Hepatitis C Virus Detected in Brain Tissue: A Potential Link to Schizophrenia and Bipolar Disorder

A surprising scientific discovery may revolutionize how we think about severe psychiatric disorders. In a recent study, researchers detected traces of the Hepatitis C virus (HCV) in the choroid plexus — a brain structure that lines the fluid‑filled cavities in the brain — of individuals diagnosed with schizophrenia and bipolar disorder. This unexpected finding raises the possibility that viral infections might contribute directly to the development or course of some psychiatric illnesses, opening entirely new horizons for both research and treatment.

Traditionally, mental health conditions such as bipolar disorder and schizophrenia have been explained largely in terms of genetics and neurochemistry — chemical imbalances, neurotransmitter dysfunctions, and inherited vulnerability. However, the discovery of HCV in the choroid plexus suggests a different or additional mechanism: rather than infecting neurons directly, the virus may reside in the brain’s epithelial lining, influencing immune responses and gene expression in adjacent brain regions.

In the pivotal study, scientists used high-throughput sequencing on postmortem brain samples obtained from a brain biobank specializing in psychiatric disorders. They examined the choroid plexus from individuals with schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, and, for comparison, major depressive disorder, as well as from control subjects. They found that HCV RNA was specifically present in the choroid plexus of schizophrenia and bipolar subjects, but was not detected in unaffected controls — and notably absent from the hippocampus (a brain region important for memory).

To strengthen their case, the researchers also turned to a very large clinical database: the TriNetX electronic health records system, covering some 285 million patients. From that data, they observed that 3.6% of people with schizophrenia and 3.9% of people with bipolar disorder had chronic HCV, far above the rate seen in control populations (about 0.5%) and individuals with major depressive disorder (1.8%) — pointing toward a possible disease‑related association rather than mere co‑incidence or risky behaviors like intravenous drug use.

What's more, even though viral RNA was not found in the hippocampus itself, its presence in the choroid plexus correlated with changes in gene expression in the hippocampus. These changes included activation of innate immune pathways, suggesting that viral infection in the barrier tissue could influence deeper brain structures indirectly.

These insights could have profound implications for treatment. If a subset of psychiatric patients carry HCV in their brain lining, then antiviral therapies might help — not just for their liver disease, but potentially to reduce or ameliorate psychiatric symptoms. Indeed, the researchers themselves propose screening for HCV in patients with schizophrenia and bipolar disorder, to investigate whether treatment of the virus can bring psychiatric benefits.

Importantly, the authors are cautious: they do not claim that all people with bipolar disorder or schizophrenia have HCV. Rather, their study suggests a subset may be affected by viral infection in a way that contributes to neuropathology.

This discovery also aligns with growing evidence from other studies that HCV infection can affect the brain, even in patients without obvious liver damage. Chronic HCV has long been linked to neurocognitive impairments — such as difficulties with attention, memory, and executive function — likely mediated by inflammation or neurotoxic by‑products.

Furthermore, there is some clinical evidence that treating HCV may reduce psychiatric risk. For example, in a large, real-world Taiwanese cohort, patients who cleared HCV following antiviral therapy showed a markedly reduced risk of developing schizophrenia.

Taken together, these findings lend strong support to what some have called the “viral hypothesis” of psychiatric illness — the idea that viral or microbial infections might contribute to the onset or progression of conditions like schizophrenia and bipolar disorder.

Of course, more research is necessary. We must learn how frequently HCV reaches the choroid plexus, what mechanisms allow it to persist there, and whether treating it can meaningfully improve brain function and psychiatric symptoms. Nevertheless, this discovery marks a significant shift: mental illness may not only be a disease of the mind or genes — in some cases, it may also be a disease of infection.

References (selected):

-

Johns Hopkins Medicine study: detection of HCV in choroid plexus in schizophrenia and bipolar disorder.

-

Original research in Translational Psychiatry.

-

Commentary in Psychiatric Times.

-

Review of HCV-associated neuropsychiatric disorders.

-

Cohort study showing reduced schizophrenia risk after HCV treatment.

News in the same category

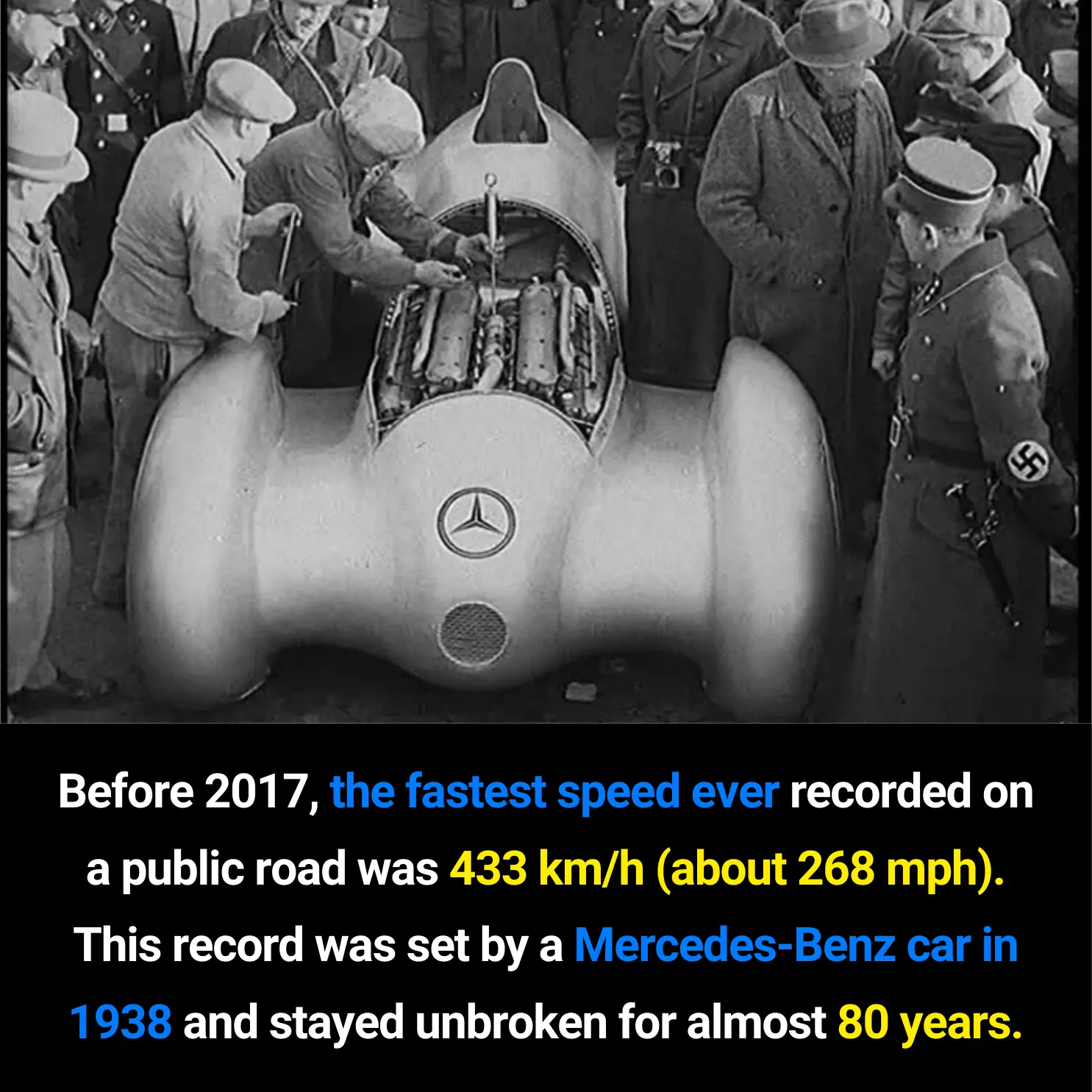

The Evolution of Public Road Speed Records: From the Mercedes-Benz W125 to the Koenigsegg Agera RS

New Antiviral Chewing Gum Made From Lablab Beans Shows Strong Virus-Neutralizing Potential in Lab Tests

Misconceptions That Turn Water Purifiers Into a Source of Illness — Stop Them Before They Harm Your Family

A New Breakthrough: Magnetic Microrobots Designed to Navigate Blood Vessels and Stop Strokes

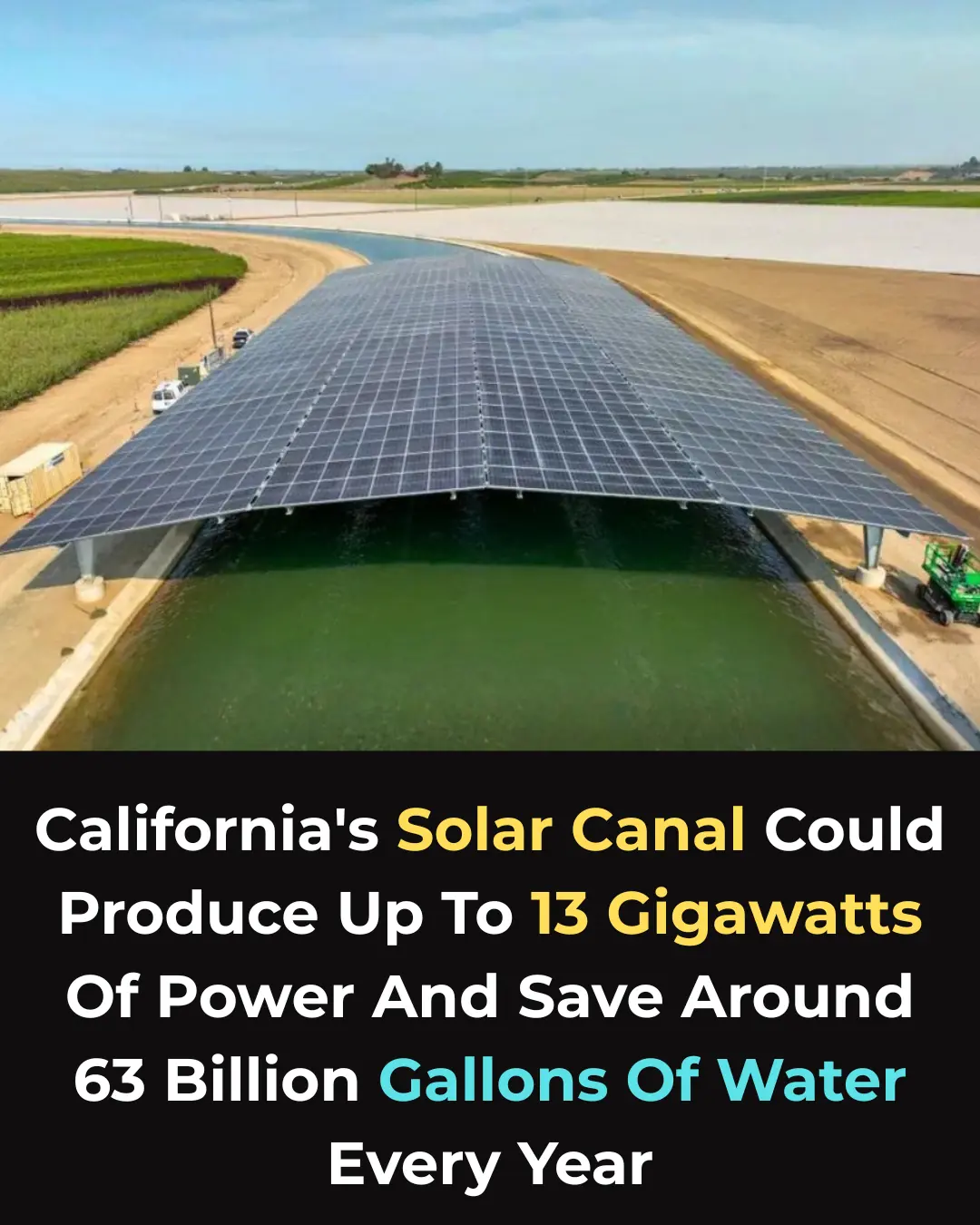

A Dual Climate Solution: Solar Panels Over Canals Could Save Billions of Gallons of Water

Regenerative Medicine Milestone: Stem-Cell Trial Restores Motor Function in Paralyzed Patients

From Crow to Cleaner: How Feathered Geniuses Are Fighting Litter in Spain

Using Crow Intelligence to Fight Pollution: Inside Sweden’s Corvid Cleaning Project

From Stone to Shelter: Innovative Housing Beneath France’s Historic Bridges

Redefining Public Restrooms in South Korea: Hygiene, Dignity, and Accessibility for All

How Cyclic Sighing Became One of the Most Effective Breathing Techniques for Reducing Anxiety

Top 10 Safest Places if World War 3 Broke Out

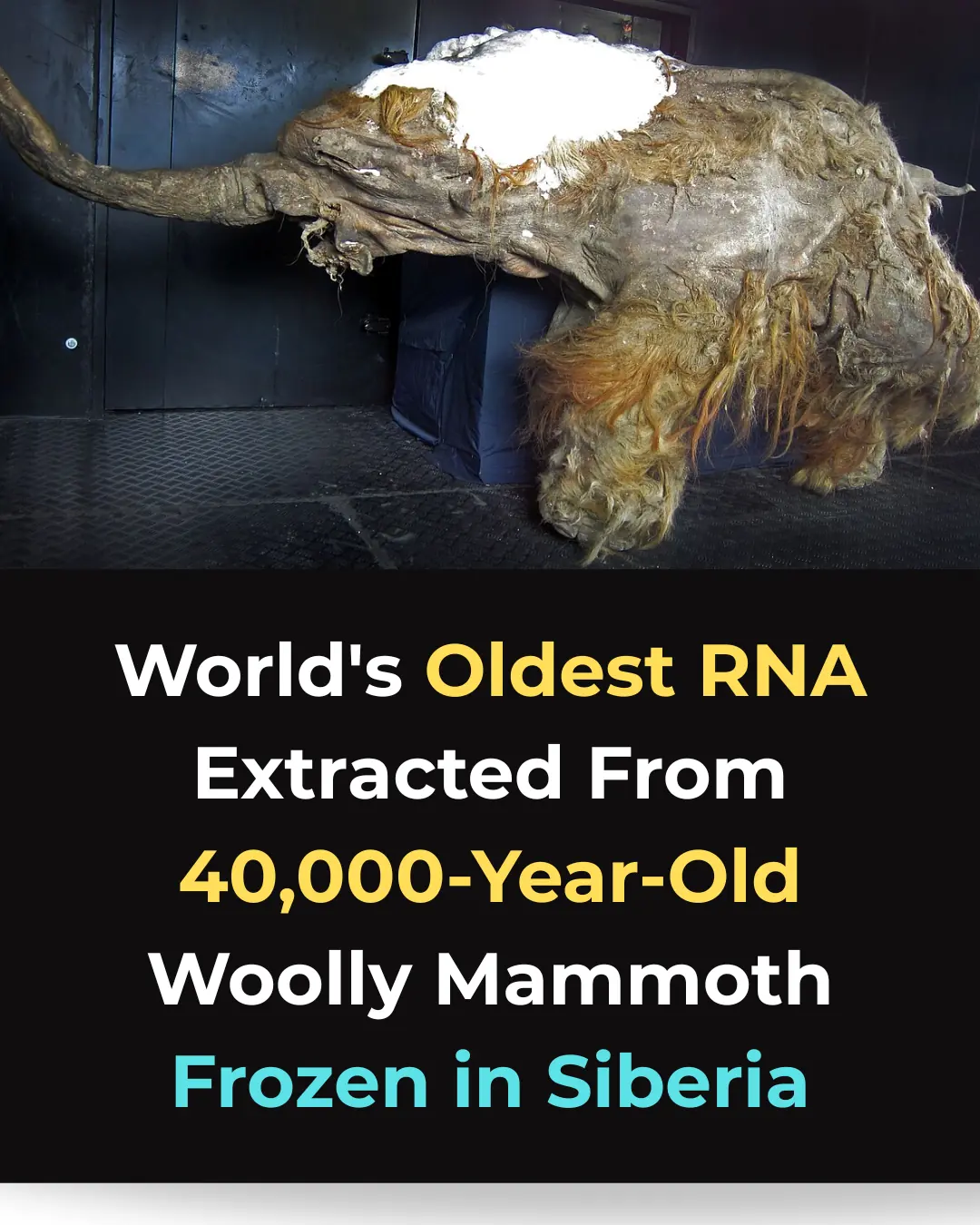

Scientists Sequence the World’s Oldest RNA from a 40,000-Year-Old Woolly Mammoth

Novel Neural Pathway Identified as Key to Reversing Autism-Related Behaviors

Why seniors should keep their socks on even at home

What Once Seemed Impossible: Lab-Grown Spinal Cord Sparks Hope for Millions

Lab-Grown Spinal Cord Tissue Marks a New Era in Paralysis Treatment

How Hormonal Birth Control May Reshape the Brain: New Neuroscience Insights

News Post

The Day a Burned Little Boy Met His Hero in Blue.

The Princess Who Saved Her Father.

The Mailman Who Became Her Shelter.

Forty-Eight Hours of a Mother’s Love.

Jack Andraka: The 15-Year-Old Innovator Who Sparked a New Wave of Early Cancer Detection Research

The Evolution of Public Road Speed Records: From the Mercedes-Benz W125 to the Koenigsegg Agera RS

New Antiviral Chewing Gum Made From Lablab Beans Shows Strong Virus-Neutralizing Potential in Lab Tests

10 Effective Ways to Reduce Dust in Your Home – Keep Your Living Space Clean and Healthy

Misconceptions That Turn Water Purifiers Into a Source of Illness — Stop Them Before They Harm Your Family

The Best Natural Remedies to Treat and Prevent Varicose Veins Effectively

People Who Do This Every Morning Have Better Circulation and More Energy

The hidden signs your body sends before diabetes strikes

Vaseline Uses and Benefits for Skin, Lips, and Hair

10 simple ways to reduce dust at home that most people overlook

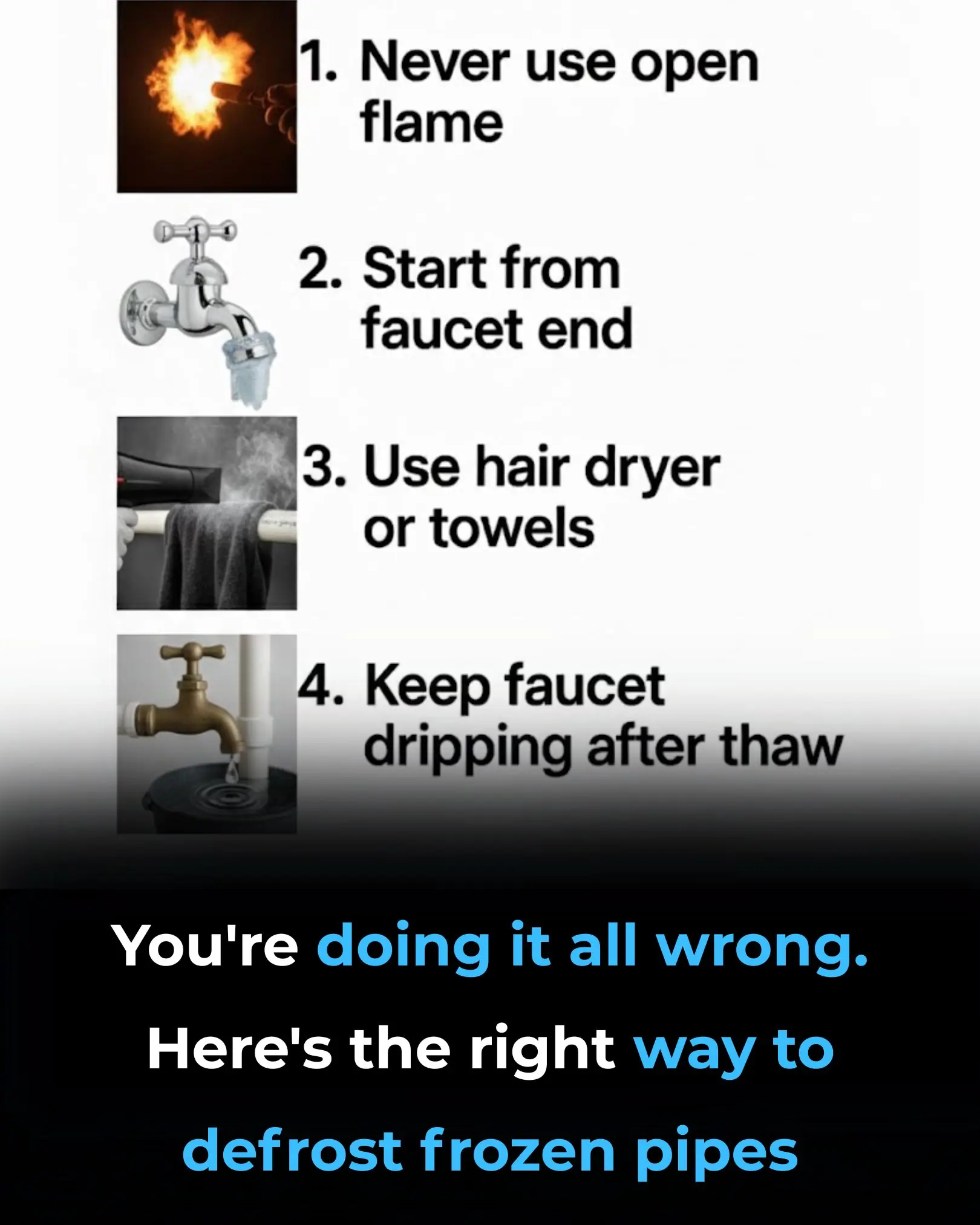

You’re Doing It All Wrong: Here’s the Right Way to Defrost Frozen Pipes

7 Powerful Fruits to Preserve Muscle Strength and Energy After 50

I Didn’t Know!

The #1 FASTEST way to reverse fatty liver naturally

Could the bacteria in your nose be causing Alzheimer’s?