Hattie McDaniel: Everything You Need To Know About The First Black Oscar Winner

Honoring 70 Years Since Her Passing: The Legacy of Hattie McDaniel

Hattie McDaniel’s life remains one of the most compelling and complicated stories in American entertainment history. Born on June 10, 1893, McDaniel came from humble beginnings, as noted by Biography.com (Biography.com). She began her artistic journey performing in traveling vaudeville shows across the United States. By the 1920s, she had carved out space for herself in a segregated entertainment landscape, making history as one of the first Black performers featured on The Golden West, a popular radio program of the era. In 1940, she shattered yet another barrier, becoming the first Black person to win an Academy Award for her unforgettable performance as Mammy in Gone With the Wind.

Despite her extraordinary talent and groundbreaking achievements, McDaniel received criticism throughout her career. Many objected to the limited, stereotypical roles she was offered, while she also faced exclusion and racism from the broader film industry. At the same time, she was attacked by some Black leaders who disapproved of the roles she portrayed. According to The New York Times, McDaniel spent much of her life caught between the constraints of Hollywood and the expectations of the Black community (The New York Times).

Yet she persevered. McDaniel continued pushing forward with dignity, using her platform to inspire younger Black performers and working tirelessly to help open doors in a notoriously discriminatory industry. Her complicated legacy sparked essential conversations about representation, opportunity, and the systemic barriers Black actors faced for decades.

In 2021, the Global Genesis Group announced plans for a biopic chronicling her extraordinary life, starring actress Raven Goodwin. “Individuals such as Hattie McDaniel were trailblazers in their struggle for equality, and their stories need to be told,” said Rick Romano, the company’s president, emphasizing the importance of bringing McDaniel’s experiences to a new generation (Global Genesis Group). Goodwin added that portraying McDaniel is an honor, a chance to highlight a life filled with both triumphs and challenges.

To understand the full scope of Hattie McDaniel’s influence, here are key facts about the first Black Oscar winner—compiled from Vanity Fair and other historical sources (Vanity Fair):

She was the daughter of formerly enslaved parents.

McDaniel was the youngest of thirteen children born to Henry and Susan McDaniel. Both of her parents had been enslaved before the Civil War. Her father later served in the 12th U.S. Colored Infantry Regiment and fought in the 1864 Battle of Nashville. Their stories of resilience helped shape Hattie’s own determination and work ethic (History.com).

She grew up in a family of performers in Denver, Colorado.

Although the McDaniel family struggled financially—her father spent decades seeking military support from the U.S. government—Hattie found early comfort in music. She sang in the church choir and performed so often that, according to her own recollections, her mother would sometimes give her a nickel just to quiet her down.

When the family moved to Denver, the McDaniel children became pioneers of the city’s Black entertainment scene. They produced plays and variety shows for their community, laying the foundation for Hattie’s lifelong passion for performing.

She began her career in minstrel shows.

In 1914, Hattie and her sister Etta founded the McDaniel Sisters Company, producing an all-women minstrel show. Hattie developed a humorous “Mammy” character—a satire of exaggerated racial stereotypes circulated at the time. While minstrel shows were problematic by nature, scholars note that many Black performers used the medium to mock or subvert racist caricatures (Smithsonian Magazine).

She established herself as a blues singer.

During the 1920s, McDaniel pivoted to blues performance, branding herself as “The Old Pep Machine” and “The Sepia Sophie Tucker.” She toured the Black vaudeville circuit, recording tracks such as “Boo Hoo Blues” and “Dentist Chair Blues.” Her stage presence and booming voice made her a regional star.

Early success didn’t protect her from hardship.

Despite her growing reputation, McDaniel still struggled financially. After losing her job as a chorus member during Show Boat because of the 1929 stock market crash, she became stranded in Milwaukee. She worked as a restroom attendant at a nightclub until one night she was invited to sing. Her rendition of “St. Louis Blues” captivated the audience, securing her a two-year headline run—until the club closed during the Great Depression. With only $20 to her name, she boarded a bus for Hollywood.

She became Hollywood’s go-to actress for maid or “Mammy” roles.

By the early 1930s, McDaniel was regularly cast as a maid in films. The roles were limited and steeped in stereotypes, but McDaniel approached them with complexity and professionalism. She famously said, “I can be a maid for $7 a week, or I can play a maid for $700 a week.” According to NPR, McDaniel viewed her work as a doorway—one she hoped would eventually lead to better opportunities for Black actors (NPR).

Her performance in Gone With the Wind changed everything.

McDaniel earned her breakthrough role thanks to her brother, Sam McDaniel, who was also a working actor. Bing Crosby recommended her to producer David O. Selznick, praising “the actress who played Queenie in Show Boat”—unaware of her name. Selznick listened.

In 1940, McDaniel became the first Black person to win an Academy Award. Although she was barred from attending the film’s premiere due to segregation, her Oscar win was celebrated as a historic milestone. In her emotional acceptance speech, delivered at the Cocoanut Grove, she said, “I sincerely hope that I shall always be a credit to my race and the motion picture industry.”

She clashed with NAACP leader Walter White for years.

Walter White, then head of the NAACP, openly criticized McDaniel, Stepin Fetchit, and Louise Beavers for accepting roles he believed reinforced racist stereotypes. McDaniel defended herself repeatedly, emphasizing that she worked to create opportunities where none previously existed. Their disagreements became highly public and continued for years. She declined White’s 1946 invitation to a Hollywood summit, writing that she would not “break bread with Walter White,” whom she felt had insulted both her intelligence and her integrity.

She was an outspoken supporter of Black civil rights.

Despite the tension with national NAACP leadership, McDaniel worked closely with local NAACP chapters. She advocated for Black homeowners in Sugar Hill—known then as the “Black Beverly Hills”—where white residents attempted to enforce segregationist housing policies. McDaniel rallied more than 200 community members to attend court hearings, which ultimately led to a legal victory declaring such practices unconstitutional (The Guardian).

Her home also became a gathering place for artists like Duke Ellington, Paul Robeson, and Cab Calloway—luminaries who found comfort and community away from the pressures of white-dominated Hollywood.

She returned to radio work in the final years of her life.

In 1947, McDaniel assumed the title role on the CBS radio series Beulah, becoming the first Black woman to star in her own network radio program. Her health later deteriorated due to diabetes and breast cancer. She died on October 26, 1952, and was buried at Rosedale Cemetery. In 1999, a memorial honoring her legacy was installed at Hollywood Forever Cemetery, ensuring her contributions would never be forgotten.

Thank you, Hattie McDaniel — your legacy opened doors and changed history.

News in the same category

Beating Seasonal Depression: 8 Directories To Help You Find An Affordable Black Therapist

Hip-Hop Pioneer Rakim Launches New ‘Notes’ Fintech Platform to Empower Independent Artists

New ‘Eddie’ Documentary About Comedy Legend Eddie Murphy Is Coming to Netflix

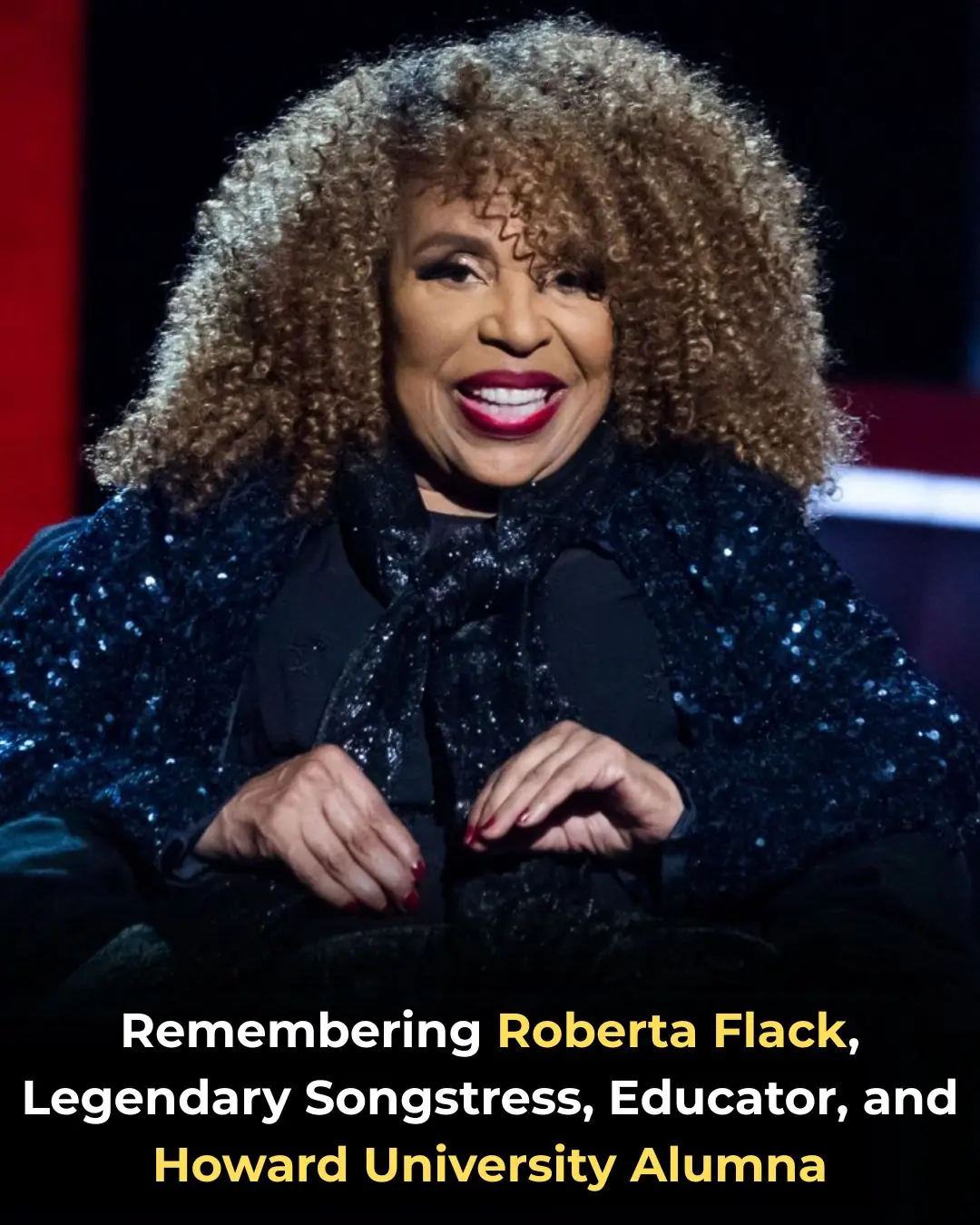

Remembering Roberta Flack, Legendary Songstress, Educator, and Howard University Alumna

New CBS Show ‘The Gates’ Marks Return of Predominantly Black Cast to Daytime Soaps for First Time in Three Decades

4 Inspiring Things You Never Learned About W.E.B. Du Bois

6 Inspiring Achievements That Black Women Accomplished First

Afrobeats Star Tems Joins San Diego FC Major League Soccer Ownership Group

Khaby Lame Becomes The Most-Followed Person On TikTok

40 Years Ago, Michael Jackson’s ‘Thriller’ Album Made History at the Grammys

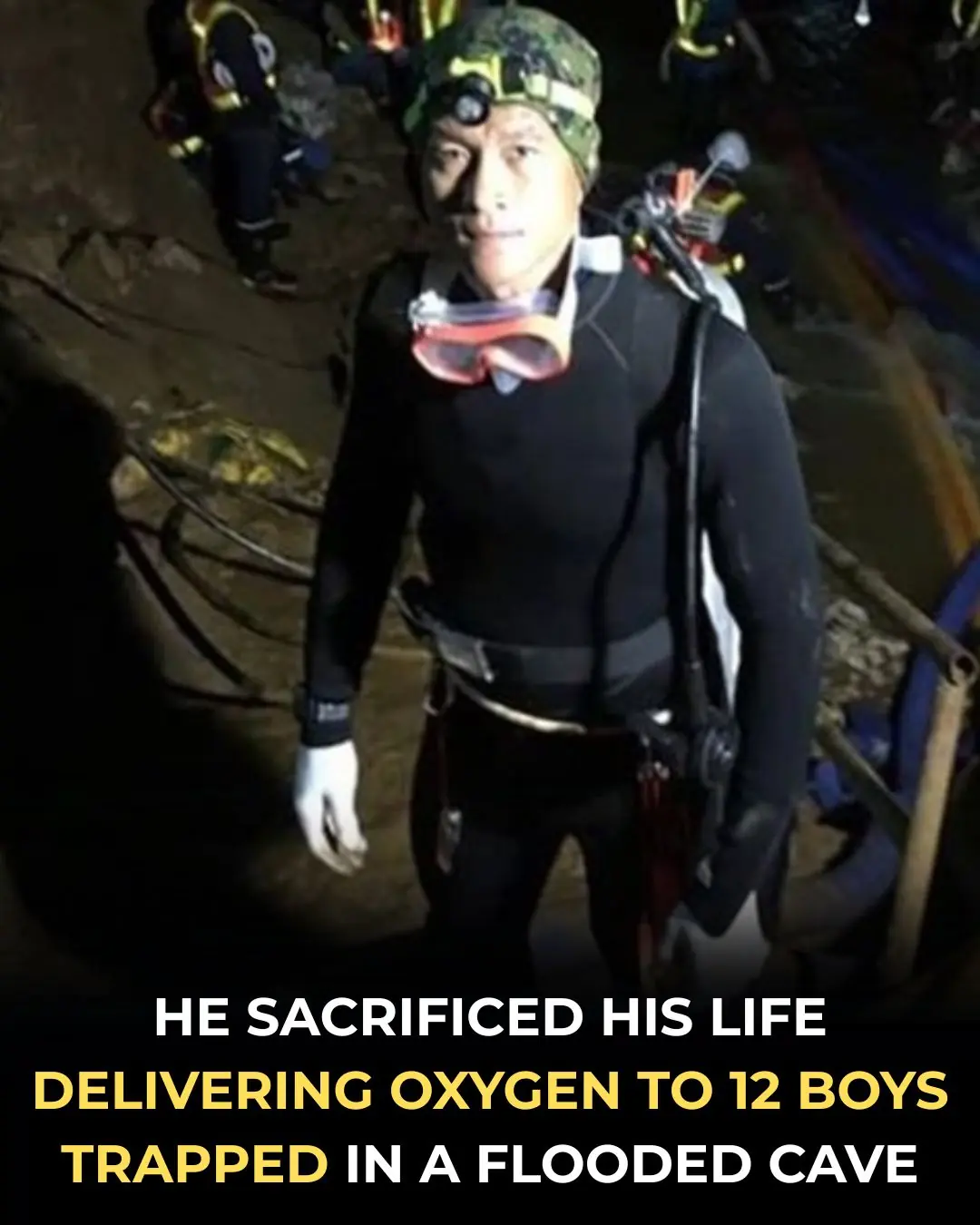

Remembering Saman Kunan: A Hero of Unwavering Courage

You’re Doing It All Wrong: Here’s the Right Way to Fertilize in Cold Weather

Most People Never Realize This: Why Your Basil Keeps Wilting — and the No-Fail Hack to Bring It Back to Life

These Are the 3 “Favorite Flavors” of Cancer Cells — If You Want to Stay Healthy, Eat Less of Them

Women Should Drink Perilla Leaf Water with Lemon at These 3 Times for Brighter Skin and a Slimmer Waist

Neat Hack

My Nana Taught Me This 2-Minute Hack for Lifting Carpet Stains With Zero Effort — Here’s How It Works

Don’t Overlook Those Trays at Goodwill — Here Are 10 Brilliant Ways to Reuse Them

News Post

How Two Quiet Hours a Day Can Rebuild Your Brain

Powerful Health Benefits of Pineapple You Should Know

Meet the First Woman Graduate From Howard University Law School, Charlotte E. Ray

Beating Seasonal Depression: 8 Directories To Help You Find An Affordable Black Therapist

Hip-Hop Pioneer Rakim Launches New ‘Notes’ Fintech Platform to Empower Independent Artists

New ‘Eddie’ Documentary About Comedy Legend Eddie Murphy Is Coming to Netflix

Remembering Roberta Flack, Legendary Songstress, Educator, and Howard University Alumna

New CBS Show ‘The Gates’ Marks Return of Predominantly Black Cast to Daytime Soaps for First Time in Three Decades

4 Inspiring Things You Never Learned About W.E.B. Du Bois

6 Inspiring Achievements That Black Women Accomplished First

Afrobeats Star Tems Joins San Diego FC Major League Soccer Ownership Group

Khaby Lame Becomes The Most-Followed Person On TikTok

40 Years Ago, Michael Jackson’s ‘Thriller’ Album Made History at the Grammys

Raspberry Leaf Power: 30 Benefits and How to Use It

7 Powerful Bay Leaf Benefits for Heart Health and Smoother Blood Flow

Stop Counting Calories — The “100g Protein Rule” That Boosts Energy and Crushes Cravings

How Cats Use Smell and Earth’s Magnetic Field to Navigate Home Over Long Distances

10 Supplement Combinations You Should Never Take Together