Tree-of-Heaven (Ailanthus altissima): Power, Potential, Uses, and Real-World Cautions

Tree-of-Heaven (Ailanthus altissima) is widely recognized as one of the toughest and most persistent urban trees on the planet. It breaks through pavement, survives in polluted or compacted soil, and rebounds even after severe cutting. Its remarkable endurance is the reason many cultures historically considered it a symbol of strength. In traditional Asian herbal practices, different parts of the plant—its bark, leaves, and roots—were used for issues such as digestive discomfort, parasitic infections, and various minor skin complaints. Modern laboratory research has begun examining its bitter chemical compounds, some of which demonstrate antimicrobial and anti-inflammatory activity under controlled conditions.

However, the same potent chemistry that gives this tree its reputation also introduces real risks. Misuse or careless handling can lead to irritation, allergic responses, or more serious effects. The following expanded guide explores its strengths, traditional and potential health-related benefits, external household applications, and the significant dangers associated with it. A strict safety disclaimer is included at the end.

Why Tree-of-Heaven Is Considered “Powerful”

Tree-of-Heaven exhibits an unusual combination of traits that make it exceptionally competitive:

Extreme hardiness: It grows in heavily contaminated zones, abandoned lots, construction debris, and soils where most plants cannot survive. It also tolerates drought and recovers quickly from physical damage.

Rapid regrowth: Its ability to send up new shoots from the root system or stump allows it to spread aggressively and makes removal extremely difficult.

Potent chemistry: The tree produces strong bitter quassinoids, particularly ailanthone, which have been studied for their insecticidal and antimicrobial effects. These chemicals also suppress the growth of nearby plants, giving the tree an ecological advantage.

High biomass yield: Because the tree grows so quickly, there is never a shortage of material for those documenting traditional practices or preparing carefully controlled external herbal preparations.

The essential point is that the tree’s biological and chemical force is undeniable—but precisely because of this, responsible handling is necessary.

Potential Health-Adjacent Benefits (Based on Traditional Use & Early Research)

These points summarize historical usage and pre-clinical findings. They are not medical claims and should not be used as justification for ingesting the plant.

-

Antimicrobial effects (laboratory): Extracts from the bark and leaves show activity against certain bacteria and fungi in controlled experiments.

-

Traditional antiparasitic use: Historically used for intestinal parasites in some folk systems.

-

Antidiarrheal (traditional): Decoctions of the bark or root bark appeared in old remedies for dysentery-like symptoms.

-

Astringent properties: Its strong bitterness may provide a toning effect when used externally in diluted preparations.

-

Anti-inflammatory potential: Studies indicate possible modulation of inflammatory pathways; folk practitioners sometimes used diluted topical washes for this purpose.

-

Insect-repellent potential: The odor and chemical profile can help deter some household pests in non-ingested forms.

-

Skin support (traditional): Very weak diluted rinses have been used for non-open, superficial skin issues.

-

Scalp cleansing rinse (folk): Some traditions describe diluted bitter rinses for a clean and refreshing feeling on the scalp.

-

Historic oral rinse use: Recorded in old texts, but no longer recommended due to toxicity concerns.

-

Fever-related support (traditional): Bitter tonics were once used for “cooling,” though modern internal use is discouraged.

-

Digestive stimulation (bitter theory): Bitters may enhance digestive processes in theory, but Ailanthus is unsafe for self-dosing.

-

Historic wound-adjacent cleansing: Extremely diluted washes were occasionally used, but should not replace modern medical wound care.

-

Respiratory environment effect: As a robust urban tree, it improves greenery, though its pollen may worsen allergies.

-

Household cleaning applications: Infusions used in cleaning solutions may help reduce surface grime.

-

Mood/environmental ritual: Some users enjoy creating gentle external herbal rinses, although strong odors or dust should be avoided.

Safe Homemade Uses (External or Household Only)

Internal consumption is not recommended unless under the supervision of a trained clinical herbal professional.

1. Mild Diluted External Rinse

For: Occasional scalp or skin rinses on intact, non-irritated areas.

Method:

-

Collect a small amount of mature leaves while wearing gloves.

-

Wash and air-dry them.

-

Simmer 1 teaspoon dried leaf in 500 ml water for 5–8 minutes.

-

Cool completely and strain twice.

-

Perform a patch test for 24 hours.

Use only if no irritation occurs. Do not use around eyes, mouth, or broken skin. Apply at most 1–2 times weekly for short periods.

2. Ailanthus-Infused Cleaning Vinegar

For: Non-porous household surfaces only.

Method:

-

Fill a jar halfway with dried leaves or small pieces of bark.

-

Cover with white vinegar and infuse for 2–3 weeks.

-

Strain and label clearly: “Not for ingestion.”

Dilute 1:3 with water before spraying. Test on a small area first.

3. Dry Leaf Powder for Sachets

For: Drawer sachets to discourage insects (not for skin).

Method:

-

Fully dry the leaves in a ventilated area.

-

Grind while wearing gloves and a mask.

-

Store in breathable sachets and replace monthly.

4. Garden Use—With Serious Caution

Ailanthus extracts can inhibit surrounding plant life. Avoid applying leaf teas or compost material near gardens where food crops grow.

Safe Harvesting & Handling Practices

-

Correct ID is essential: large compound leaves, many leaflets, strong peanut-butter-like odor when crushed.

-

Wear protective gear: gloves, mask, long sleeves.

-

Avoid pollen season if you have allergies.

-

Dry in ventilated areas, away from sunlight.

-

Label clearly and keep away from children and pets.

Risks, Side Effects & When to Avoid Completely

-

Allergic skin reactions.

-

Respiratory irritation, especially for asthma sufferers.

-

Potential systemic toxicity if improperly ingested.

-

Eye and mucous membrane irritation.

-

Possible liver or cardiovascular stress in cases of heavy exposure.

-

Theoretical drug interactions.

-

Unsafe for pregnancy, children, pets, and individuals with chronic conditions.

-

It is also classified as an invasive species in many regions.

Safer Alternatives

-

For cleaning: classic vinegar, castile soap.

-

For rinses: chamomile, calendula.

-

For insect sachets: lavender, cedar chips.

Bottom Line

Tree-of-Heaven is a chemically powerful and ecologically dominant species. Its traditional uses and strong bioactive compounds make it interesting, but also potentially hazardous. For documentation, research, or limited external household applications, cautious handling is essential. Any therapeutic or internal use requires guidance from a trained professional.

Disclaimer

This expanded article is educational only. It does not diagnose, treat, cure, or prevent any disease. Do not ingest Ailanthus altissima without direct supervision from a qualified herbal practitioner. External and household uses require patch testing, labeling, and careful handling. Avoid use for children, pregnant individuals, people with chronic conditions, and anyone with allergies or asthma. Seek medical attention if any unusual symptoms occur after exposure.

News in the same category

The Hidden Power of Common Blue Violet (Viola sororia) and Its Homemade Uses

The Hidden Power of Banana Strings: Why You Should Never Remove Them Again

You Thought This Flower Was Just Decorative – Think Again…

Why You Should Embrace Purslane in Your Garden: 8 Compelling Reasons

Ginkgo Biloba: Ancient Leaf, Modern Power — Health, Medical & Homemade Benefits

Mullein: Exploring the Benefits of Leaves, Flowers, and Roots

The Versatility and Benefits of Orange Peel Powder

The Hidden Power of the Honey Locust Tree (Gleditsia triacanthos): Health, Healing, and Everyday Uses

Leaf of Life – The Healing Plant Growing in Your Backyard (And You Had No Idea!)

Benefits of this plant for the elderly: a natural ally for healthy aging

🌿 Natural Colon Cleanse: Myths, Facts, and Healthy Ways to Support Digestive Health

Weeds or Wonders? Discover the Hidden Treasures in These 4 Common Plants

The Hidden Power of Pine Nuts: Benefits, Nutritional Strength, and How to Use Them

10 Secrets You Need to Know Before Eating Okra

The Hidden Healing of Fig Leaves: Natural Support for Diabetes, Digestion, and More

With This Cream, My Grandmother Looked 35 at 65 – The Best Collagen Mask

Mimosa Pudica Tea: How to Prepare and Health Benefits

🌿 20 Gentle Benefits of Chewing Clove Daily — The Ancient Spice for Modern Wellness

News Post

Tips to deodorize the refrigerator

3 ways to make crispy roasted pork at home in a pan or fryer

5 Herbs Your Liver Wished You’d Start Eating More Often (Or At Least Try!)

Tips for hair treatment with okra, extremely effective against hair loss, baby hair grows bristling

This one vitamin could help stop you from waking up to pee every night

“How Indonesia’s Tarp Kiosks Are Redefining Public Drinking Water”

Just tried this and whoa

2 Simple and Effective Ways to Remove the Smell from Long-Frozen Meat

Lady had a bunch of empty old pill bottles

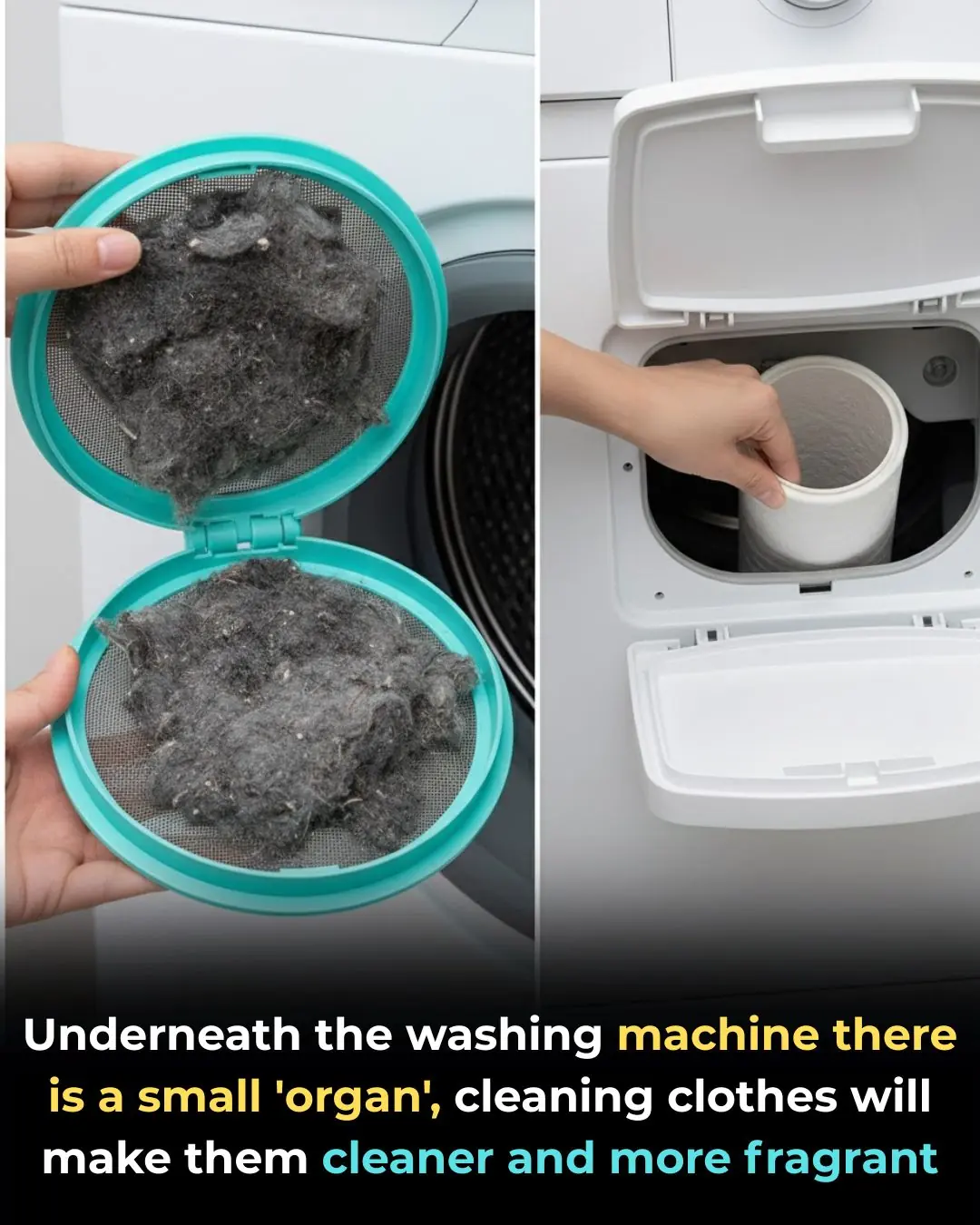

There’s a “Hidden Component” Under Your Washing Machine That Can Make Your Clothes Cleaner and Fresher

Wish I saw this sooner! Great tips!

Why Lung Cancer Targets Non-Smokers: The Hidden Kitchen Culprit You Might Not Know About

“Painting the Impossible: China’s Drone Experiments Turn Cliffs into Giant Artworks”

Dropping wind oil on garlic

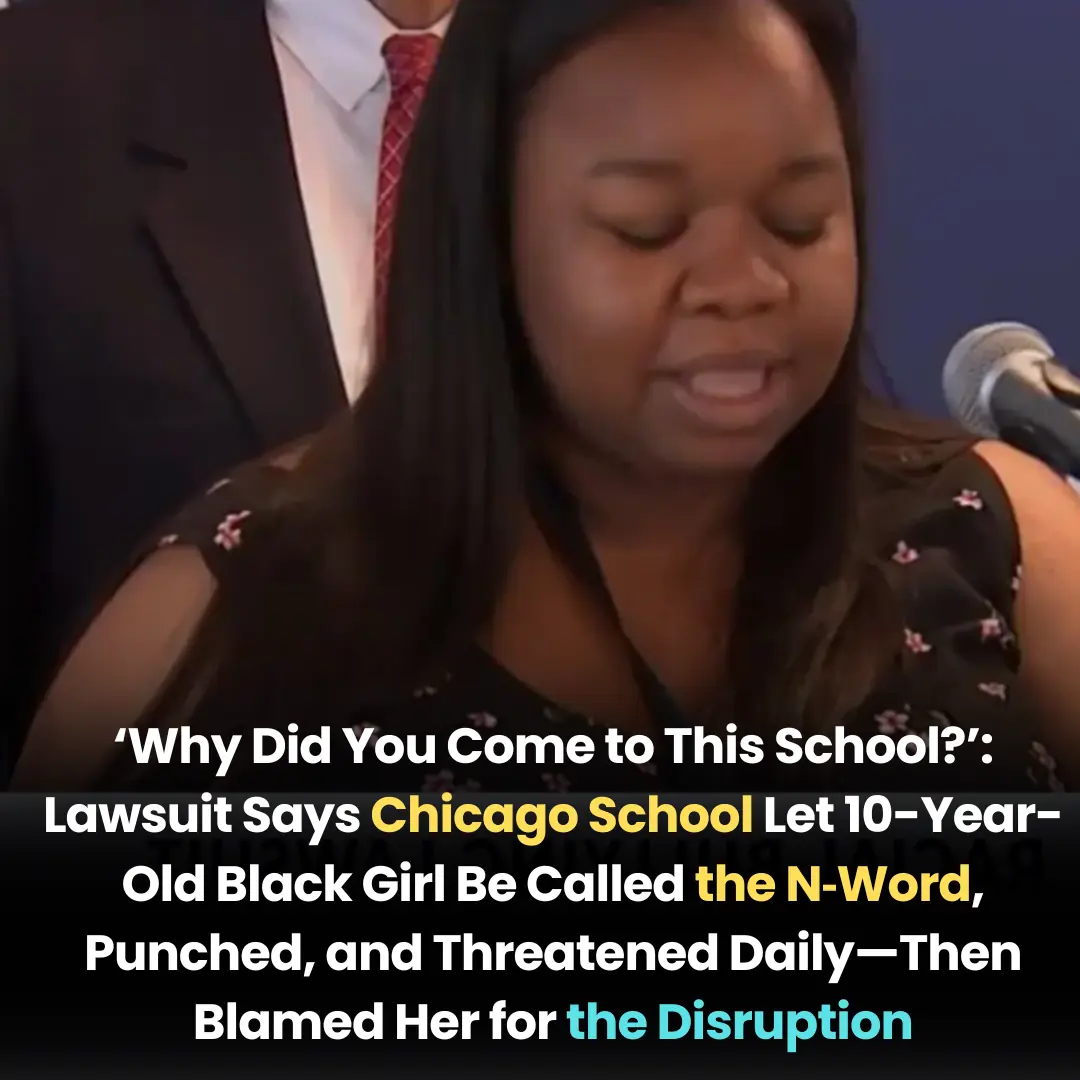

‘Why Did You Come to This School?’: Lawsuit Says Chicago School Let 10-Year-Old Black Girl Be Called the N‑Word, Punched, and Threatened Daily—Then Blamed Her for the Disruption

Don't boil chicken with salt and water, otherwise it will be fishy and turn red.

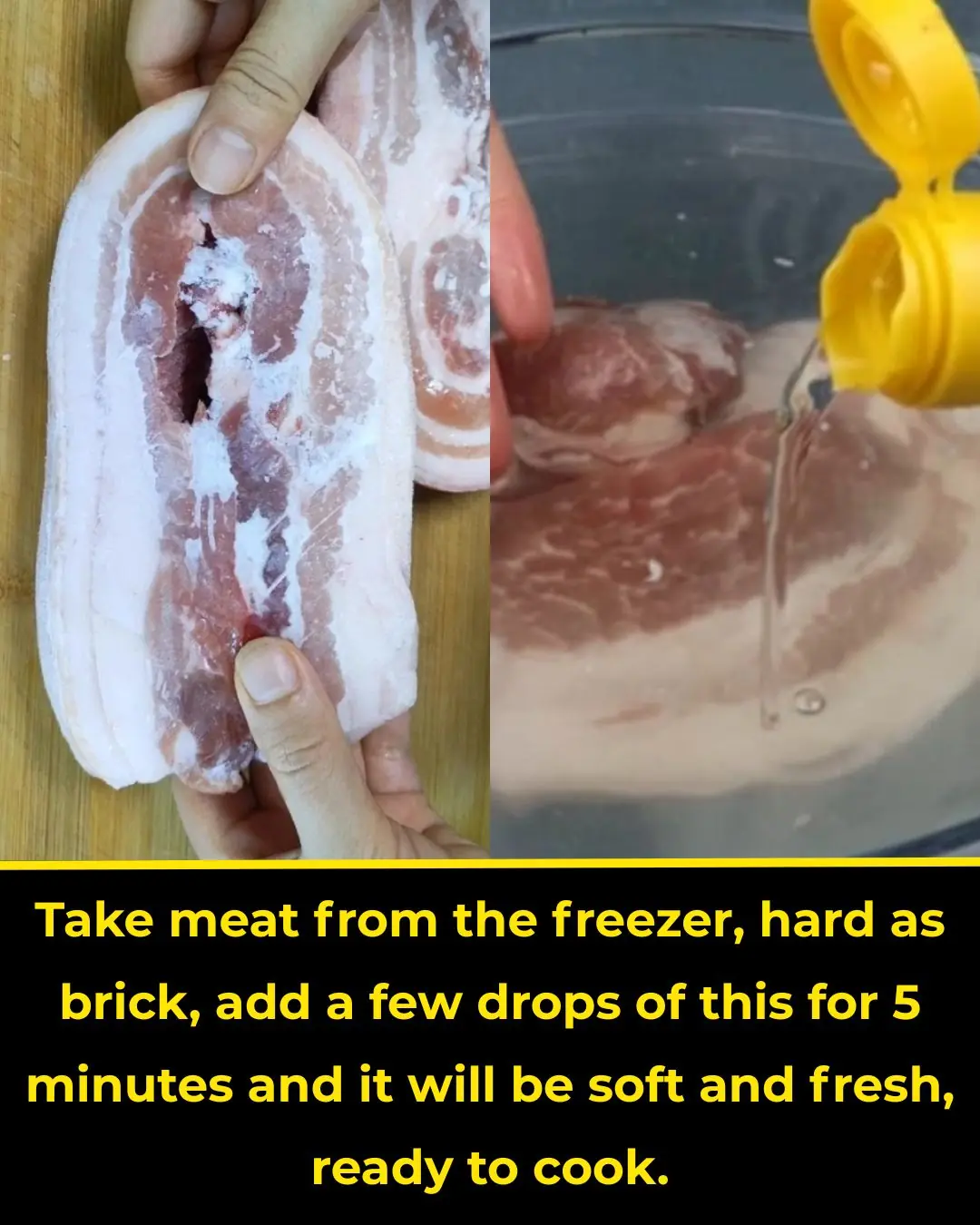

Take the meat from the freezer and it's hard as bricks

Your Mattress Getting Dirty and Smelly? Sprinkle This on the Surface — No Water Needed, and It’ll Look Fresh Again

Sink Trick You Should Always Do Before Vacation