Scientists create a universal kidney: it is compatible with all blood types

Medicine Takes a Major Step Forward with the Creation of a Universal Kidney

Modern medicine has once again achieved a remarkable breakthrough in the field of organ transplantation. For the first time, scientists have successfully created a universal kidney—an organ compatible with all blood types. This innovation could dramatically reduce long transplant waiting lists by eliminating one of the most significant barriers to organ donation: blood type compatibility.

One of the greatest challenges in organ transplantation has always been ensuring compatibility between donor and recipient. When an organ is not compatible, the recipient’s immune system can rapidly attack it, leading to life-threatening complications or immediate organ failure. As a result, many patients must wait years for a suitable match, even when donor organs are available.

That challenge may now be close to being solved. A team of Canadian researchers has developed specialized enzymes capable of converting a kidney with blood type A into one with blood type O—the universal blood type that can be accepted by recipients of any group. This achievement marks a significant milestone in transplant medicine.

The implications are particularly important for patients with blood type O, who make up more than half of kidney transplant waiting lists worldwide. These patients can only receive organs from donors of the same blood type, which significantly limits their chances. A universal kidney could greatly improve access and reduce waiting times for this vulnerable group.

Enzymes That Make Universal Compatibility Possible

The groundbreaking research was published in Nature Biomedical Engineering and details how scientists from the University of British Columbia (UBC) engineered enzymes that remove specific sugar molecules from the surface of blood vessels within the kidney. These sugars are responsible for defining blood type antigens. By “cutting” them away, the organ effectively becomes blood type O and can be safely transplanted into any recipient.

To test the viability and safety of this approach, researchers conducted a carefully controlled procedure that posed no risk to living patients. An enzymatically modified kidney was transplanted into a brain-dead patient with the consent of the family. Over a two-day observation period, the kidney functioned normally and showed no signs of hyperacute rejection—a severe immune response that can destroy an incompatible organ within minutes.

By the third day, some blood-type markers began to reappear, triggering a mild immune response. However, this reaction was far less severe than what is typically observed in incompatible transplants, and researchers noted early signs that the body was beginning to tolerate the organ.

A Hopeful Future for Transplant Patients

“This is the first time we have observed this process in a human model,” said Dr. Stephen Withers, Professor Emeritus of Chemistry at UBC and co-leader of the enzyme development. “It provides invaluable insight that will help us improve long-term outcomes.”

This achievement is the result of more than a decade of research. In the early 2010s, Dr. Withers and his colleague Dr. Jayachandran Kizhakkedathu began exploring ways to create universal donor blood by removing blood-type-defining sugars. Their work later expanded to organs, where these same sugars coat blood vessels and trigger immune rejection if mismatched.

Traditionally, overcoming blood type incompatibility requires days of intensive treatment to remove antibodies and suppress the recipient’s immune system, often relying on organs from living donors. The new enzymatic approach could instead allow organs from deceased donors—previously considered incompatible—to become universally usable, potentially saving thousands of lives each year.

Regulatory approval for clinical trials will require further research to address remaining challenges. The biotechnology company Avivo Biomedical is leading the next phase of development, aiming to apply these enzymes in both organ transplantation and transfusion medicine, including on-demand production of universal donor blood.

“This is what it looks like when years of basic science finally connect directly with patient care,” Dr. Withers concluded.

News in the same category

When a person keeps coming back to your mind: possible emotional and psychological reasons

A promising retinal implant could restore sight to blind patients

Scientists develop nanorobots that rebuild teeth without the need for dentists

Grip Strength and Brain Health: More Than Muscle

Bioprinted Windpipe: A Milestone in Regenerative Medicine

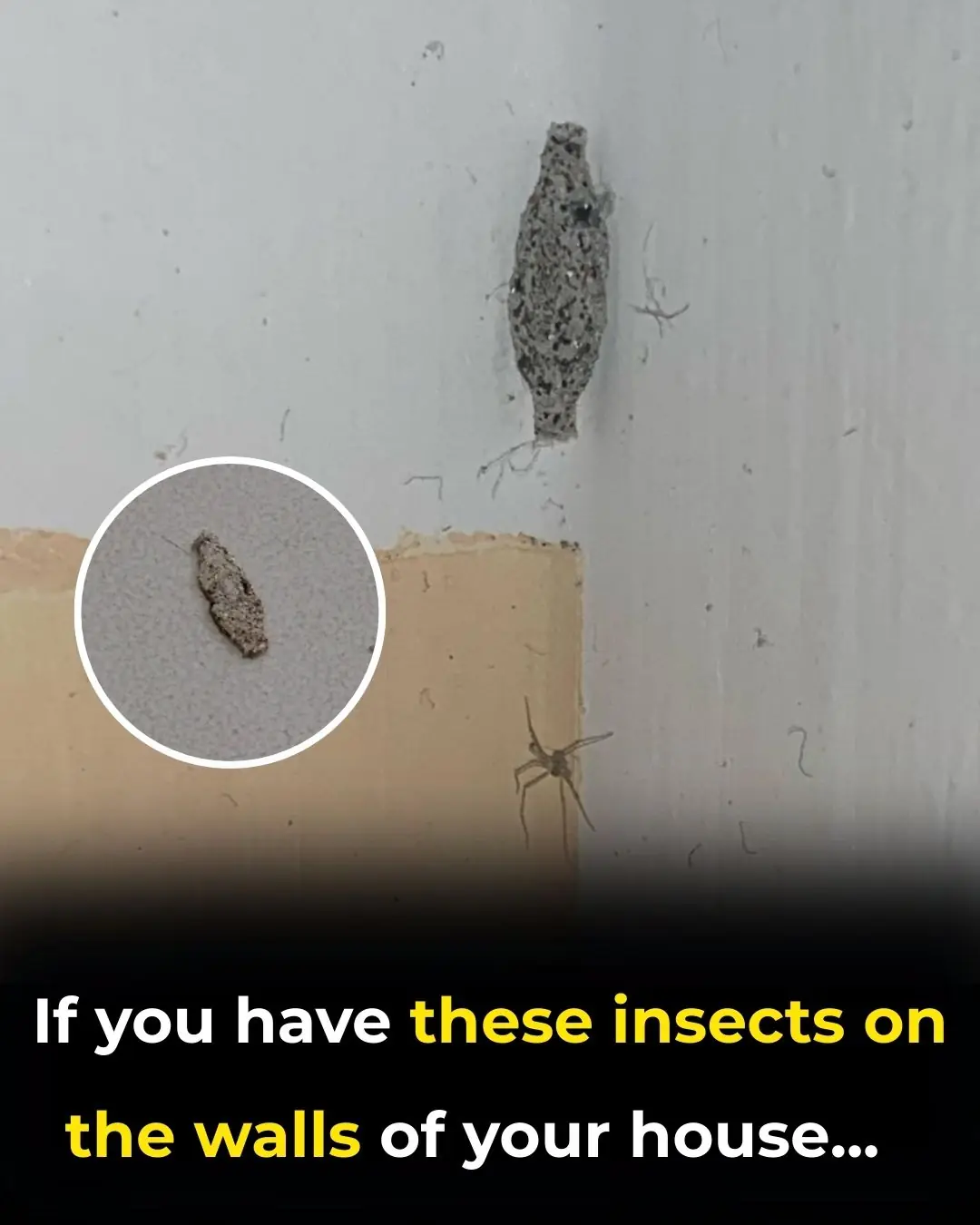

Bagworms Inside Your Home

Scientists discover that stem cells from wisdom teeth could help in regenerative medicine

What the Research Shows

Rethinking Flu Transmission: New Evidence Challenges Long-Held Assumptions

Nanobot Technology: A New Frontier in Cardiovascular Disease Treatment

Redefining Diabetes Treatment

If your partner says goodbye with a kiss on the forehead, be very careful: this is what it really means

Here’s what the letter ‘M’ and the crescent moon on the palm of your hand truly signify

How Helicobacter pylori Revolutionized the Understanding of Stomach Ulcers

New Research Raises Brain Health Concerns About a Common Sweetener

🌟 Breakthrough in Cancer Treatment: Targeted Light Therapy

HHS to Reexamine Cell Phone and 5G Radiation Risks Following Direction From RFK Jr

Injectable Gel for Nerve Regeneration: A Breakthrough in Healing

News Post

Just 1 Cup Before Bedtime: Sleep Deeper and Support Visceral Fat Loss Naturally

With just two cloves a day, you can prevent many diseases...👇 Write me a hello to let me know you're reading... I'll give you a health tip!

The Hidden Power of Guava Leaves: Why More People Are Drinking Them Daily 🍃

Doctors Are Impressed: Two Vegetables That Boost Collagen in the Knees and Relieve Joint Pain

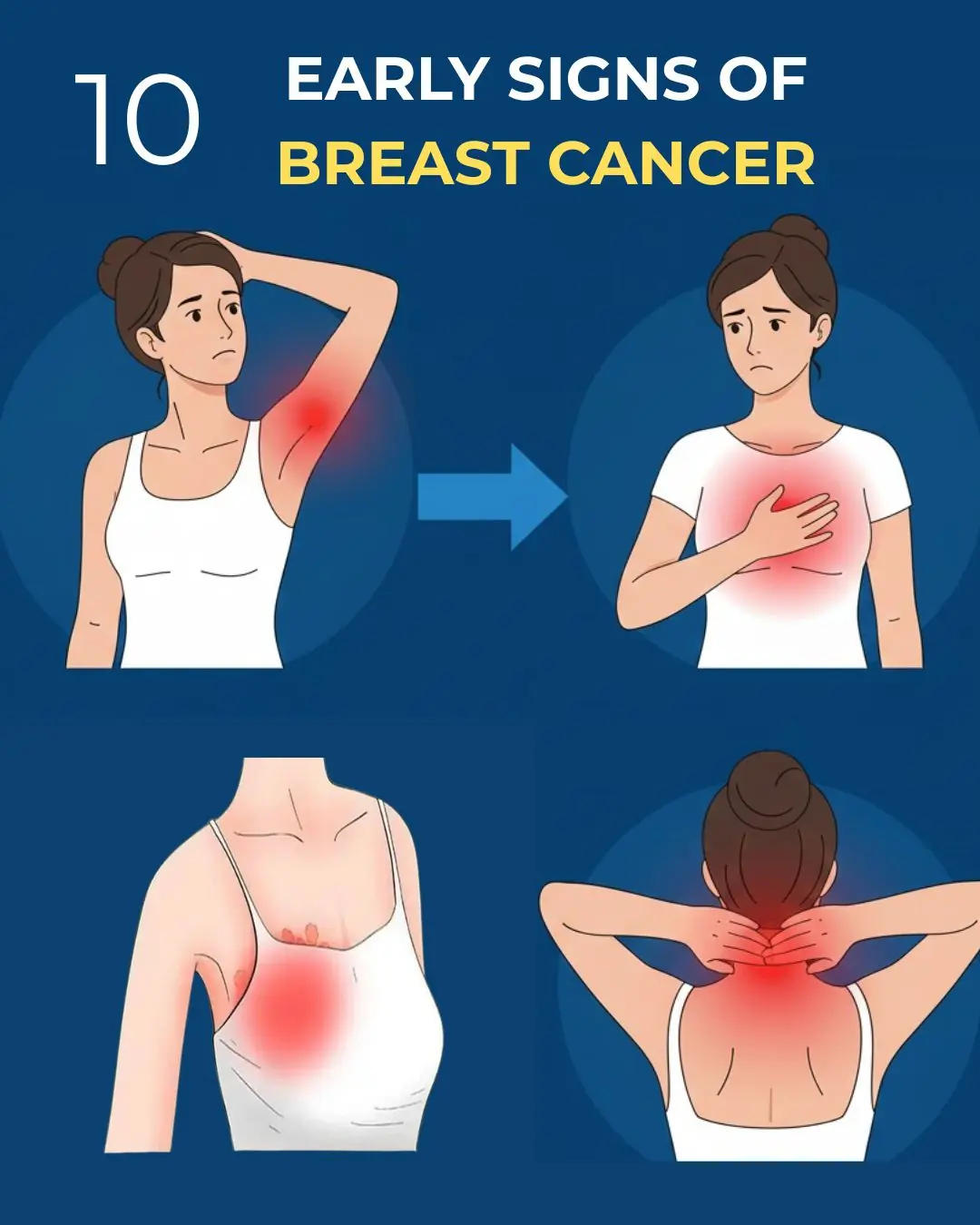

10 Warning Signs of Breast Cancer You Should Never Ignore

Avoid Infections with Your Partner by Adopting This Simple Habit

Freeze a Lemon, Grate It, and Add It to Your Food

Blending Cucumber and Pineapple May Support Digestive Health — But “Colon Detox” Claims Need Context

Breakthrough against osteoporosis: a mechanism identified that could reverse and regenerate damaged bones

This is how stomach cancer is detected: symptoms and warning signs that appear when eating and that you shouldn't ignore

4 surprising uses of egg boiling water.

Karen Tried to Sneak Into Business Class — Flight Attendant Made Her Walk Back in Front of Everyone.

Natural Drink That Can Transform Your Health: Cinnamon, Bay Leaves, Ginger, and Cloves

Discover Chayote: The Humble Squash That Naturally Transforms Your Health

Christmas Nightmare: Racist Flight Attendant Tries to Frame a Pilot, Ends Up in Handcuffs After One Secret Call!

His Final Wish Was to See His Dog—What the German Shepherd Did Stunned Everyone in the Yard

She Collapsed in the Ballroom—And the Duke’s Kindness Changed Her Fate Forever

The Photograph That Haunts the Internet: A Mystery Science Still Cannot Fully Explain

Abandoned to Die in the Snow: How a Lone Lumberjack Saved the Woman a Town Condemned