Loss of Smell May Be One of the Earliest Warning Signs of Alzheimer’s Disease

Loss of Smell May Signal Alzheimer’s Years Before Memory Declines

Imagine being able to detect Alzheimer’s disease long before memory problems or confusion begin—simply by paying attention to changes in your sense of smell. New research from the German Center for Neurodegenerative Diseases (DZNE) in collaboration with Ludwig-Maximilians-Universität München (LMU) suggests that a declining ability to perceive odors could be one of the earliest warning signs of Alzheimer’s disease. This discovery opens the door to earlier diagnosis and, potentially, more effective interventions at a stage when the disease may still be slowed.

Alzheimer’s disease is traditionally diagnosed only after noticeable cognitive symptoms appear, by which time significant and often irreversible brain damage has already occurred. However, scientists have long suspected that subtle sensory changes may emerge years earlier. The new study provides strong biological evidence supporting this idea, linking early olfactory dysfunction directly to disease-related changes in the brain.

At the center of this process are microglia, the brain’s resident immune cells. Microglia normally protect the nervous system by removing damaged cells and maintaining healthy neural connections. According to the researchers, in the early stages of Alzheimer’s disease these cells begin to behave differently. They selectively dismantle important nerve connections between the olfactory bulb—responsible for detecting and processing smells—and the locus coeruleus, a small but vital brainstem region involved in attention, sensory integration, and cognitive alertness.

This destructive process is triggered by subtle alterations in the membranes of nerve fibers. These changes act as a biochemical “eat-me” signal that attracts microglia, prompting them to eliminate the affected connections. As these links break down, the brain’s ability to process smells gradually deteriorates, often without the person noticing any other symptoms.

The researchers observed this mechanism in both animal models and human brain tissue. In mice genetically engineered to develop Alzheimer’s-like pathology, early loss of olfactory connections closely matched increased microglial activity. Importantly, similar patterns were found in post-mortem human brain samples. The team further confirmed their findings using positron emission tomography (PET) scans, which revealed immune-related brain changes associated with smell processing in living subjects.

These results suggest that olfactory impairment in Alzheimer’s disease is not merely a side effect of general brain degeneration, but rather the consequence of a specific immunological mechanism that begins very early in the disease’s progression. This aligns with growing evidence that neuroinflammation plays a central role in Alzheimer’s development, as highlighted by studies published in journals such as Nature Neuroscience and The Lancet Neurology.

The implications of this research are significant. If loss of smell can be reliably linked to early Alzheimer’s-related brain changes, simple and non-invasive smell tests could become valuable screening tools. Organizations such as the Alzheimer’s Association and the U.S. National Institutes of Health (NIH) have emphasized the urgent need for early biomarkers that can identify at-risk individuals before cognitive decline becomes apparent.

Ultimately, this discovery reinforces a broader shift in Alzheimer’s research: moving from late-stage treatment to early detection and prevention. While more studies are needed before smell testing becomes part of routine clinical practice, the findings suggest that something as subtle as a fading sense of smell could provide a crucial early window into one of the world’s most devastating neurodegenerative diseases.

News in the same category

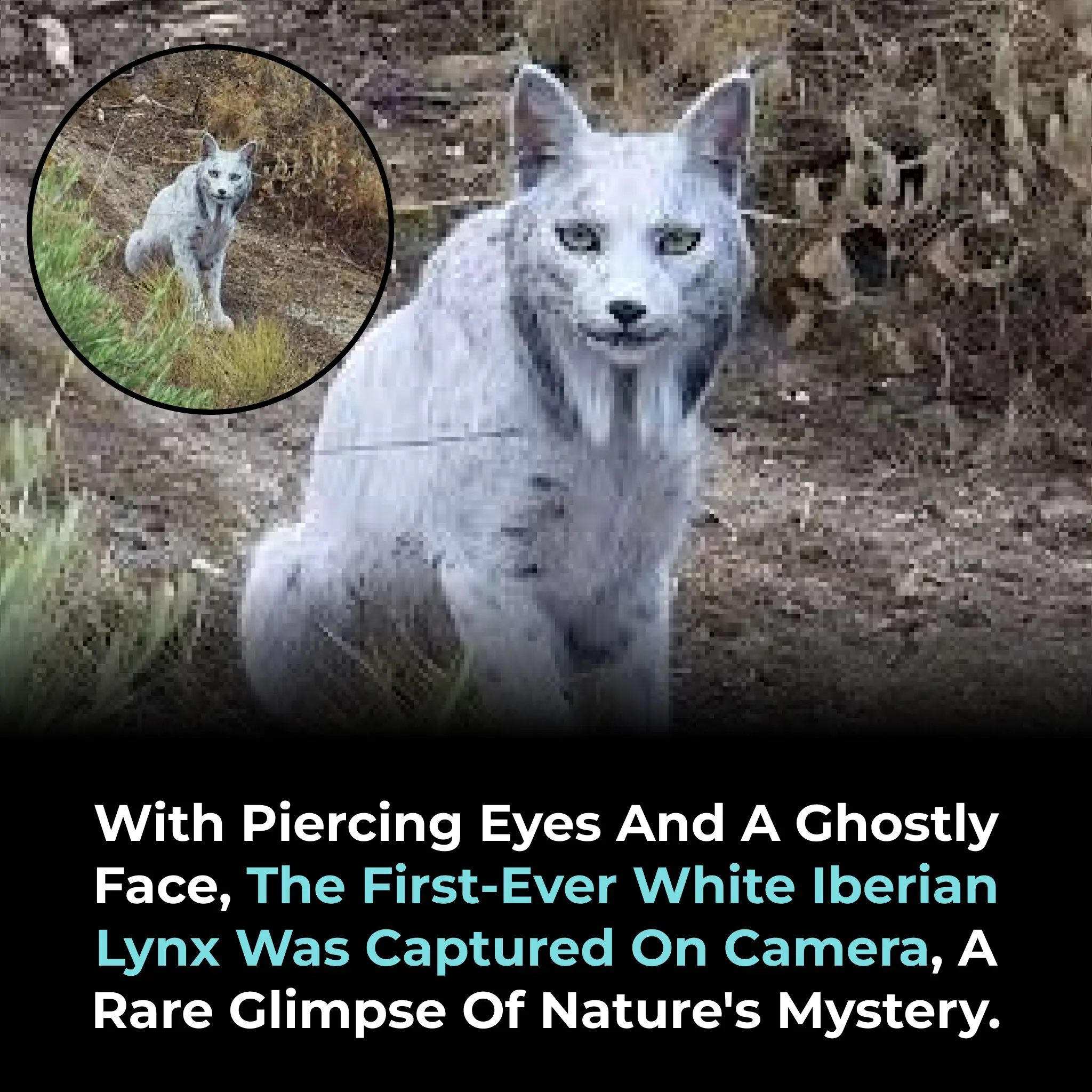

The First-Ever Leucistic Iberian Lynx Captured on Camera: A Rare and Powerful Symbol of Hope

Ultra-Processed Foods Linked to Increased Psoriasis Flare-Ups, Study Finds

Giant Pandas Officially Move Off the Endangered Species List: A Historic Conservation Triumph

Mexico City Passes Landmark Law Banning Violent Practices in Bullfighting: A Controversial Move Toward "Bullfighting Without Violence"

A Magical Bond: The Unlikely Friendship Between a Blind Dog and a Stray Cat in Wales

Chronic Gut and Metabolic Disorders May Signal Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s Years in Advance

Syros Cats: A Sanctuary for Feline Rescue and Compassion in Greece

The World Bids Farewell to Bobi, the World's Oldest Dog, at the Age of 31

The Cost of a Trip to Tokyo Disney is Now Cheaper Than Going to Disney in Florida

Groundbreaking Stem Cell Discovery Offers Hope for Rebuilding Myelin and Reversing Nerve Damage in Multiple Sclerosis

China Breaks Magnetic Field Record with Groundbreaking 351,000 Gauss Achievement

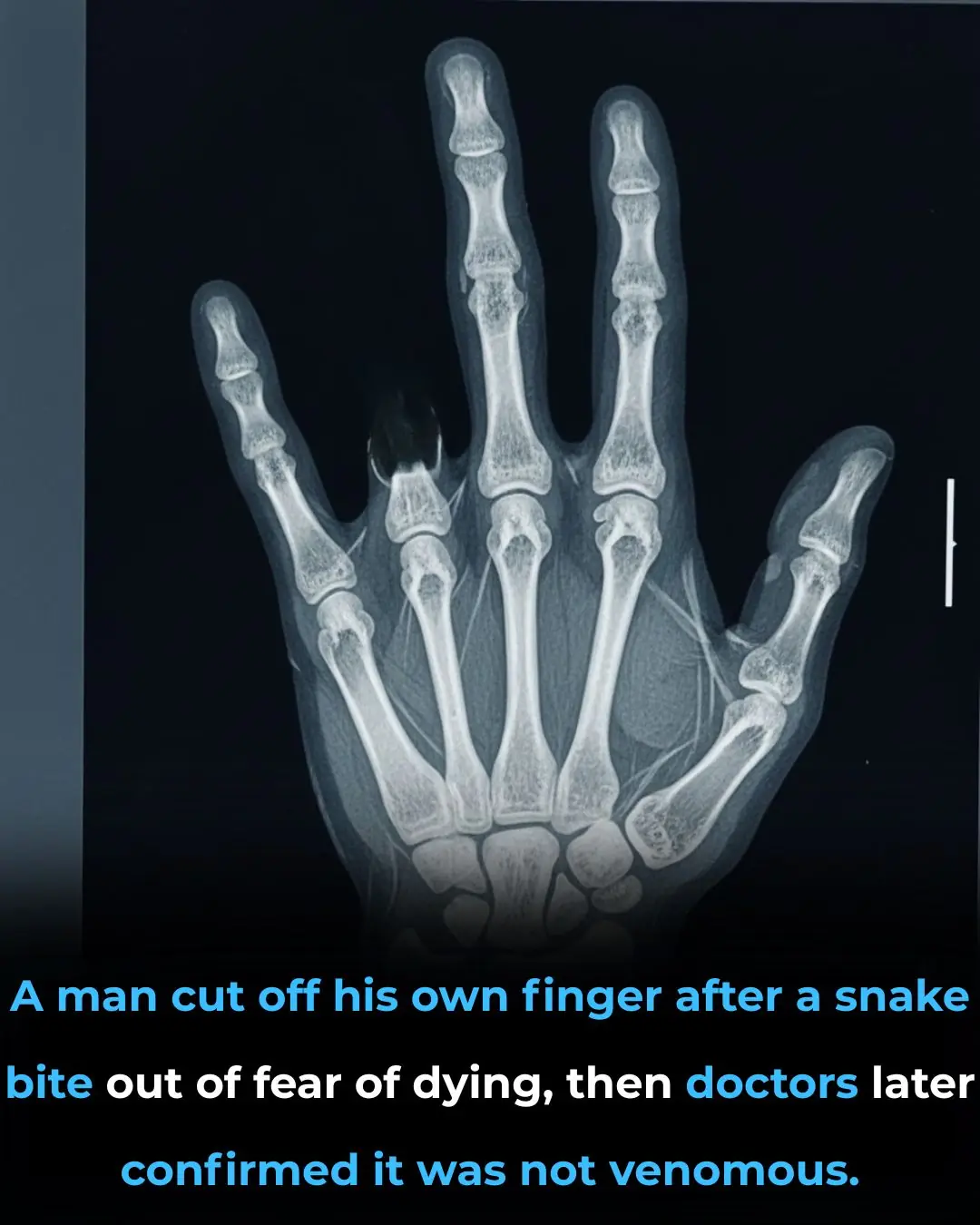

Man in China Cuts Off Finger After Snake Bite, Fearing Venomous Attack – Doctors Confirm It Was Harmless

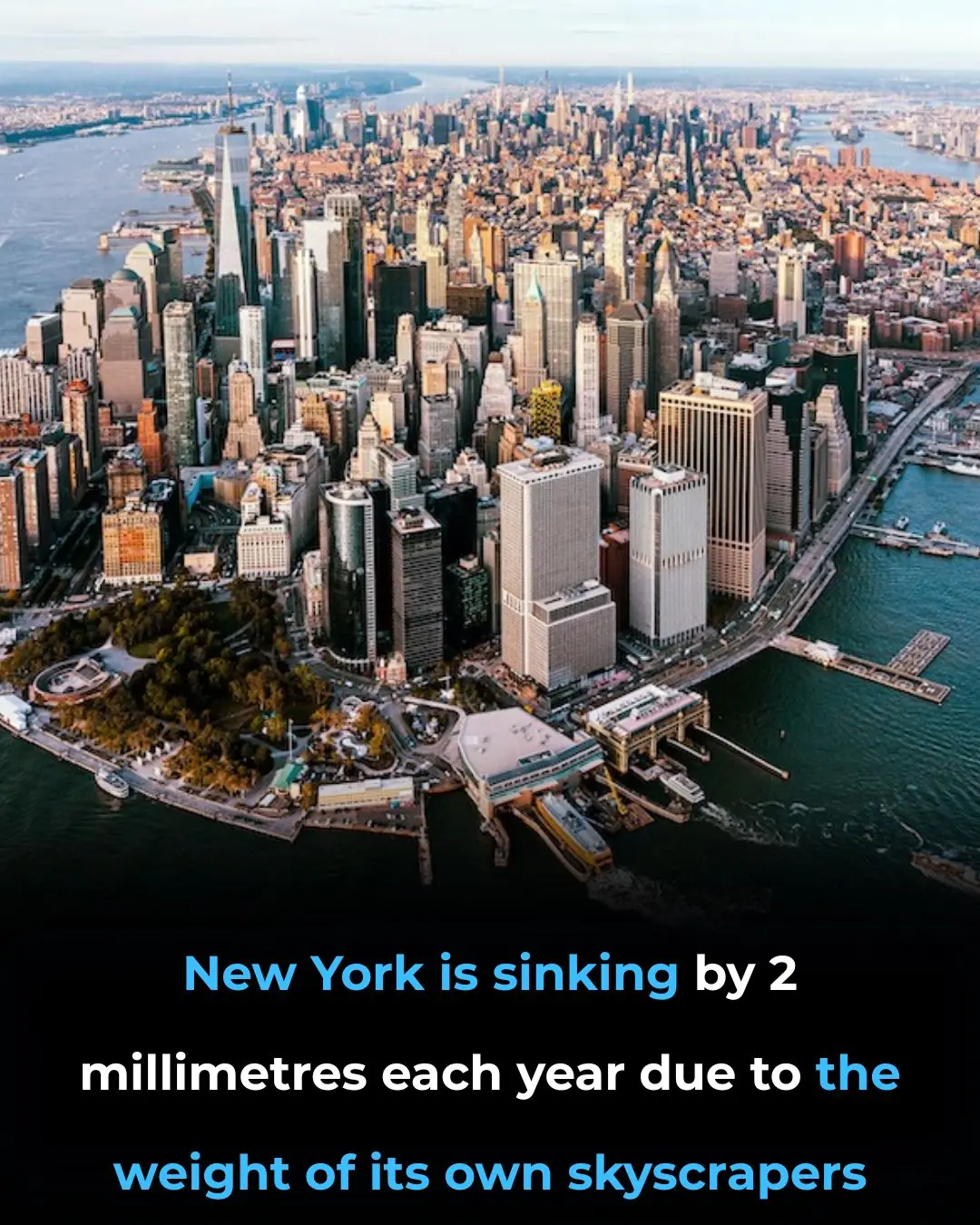

New Study Reveals New York City is Sinking: A Growing Threat from Subsidence and Rising Seas

Russia Blocks Access to Roblox Amid Growing Crackdown on Foreign Tech and LGBTQ+ Content

Mercedes Launches Premium Strollers in Collaboration with Hartan, Targeting the Luxury Baby Gear Market

Promising Signs of a Potential Long-Term HIV Cure: A Breakthrough Study from UCSF

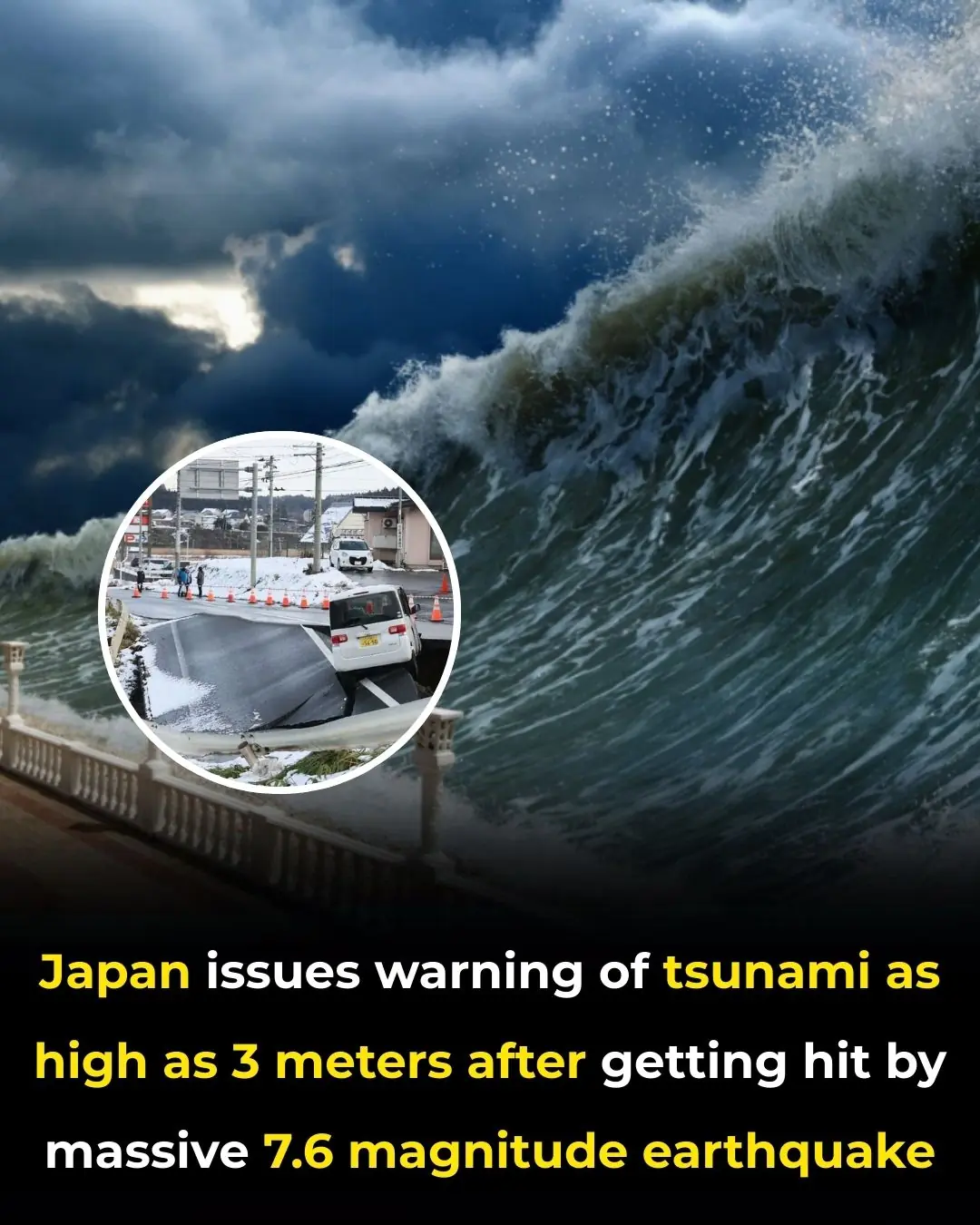

Japan Issues Tsunami Warning Following 7.6 Magnitude Offshore Earthquake

Elephant Burial Practices: A Deep and Emotional Connection to the Dead

News Post

Over 1,800 Lawsuits Filed Against Ozempic, Alleging Severe Side Effects and Misleading Marketing

The First-Ever Leucistic Iberian Lynx Captured on Camera: A Rare and Powerful Symbol of Hope

Ultra-Processed Foods Linked to Increased Psoriasis Flare-Ups, Study Finds

Giant Pandas Officially Move Off the Endangered Species List: A Historic Conservation Triumph

Twin Study Reveals Gut Microbiome's Role in Multiple Sclerosis Development

Mexico City Passes Landmark Law Banning Violent Practices in Bullfighting: A Controversial Move Toward "Bullfighting Without Violence"

World-First Breakthrough: Base-Edited Gene Therapy Reverses "Incurable" T-Cell Leukemia

Daily Tefillin Use Linked to Improved Blood Flow and Lower Inflammation

A Magical Bond: The Unlikely Friendship Between a Blind Dog and a Stray Cat in Wales

Daily Whole Orange Consumption Associated with 30% Reduction in Fatty Liver Prevalence

Phase I Trial: White Button Mushroom Powder Induces Long-Lasting PSA Responses in Prostate Cancer

Chronic Gut and Metabolic Disorders May Signal Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s Years in Advance

Tea Supports Bone Density While High Coffee Intake Linked to Bone Loss in Older Women

Syros Cats: A Sanctuary for Feline Rescue and Compassion in Greece

Rapamycin Reduces Lung Tumor Count by Up to 90% in Tobacco-Exposed Models

51-Year-Old Man Declared Cured of HIV Following Stem Cell Transplant for Leukaemia

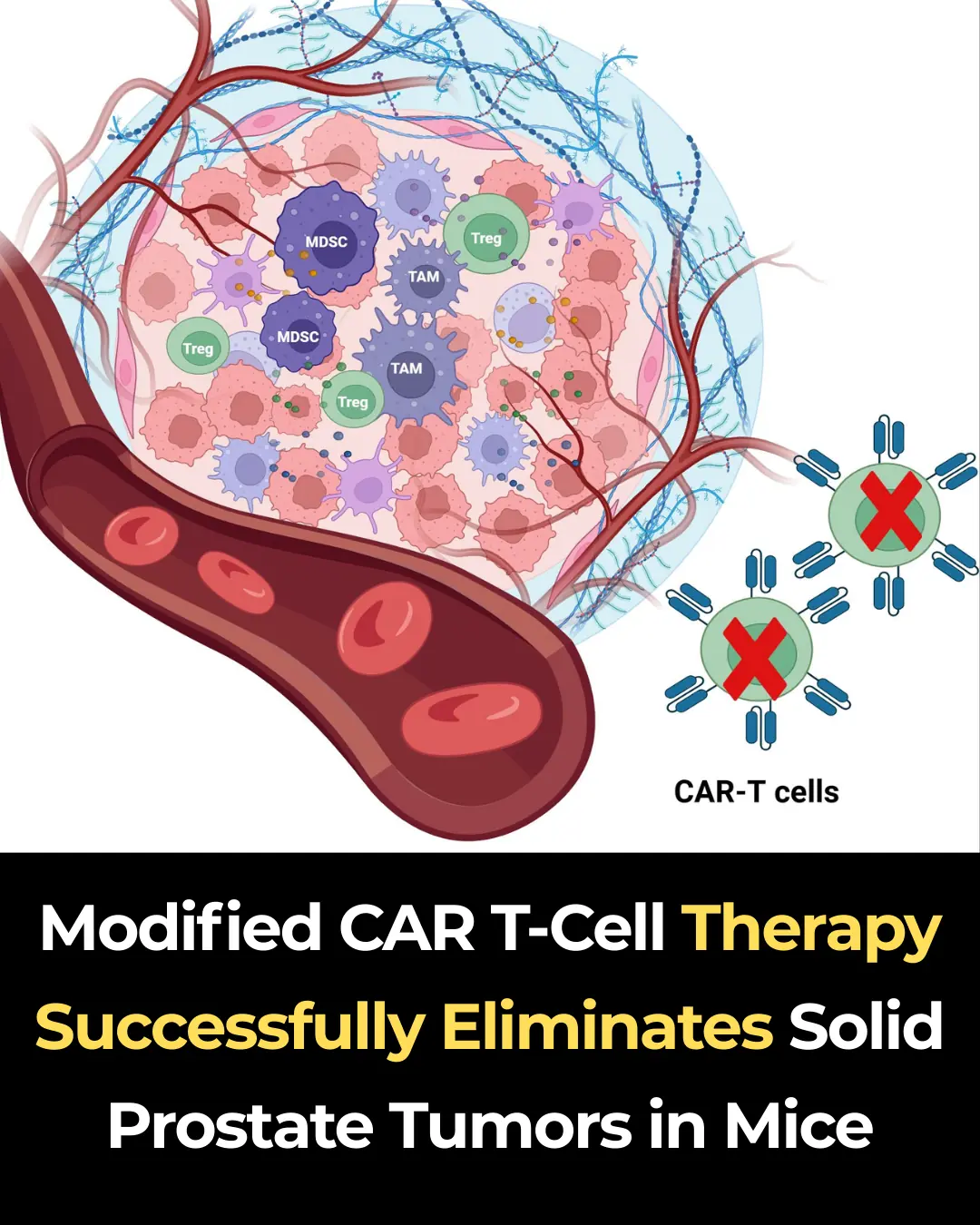

Modified CAR T-Cell Therapy Successfully Eliminates Solid Prostate Tumors in Mice

The World Bids Farewell to Bobi, the World's Oldest Dog, at the Age of 31

The Gut-First Approach: Berberine’s Impact on Microbiome Balance and Barrier Integrity