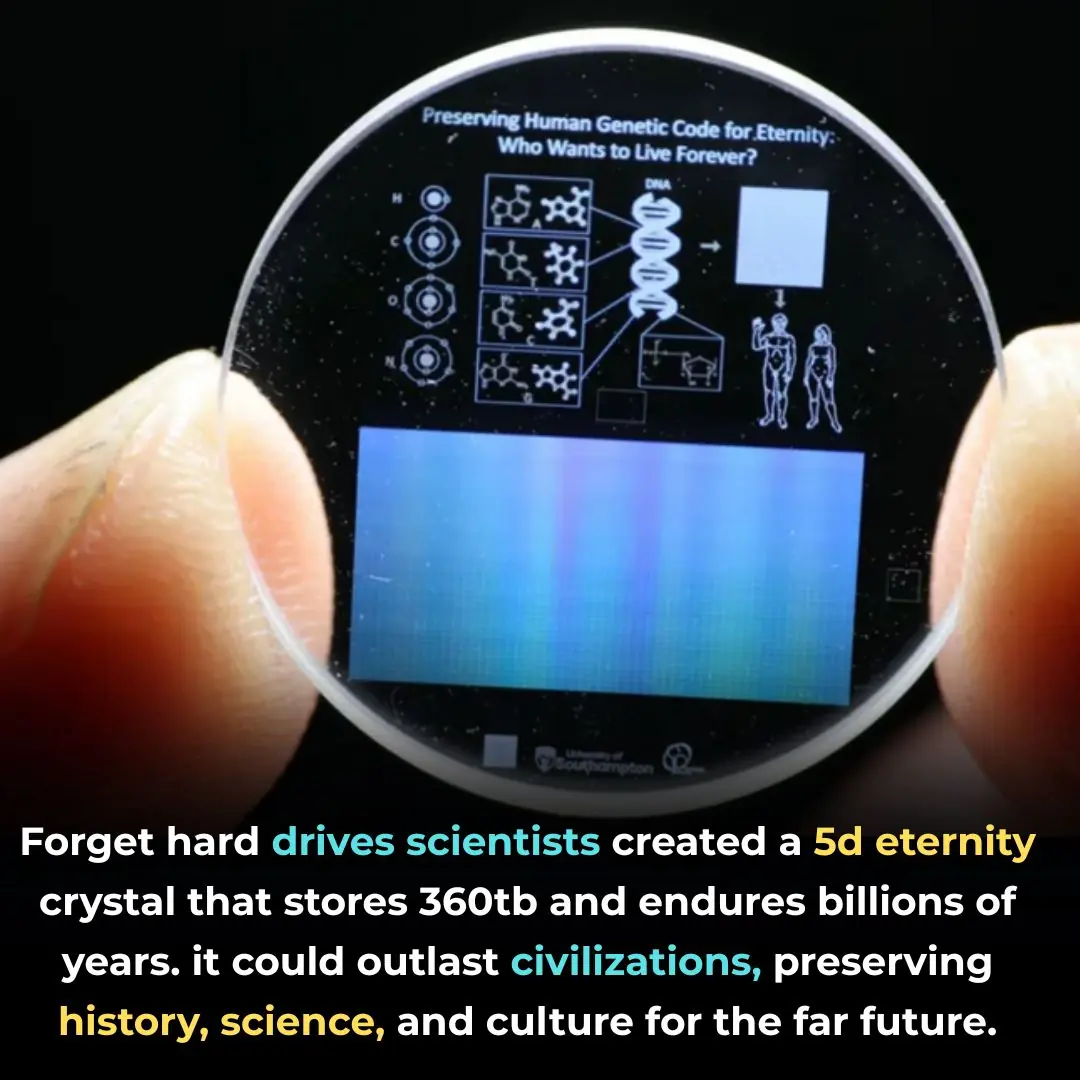

Humanity Preserved: A 5D Crystal Holds 360 TB of Our Genome to Outlast Civilization

Researchers make groundbreaking discovery about ChatGPT after testing it with 2,400 year-old math problem

Why this city has introduced a screen time limit of 2 hours per day

The Truth Behind the Bermuda Triangle May Be Scarier Than UFOs

Over 99% of peer-reviewed studies confirm climate change is real and driven by humans

Passenger lands in hospital after humiliating TSA spat over stubborn jewelry

A Man Knocked Down His Basement Wall, Discovering Ancient Underground City That Housed 20,000 People

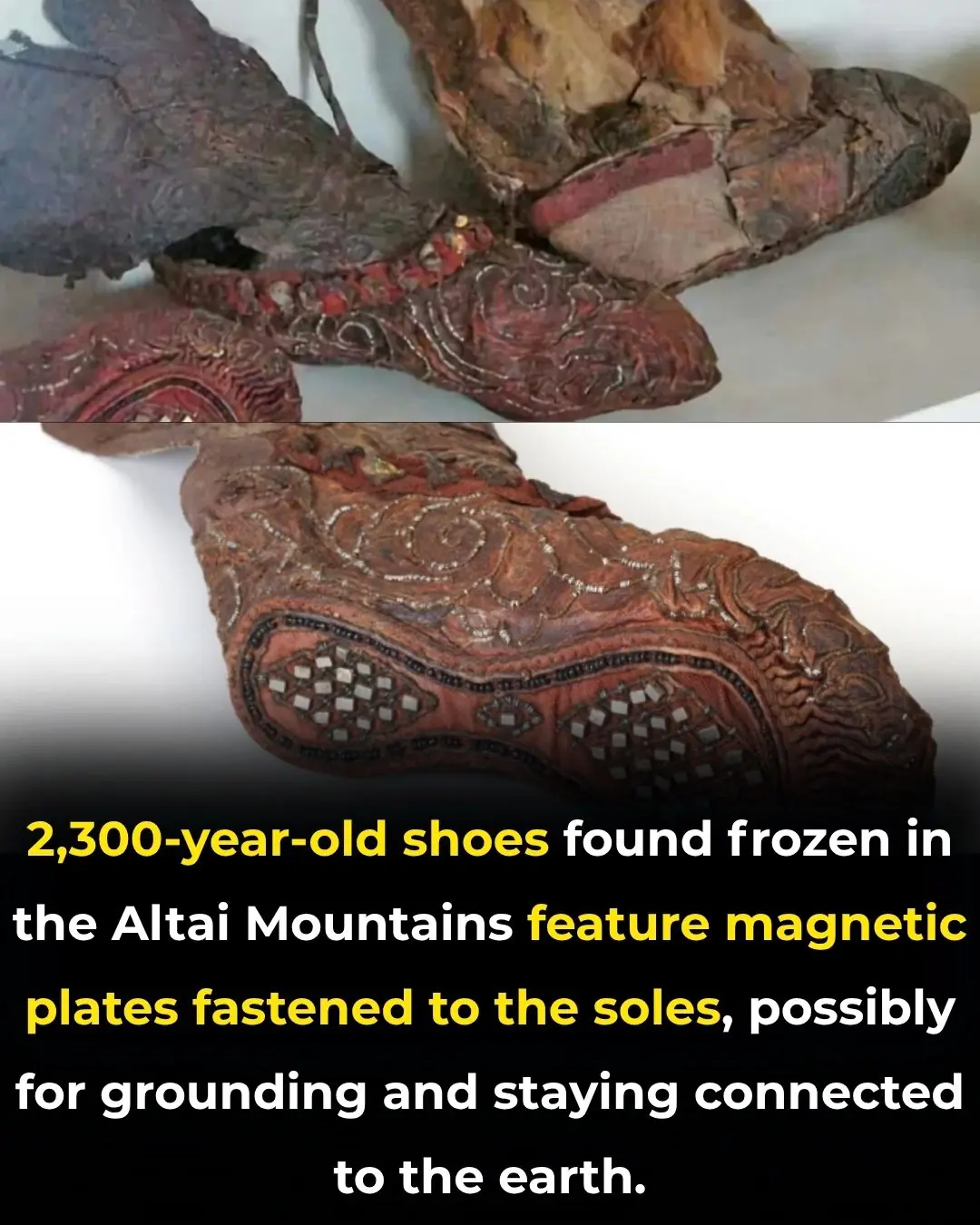

Magnificent 2300-Year-Old Scythian Woman’s Boot: A Timeless Fashion Statement

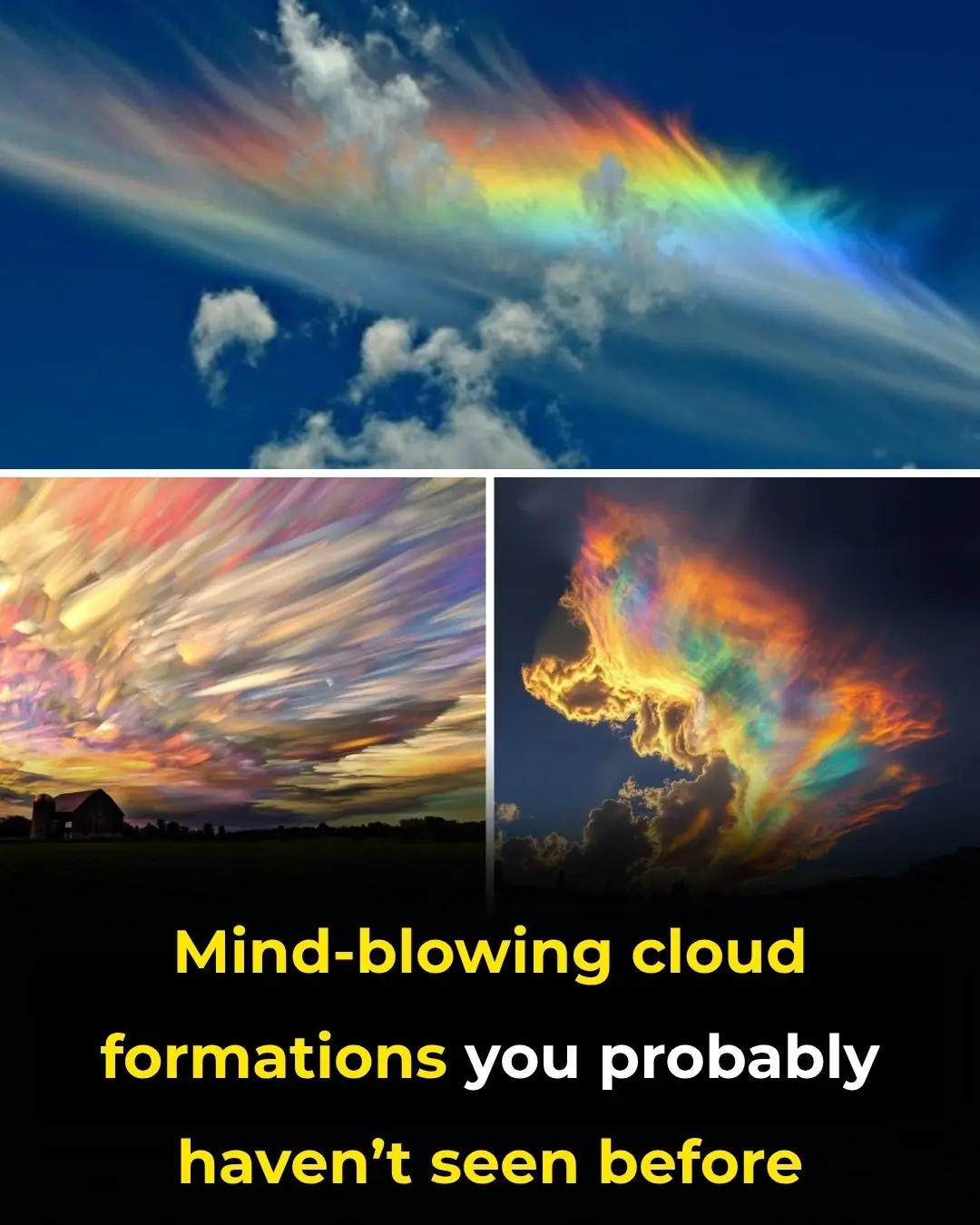

Mind-Blowing Cloud Formations You Probably Haven’t Seen Before

On the southern edge of the world, a waterfall runs red as blood

Rare reddish-orange snowy owl in Huron County captivates birdwatchers

Wildlife Crossings: A Vital Solution for Highway Safety and Biodiversity Conservation

Floating Gardens on Parking Lot Roofs: Japan’s Green Revolution

News Post

Aloe Vera and Cinnamon Remedy: Natural Benefits for Eye Health, Immunity, and Healing

12 Powerful Benefits of Moringa Seeds

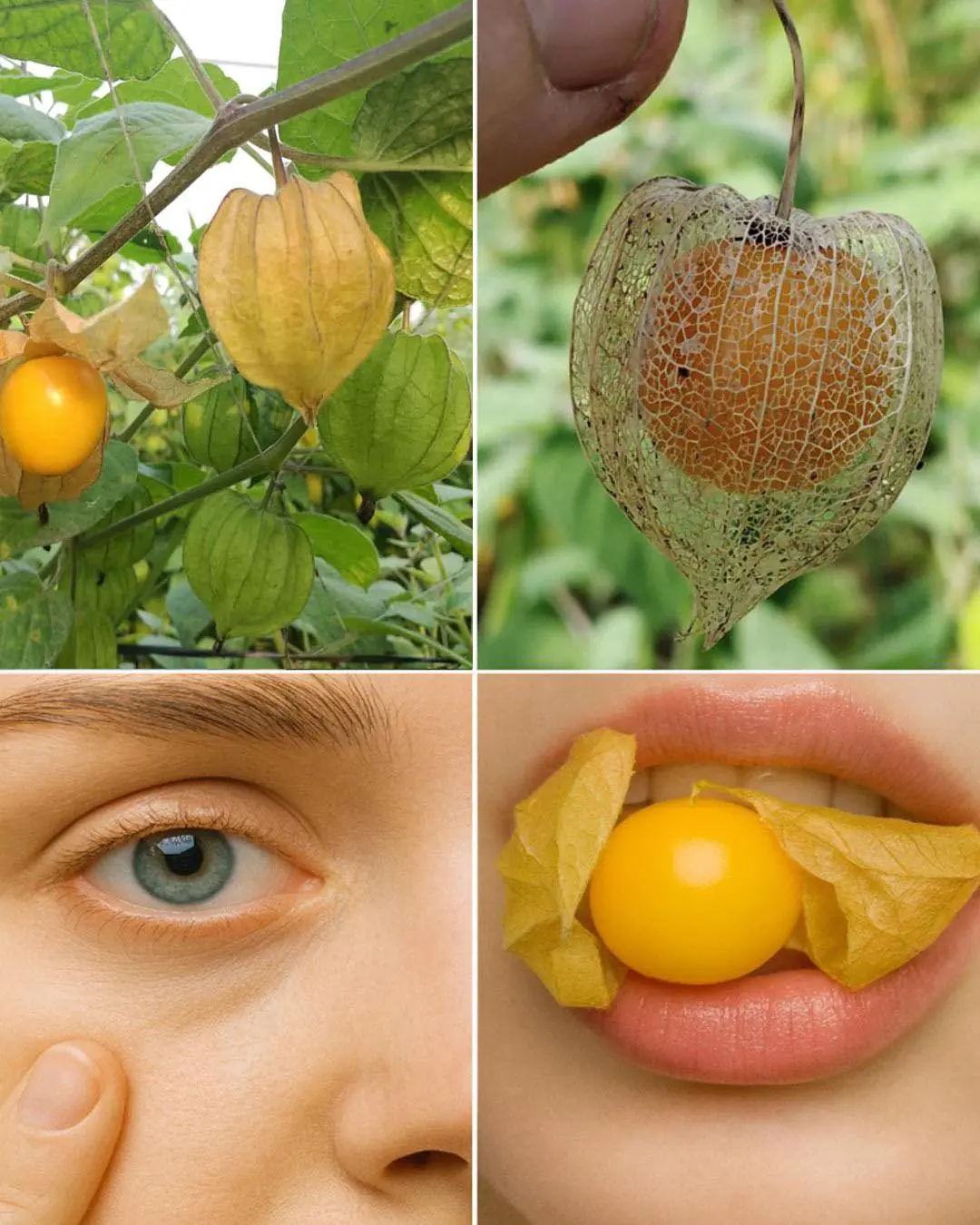

Goldenberries (Physalis peruviana): A Nutrient-Packed Powerhouse for Health and Vision

Oregano: The Golden Herb for Eye Health

Some of the Benefits of Castor Leaves and the Seed

10 Benefits and uses of purslane

Chanca Piedra (Stonebreaker): Benefits and Uses

Do you need to unplug the rice cooker after the rice is cooked: The surprising answer November 27, 2024

7 Benefits Of Papaya Seeds & How To Consume Them Correctly

Bougainvillea likes to 'eat' this the most, bury it at the base once and the flowers will bloom all over the branches

The elders say: "If you put these 3 things on top of the refrigerator, no matter how much wealth you have, it will all be gone." What are these 3 things?

Can rice left in a rice cooker overnight be eaten? Many people are surprised to know the answer.

After boiling the chicken, do not take it out immediately onto a plate. Do one more thing to make sure the chicken is crispy, the meat is firm, and the skin does not fall apart when cut.

Cut this fruit into small pieces and put it in the pot to boil the duck: The bad smell is gone, the meat is fragrant, soft and flavorful.

Warts on Hands: Causes and Effective Natural Treatments

Medicinal Health Benefits of Turmeric, Curcumin and Turmeric Tea Based on Science

4 ways to preserve green onions for a whole month without spoiling, fresh as new

The best way to lower blood pressure fast!

9 Habits You Need To Adopt Today To Stop Alzheimer’s or Dementia Before It Starts