In Sweden, You’re Not Allowed to Leave Your Dog Alone for More Than Six Hours, Here’s the Reason

The Six-Hour Rule: What Sweden Can Teach the World About Caring for Dogs

Imagine leaving for work in the morning, locking the door behind you, and not returning until dinner. Now imagine that, during those long hours, someone waits for you—no phone, no books, no distractions—just silence, stillness, and the hope that you’ll come back soon. For millions of dogs, this isn’t a thought experiment. It’s reality.

In Sweden, that quiet, lonely wait isn’t simply noticed—it’s recognized in law. By regulation, you cannot leave your dog alone for more than six hours without human contact or a walk. This isn’t about coddling pets or indulging in sentimental thinking. It’s about acknowledging dogs for what they truly are: emotionally intelligent, socially wired beings who perceive time, form deep attachments, and feel loneliness in very real ways.

While many countries still treat long hours of isolation as a normal part of a dog’s life, Sweden treats it as a welfare concern. This distinction isn’t just a legal curiosity—it’s a cultural statement about empathy, responsibility, and the mutual presence that animals and humans depend on.

A Science-Based Law, Not Just Sentiment

At first glance, Sweden’s six-hour rule might seem like a cultural nicety—a sweet, progressive touch from a country already known for its social welfare policies. But the foundation is solid science, not sentimentality.

Contrary to the long-held belief that dogs “just sleep the day away,” studies have shown they are acutely aware of how long they’ve been alone. Their circadian rhythms—the internal clocks regulating sleep, activity, and mood—are finely tuned. Research in Applied Animal Behaviour Science reveals a clear pattern: after short absences, dogs remain relatively calm, but once alone for four to six hours, their stress responses increase noticeably. They may pace, whine, bark, become hyperactive, or withdraw entirely. These changes aren’t random—they’re biological signals of emotional strain.

This is rooted in their evolutionary history. Dogs descended from wolves—pack animals whose survival depended on constant social connection. Thousands of years of domestication have only deepened their reliance on companionship, especially with humans. “Being alone is not natural for a dog,” says animal welfare expert Jens Jokumsen. Even if a dog sits quietly while you’re gone, it doesn’t mean they’re content; some simply shut down, conserving emotional energy while waiting for your return.

The six-hour limit wasn’t chosen arbitrarily—it reflects the point at which solitude becomes harmful for most dogs. In Sweden, that knowledge isn’t just academic; it’s embedded in law and enforced with real consequences. The goal isn’t to punish owners but to redefine good care: not merely food and shelter, but consistent, meaningful connection as a biological need—not a luxury.

The Emotional Cost of Canine Isolation

We often say dogs are “part of the family,” but if we believed that fully, would we routinely leave them alone for eight, ten, or even twelve hours a day?

Dogs don’t understand the concept of workdays or commuting. They only know that the person they depend on has vanished, and they don’t know when—or if—you’ll return. That uncertainty can be deeply distressing.

Some dogs express this anxiety loudly, through howling, barking, or destruction. Others suffer silently. Pet cameras often reveal hours of pacing, trembling, or lying motionless, eyes fixed on the door. Owners may take comfort in the idea that their dogs “just sleep,” but for many, those naps are fragmented and restless.

The pandemic amplified this problem. During lockdowns, dogs enjoyed unprecedented companionship. But as life returned to normal, many pets—especially those who had never been left alone—developed separation anxiety. Shelters across Europe and North America saw increases in surrenders, not because dogs misbehaved, but because their needs were underestimated.

Veterinary behavioral research confirms that chronic loneliness can cause symptoms similar to human depression: reduced appetite, withdrawal from play, restless pacing, and excessive clinginess. Over time, this emotional strain can affect physical health, just as it does in people. As Jokumsen bluntly warns, “If you don’t have time for the dog, don’t get one.”

What Sweden Gets Right About Animal Welfare

In Sweden, dogs are seen not as accessories, but as sentient beings with legal rights. The six-hour rule is just one part of a larger framework that protects animal well-being.

By law, Swedish dogs must be walked several times daily, have access to daylight, and receive mental stimulation. Long-term crating is prohibited, tethering is limited to one hour, and even indoor-kept dogs must be able to look out of a sunlit window.

Other animals benefit from similar principles: cows must graze outdoors for part of the summer, guinea pigs must be kept in pairs to prevent loneliness, and all animals must have environments suited to their behavioral needs. Violations can result in fines, bans on ownership, and even prison time.

This might seem extreme compared to countries where dogs are routinely confined for entire workdays without legal consequence. But Sweden’s approach sends a clear message: animal welfare is not optional or secondary—it is a societal priority backed by law.

Redefining Responsible Dog Ownership

Sweden’s model challenges owners everywhere to think differently about responsibility. It’s not enough to provide food, shelter, and occasional affection. True care means integrating a dog’s needs into daily life, even when inconvenient.

That begins with time—intentional, structured time. Owners may need to coordinate schedules, hire walkers, use doggy daycare, or negotiate flexible work arrangements. These aren’t luxuries; they’re tools for meeting a dog’s minimum welfare needs.

Mental stimulation is equally important. Dogs are natural explorers, problem-solvers, and scent-seekers. Quick bathroom walks don’t satisfy these instincts. Varying routes, offering puzzle toys, and playing scent games can prevent boredom and anxiety.

The key question for any potential owner is simple: Can I meet this animal’s needs every day, for its entire life? As Jokumsen reminds us, “It’s not a human right to have a dog.”

What Our Treatment of Animals Says About Us

Sweden’s law is more than a policy—it’s a reflection of cultural values. It recognizes that boredom, anxiety, and loneliness are real forms of suffering. It forces us to listen not just to the loud cries of distress, but also to the quiet, patient suffering that can be easy to overlook.

Empathy, here, is not sentimental—it’s practical, enforceable, and grounded in science. Laws like this expand the moral circle to include beings who cannot advocate for themselves. They remind us that care is not just about preventing harm, but about providing presence, comfort, and security.

Whether or not we live in Sweden, we can choose to adopt its ethos: showing up for our dogs not just when it’s convenient, but consistently—every single day. Because owning a dog isn’t about possession. It’s about partnership, loyalty, and meeting a living being’s needs in return for the trust they give us without question.

News in the same category

The Truth About Eating the Black Vein in Shrimp Tails

This is why you should keep the bathroom light on when sleeping in a hotel

Leaving your hotel bathroom light on at night might seem unnecessary, but it could be a small habit that makes a big difference for your comfort and safety. From preventing nighttime accidents to deterring intruders, experts say this simple tip can protec

The Mystical Gaboon Viper, Master Of Disguise And Deadly Accuracy

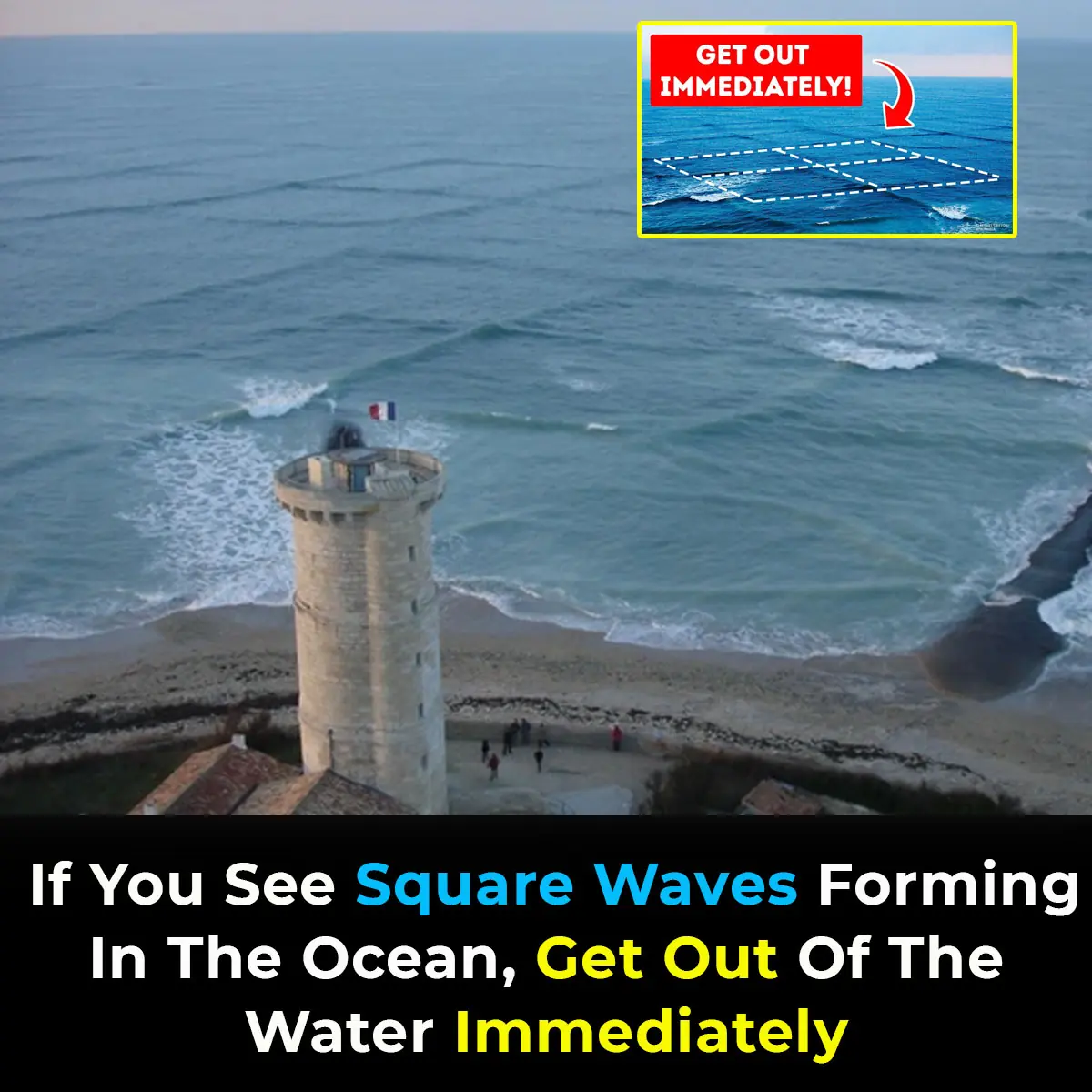

If You See Square Waves Forming In The Ocean, Get Out Of The Water Immediately

A Greenland Shark Born in 1620 is Still Alive Four Centuries Later

15 Things You Should Never Plug Into A Power Strip

China is Developing a Levitating Train That Could Travel From New York to Chicago in Just Two Hours

The world’s oldest woman, who lived to 117, ate the same meal every day throughout her life

Emma Martina Luigia Morano, the world’s oldest woman at the time of her passing, credited her extraordinary 117 years of life to a mix of genetics, resilience, and one very peculiar daily diet. Her remarkable story spans two World Wars, personal tragedy

TikTok’s ‘Vabbing’ Trend Sparks Debate: Does It Attract Partners?

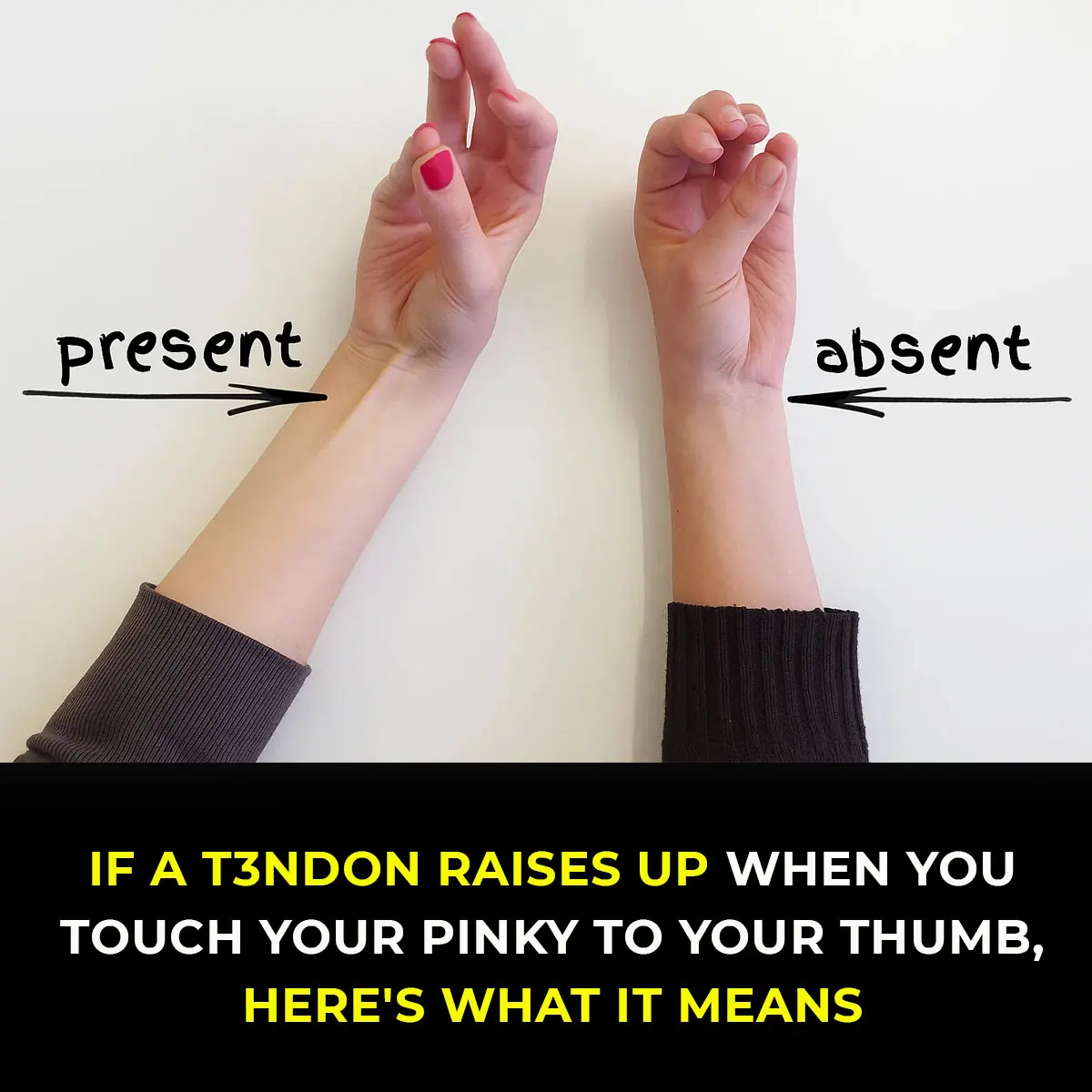

A A tendon raises up when you touch your pinky to your thumbraises up when you touch your pinky to your thumb

The Hidden Meaning Behind Leg-crossing — It’s More Than Just Comfort

The Sh0cking Truth Behind Your Ankle Bracelet And What It Reveals About You — It’s More Than Just Jewelry

For many, an ankle bracelet is just a delicate, eye-catching piece of jewelry. But behind its shimmer lies a rich tapestry of history, tradition, and hidden symbolism that stretches across cultures and centuries.

Lost Underwater City Near Noah’s Ark Site Could Rewrite Biblical History Forever

The discovery of an underwater city found by the 'resting place of Noah's Ark' is a revelation that may lead to the Bible story being re-written.

11 Heartbreaking Yet Essential Signs Your Dog May Be Nearing the End — And How to Give Them Comfort Until the Last Moment

When you notice these signs, your role transforms from caregiver to emotional anchor. This is the time to be fully present — offering touch, reassurance, and unconditional love.

Harvard Professor Warns: Object Heading Toward Earth Could Be Something Beyond Nature

A massive interstellar object, 3I/ATLAS, is racing toward Earth, and one Harvard astrophysicist believes it may not be natural. With missing comet features and a suspicious trajectory, experts are now debating whether it could be an engineered spacecraft.

Mass Panic as ‘New Baba Vanga’ Predicts Majo Disasters Striking in Just One Month

A chilling prophecy from Japan’s so-called “New Baba Vanga” has triggered widespread fear and mass trip cancellations. Tourists are now abandoning travel plans as the forecast warns of a catastrophic natural disaster hitting in early July 2025.

What Is SPAM Meat? History, Origin, Ingredients, and How It Became a Global Food Icon

SPAM — the world-famous canned meat — has been sold over 8 billion times and is loved in more than 40 countries. From its humble beginnings during the Great Depression to its role in World War II, here’s the complete story of SPAM’s origin, ingred

Scientists Reverse Aging of a 53-Year-Old’s Skin Cells to That of a 23

News Post

10 Symptoms That May Reveal Health Problems

Experts warn: Don’t swap your oven for an air fryer

Get Rid of Throat Mucus Faster With These Home Treatments (Evidence Based)

Clear Throat Mucus Fast With These Tried-and-Tested Remedies They Don’t Want You to Know

9 Warning Signs of Magnesium Deficiency You Shouldn't Ignore

Poor Postcancer Surgery Outcomes Tied to 3 Factors

Teamwork Boosts Primary Care Doc Job Satisfaction, Cuts Stress

HIV Was Successfully Eliminated from Human Immune Cells Using CRISPR Gene Editing in Landmark Study

Scientists Discover An “Off Switch” For Cholesterol—And It Could Save Millions Of Lives

How to Treat Urinary Tract Infection (UTI) Naturally According to Science

4 Common Causes of Body Pain on the Right Side

The Truth About Eating the Black Vein in Shrimp Tails

12 Subtle Vitamin D Deficiency Symptoms That Most People Ignore

What Your Heart Experiences When You Drink Energy Drinks

How to Eat Right for Your Blood Type

Eyes Full of Hope, Heart Full of Trust.

When to Worry About Veins That Appear Out of Nowhere

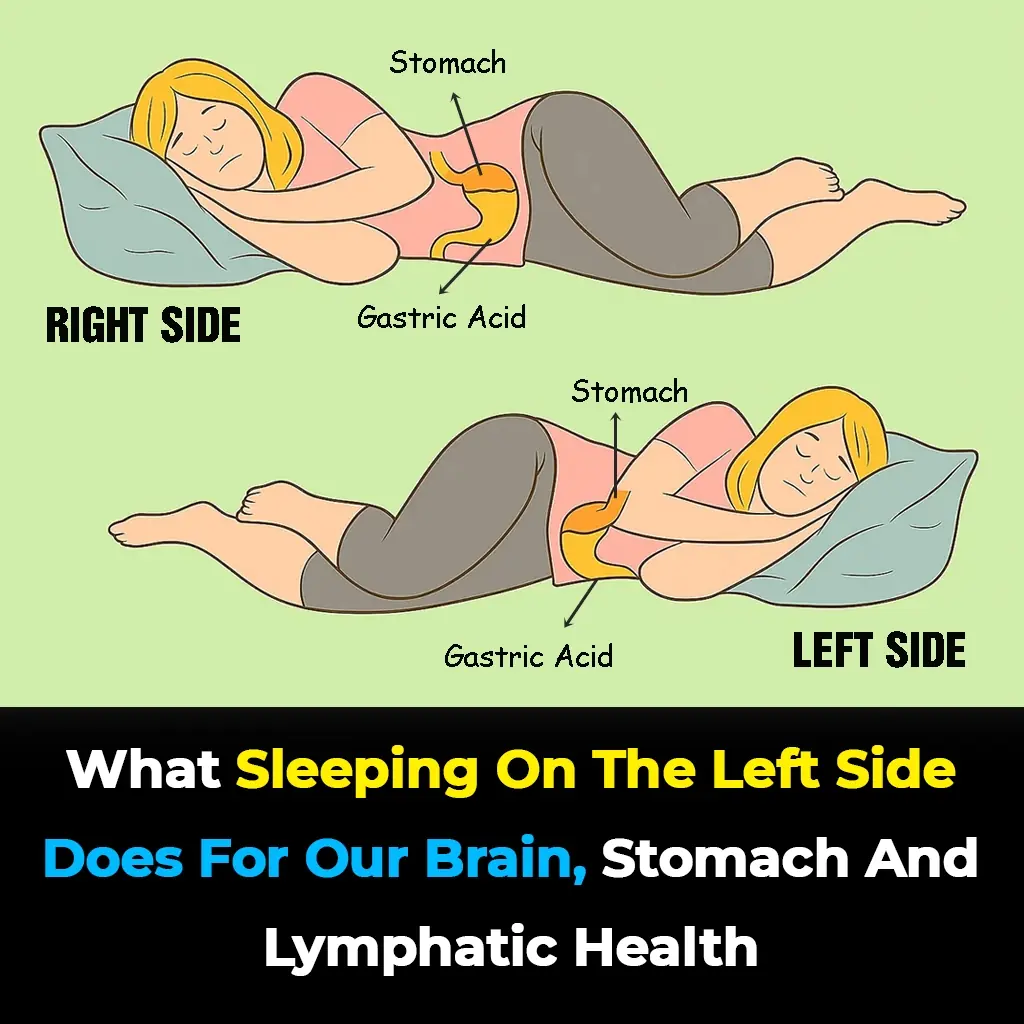

This is what sleeping on the left side does for our brain, stomach & glymphatic health

Sleeping position might be the last thing you think about before bed, but it can have a powerful impact on your health. Experts say that lying on your left side could improve digestion, support brain detox, ease back pain, and even enhance circulation.

I Haven’t Seen My Daughter in 13 Years — Then a Letter Arrived from a Grandson I Never Knew

This is why you should keep the bathroom light on when sleeping in a hotel

Leaving your hotel bathroom light on at night might seem unnecessary, but it could be a small habit that makes a big difference for your comfort and safety. From preventing nighttime accidents to deterring intruders, experts say this simple tip can protec