The Babylonians discovered the Pythagorean Theorem 1,000 years before Pythagoras

The vast majority of us—if not absolutely everyone—have heard of the great Greek mathematician and philosopher Pythagoras. He is widely regarded as one of the earliest figures in the history of pure mathematics and as a thinker whose ideas influenced generations of mathematicians and philosophers who followed him.

From our earliest years in school, we are taught that Pythagoras is best known for discovering the Pythagorean Theorem. This fundamental principle of geometry states that in any right-angled triangle, the square of the length of the hypotenuse is equal to the sum of the squares of the lengths of the other two sides.

The Pythagorean Theorem is commonly expressed with the formula:

a² + b² = c².

This equation is not merely an abstract mathematical idea; it has countless real-world applications. It is used to calculate inaccessible distances, plays a critical role in architectural design and construction, supports navigation and map-making, and helps solve a wide range of practical and theoretical problems across science and engineering.

But what if it turns out that this theorem existed long before Pythagoras himself?

Archaeologists have discovered a Babylonian clay tablet on which this mathematical relationship appears to be explained—one that predates Pythagoras by nearly 1,000 years. The tablet, known as IM 67118, is currently housed in the Iraq Museum. It was uncovered in 1962 at Tell edh-Dhiba’i, an ancient Babylonian settlement near present-day Baghdad.

This clay tablet, likely used for teaching purposes, dates back to around 1770 BCE, centuries before Pythagoras was born in approximately 570 BCE. Originating from the Old Babylonian period, it contains mathematical content related to geometric–algebraic theory, particularly involving right triangles, in a manner strikingly similar to later Euclidean geometry.

According to mathematician Bruce Ratner, who discussed this artifact in an article published by Springer, “The conclusion is unavoidable. The Babylonians knew the relationship between the length of the diagonal of a square and its side: d = √2.” Ratner further explains that this was likely the first number known to be irrational. This knowledge strongly suggests that the Babylonians were familiar with the Pythagorean Theorem—or at least with its special case involving the diagonal of a square, expressed as d² = a² + a² = 2a²—more than a millennium before the great sage whose name the theorem bears.

Given this evidence, an important question arises: why is the discovery still attributed to Pythagoras?

In reality, there are no surviving written records directly authored by Pythagoras himself that prove he discovered the theorem. His teachings were passed down orally within the Pythagorean school in Magna Graecia and preserved by members of the Pythagorean brotherhood. Over time, these ideas endured through tradition rather than documentation, ultimately becoming inseparable from Pythagoras’s legacy.

As a result, while the mathematical knowledge may have existed long before him, history has immortalized Pythagoras as the figure most closely associated with this timeless theorem—demonstrating how influence, transmission, and legacy can shape our understanding of discovery just as much as invention itself.

News in the same category

What Does “Durex” Actually Stand For

The reason might surprise you... Read more

What the First Animal You See Reveals About Your Hidden Flaw

Dreaming of a deceased person: here's what it means

The Common Bra Mistake

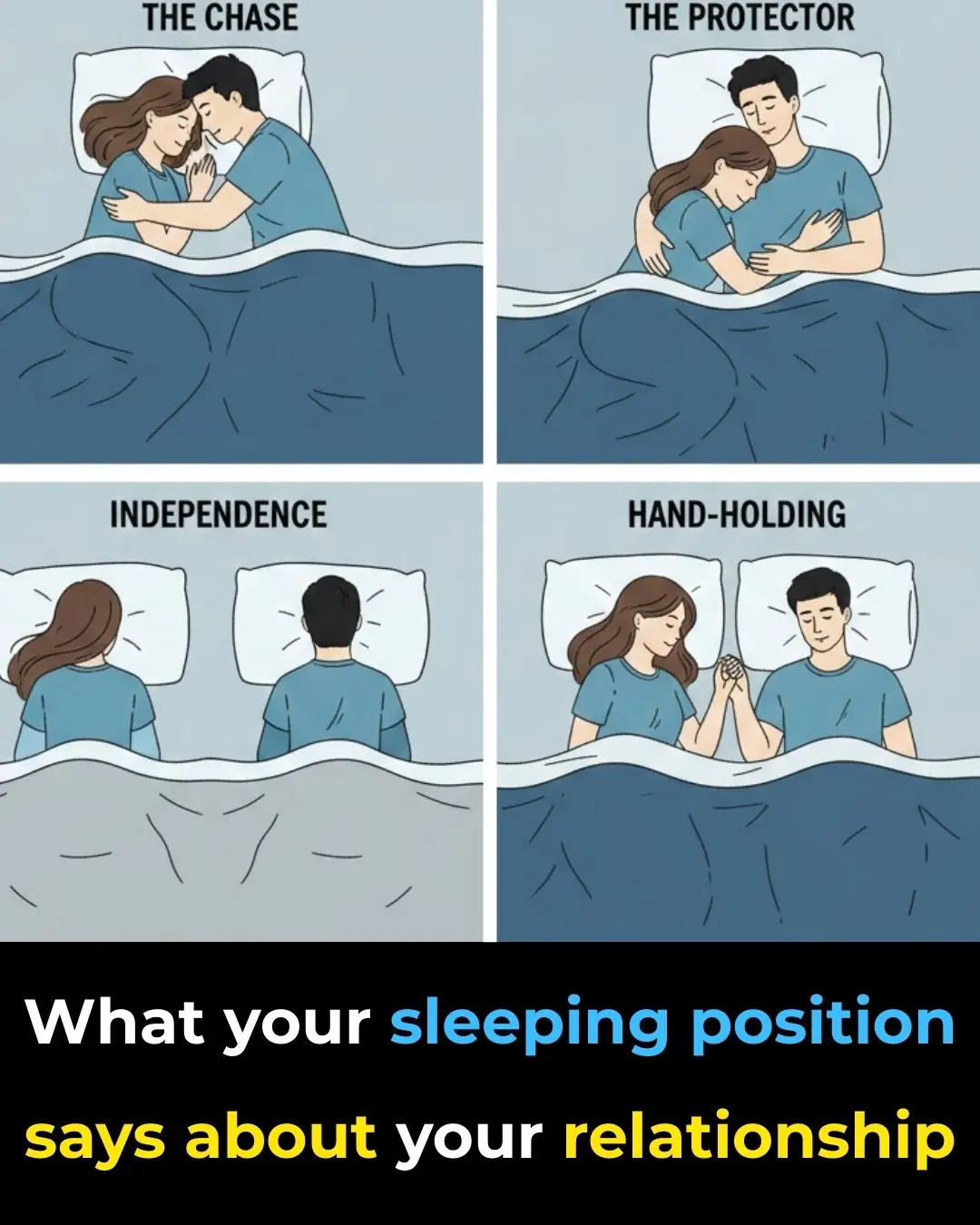

What Your Sleeping Position as a Couple Might Reveal

Envy Rarely Looks Like Hate

Why Slugs Keep Showing Up in Your Home

Almost Everyone Experiences This After Turning 70, Like It or Not

Did you know that if a white and yellow cat approaches you, it's because…

A baby is born in the United States from an embryo frozen more than 30 years ago.

12 nasty habits in old age that everyone notices, but no one dares to tell you

Why do couples sleep separately after age 50?

Scientists create a universal kidney: it is compatible with all blood types

When a person keeps coming back to your mind: possible emotional and psychological reasons

A promising retinal implant could restore sight to blind patients

Scientists develop nanorobots that rebuild teeth without the need for dentists

Grip Strength and Brain Health: More Than Muscle

Bioprinted Windpipe: A Milestone in Regenerative Medicine

News Post

They Thought It Was Just a Joke in the Gym. That Single Throw Changed Everything

The Bride Ripped Her Dress—So the “Nobody” Bridesmaid Stopped the Wedding Cold

He Accused Him of Stealing a Porsche—Then Dumped Wine on Him at a Pool Party. Five Minutes Later, the Real Owner Spoke.

She Publicly Shamed a “Man With Dark Glasses” at a Charity Gala—Then the Room Froze When He Spoke

Pancreatic Cancer: 10 Early Warning Signs You Should Never Ignore

Have you also developed these skin bumps on your neck?

What Your Urine Color Is Trying to Tell You

Why Your Pet “Steals” Your Spot

Noticing Red Veins on Your Thighs

Health Benefits of Thyme and Thyme Tea

Senior Boy Slaps Quiet Girl at Prom—Her Limo Driver Had Other Plans

The Hospital Bill

The Old Jacket

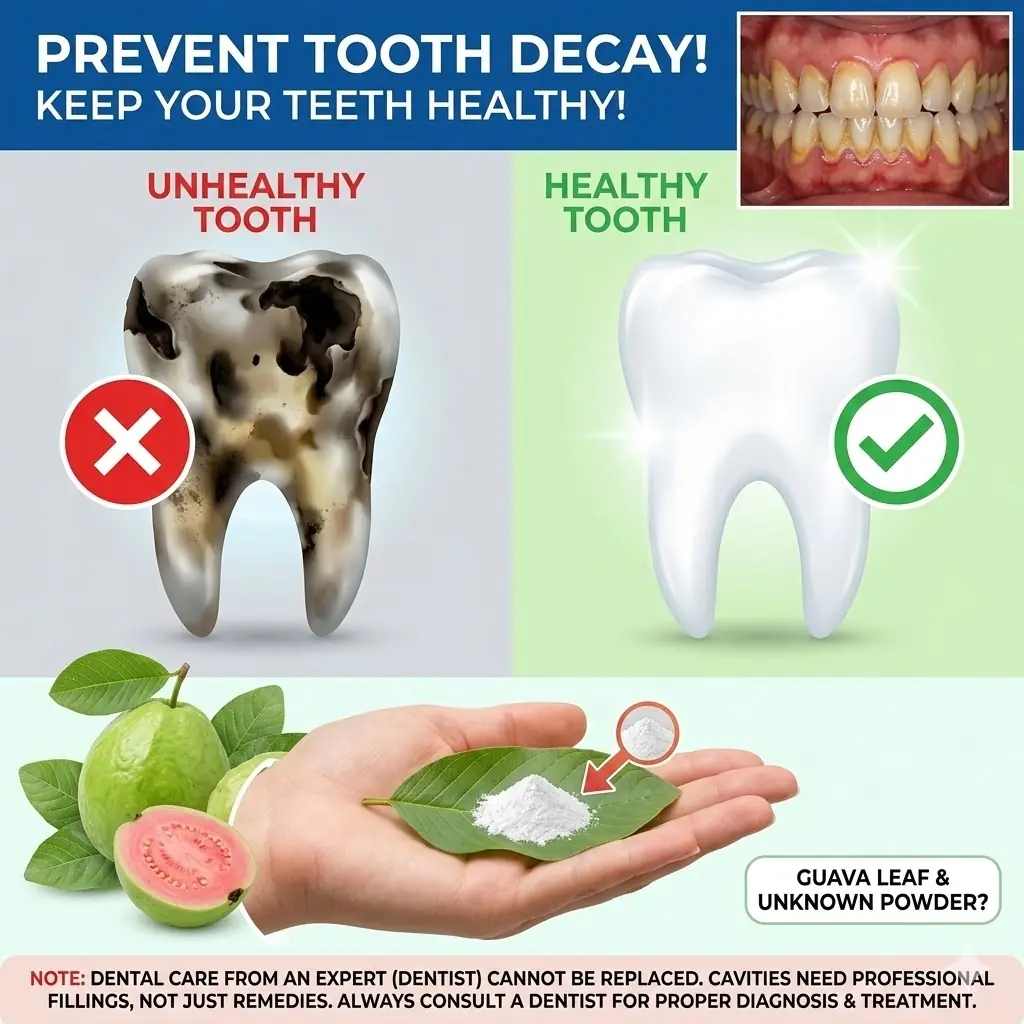

Discover Nature’s Secret: 3 Gentle Guava Leaf Remedies to Support Tooth Care Naturally

Discover Chayote: The Simple Squash That Naturally Supports Everyday Wellness

Men’s Vitality Booster: A Bold, Natural Ginger & Pineapple Health Shot

The Unexpected Duo for Healthier-Looking Hair Growth: Onion & Garlic Revealed

Discover Why Dandelion Root Is One of Nature’s Best-Kept Wellness Secrets

Mango, Guava, and Soursop Leaf Tea: Ancient Healing for Modern Wellness