Blue Blood in the Ocean: How Horseshoe Crabs Help Protect Human Health

The horseshoe crab, a living fossil that has existed for over 450 million years, is one of the most extraordinary creatures in the marine world, and it is particularly famous for its bright blue blood. Unlike humans and most animals, whose blood contains iron-based hemoglobin that turns red when it carries oxygen, horseshoe crabs rely on a copper-based protein called hemocyanin. This copper compound binds oxygen differently than hemoglobin does, producing a distinctive blue color in their circulatory fluid when it is oxygenated. This unique physiology reflects evolutionary adaptation to their low-oxygen coastal habitats and is shared with some other invertebrates such as octopuses, squids, and certain spiders, which also use hemocyanin for oxygen transport.

What makes horseshoe crab blood even more remarkable is its role in immune defense and its critical use in modern medicine. Horseshoe blood contains specialized cells called amebocytes, which are functionally analogous to white-blood-cell defenses in humans. When these amebocytes encounter bacterial toxins — particularly dangerous molecules called endotoxins — they trigger an immediate clotting reaction that encapsulates and neutralizes the threat. Scientists discovered that this reaction could be harnessed as an ultra-sensitive biological test for bacterial contamination in medical products. Extracts of these blood cells, called Limulus Amebocyte Lysate (LAL), are now used worldwide to detect minuscule quantities of endotoxins in vaccines, injectable drugs, surgical implants, and other devices that must be sterile before use. The LAL test can detect endotoxins at levels below one part per trillion, making it the global standard for endotoxin screening in pharmaceuticals and medical equipment.

The importance of the LAL test in healthcare cannot be overstated. Before its development, manufacturers relied on slow and less precise methods, such as injecting products into rabbits and observing fever responses, which took days and raised ethical issues of their own. Since the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) officially adopted the LAL test in the 1970s, it has enabled safer production of vaccines, intravenous therapies, pacemakers, joint replacements, and other devices that sustain millions of lives each year.

Despite its medical value, the practice of harvesting blood from horseshoe crabs has generated significant ethical and environmental concerns. To produce LAL, biomedical companies typically collect wild horseshoe crabs and extract up to about 30 % of their blood before returning them to the ocean. Although industry representatives assert that most individuals survive the process, studies and conservation groups report that a notable percentage — approximately 10 – 15 % — of bled crabs die following blood extraction due to stress, injury, or increased vulnerability to predators and disease.

The impact extends beyond individual crabs. Horseshoe crabs are a keystone species in coastal ecosystems, and their eggs provide critical nourishment for migratory shorebirds like the red knot, a bird listed as threatened under the U.S. Endangered Species Act. Declining horseshoe crab populations have been linked with steep drops in shorebird numbers, illustrating the interconnectedness of species and the ripple effects of unsustainable harvesting.

Responding to these concerns, scientists and conservationists are exploring alternatives to natural horseshoe crab blood. One promising development is recombinant Factor C (rFC), a synthetic compound that imitates the LAL test’s sensitivity without requiring animal blood. The U.S. Pharmacopeia (USP) has recognized rFC as a viable endotoxin test standard, which could reduce pressure on wild horseshoe crab populations if adopted more broadly by pharmaceutical manufacturers. However, legacy products and regulatory hurdles have slowed adoption, meaning that natural LAL remains the dominant method in many parts of the industry.

Other measures aim to make bleeding practices more humane. Updated guidelines encourage gentler handling, reduced exposure to heat and sunlight, and better post-bleeding care to improve survival rates and support population health. Regardless, many researchers and environmental advocates argue that broader implementation of synthetic tests and improved regulatory oversight are necessary to safeguard these ancient animals and the ecosystems that depend on them

In summary, the horseshoe crab’s blue blood is far more than a biological oddity — it is a cornerstone of medical safety testing and a vivid example of how ancient life forms can yield invaluable modern applications. At the same time, its continued use highlights the challenges of balancing scientific advancement with ecological and ethical responsibility, underscoring the need for sustainable alternatives and thoughtful conservation policies.

News in the same category

The reason some seniors decline after moving to nursing homes

Sauna Bathing and Long-Term Cardiovascular Health: Evidence from a Finnish Cohort Study

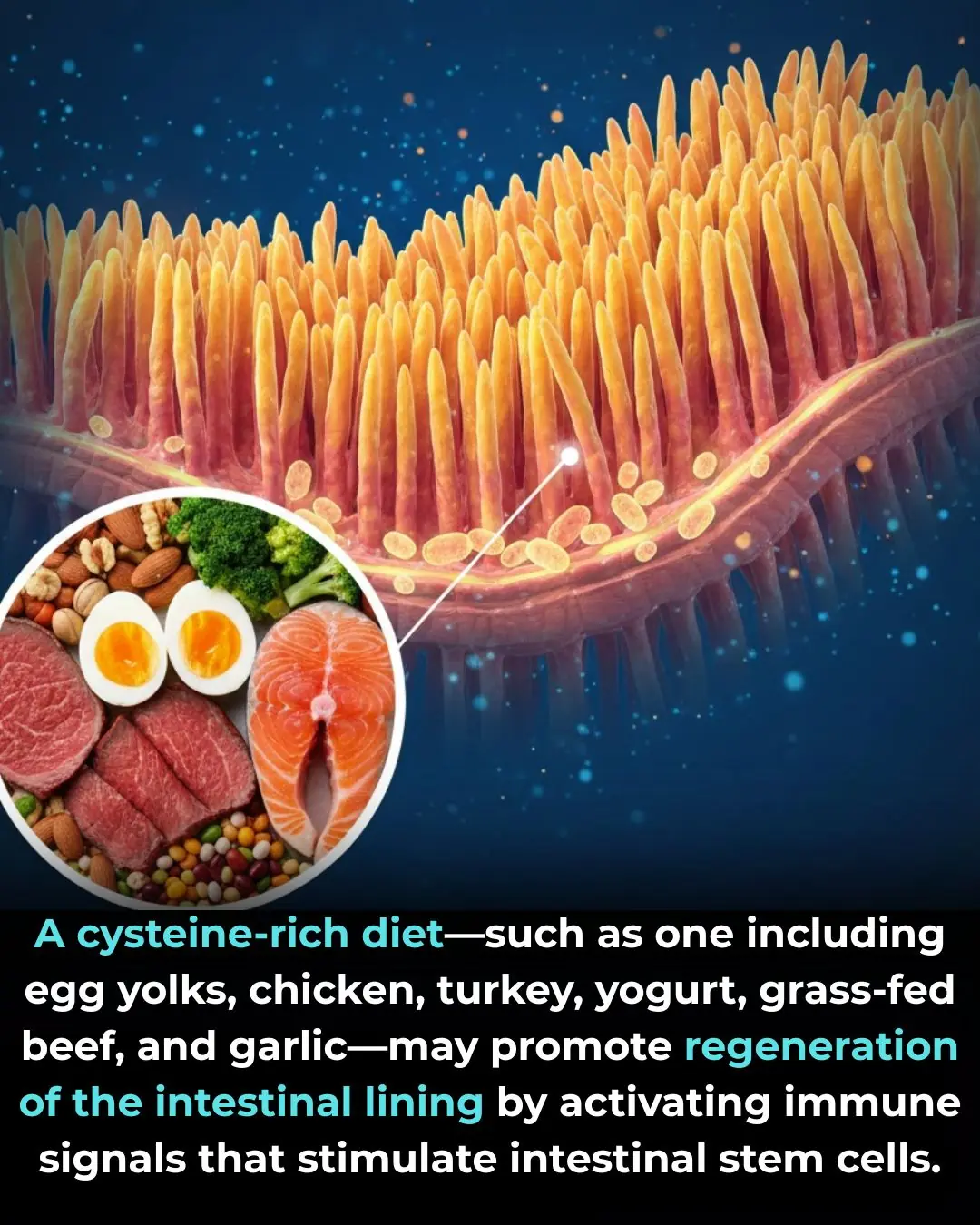

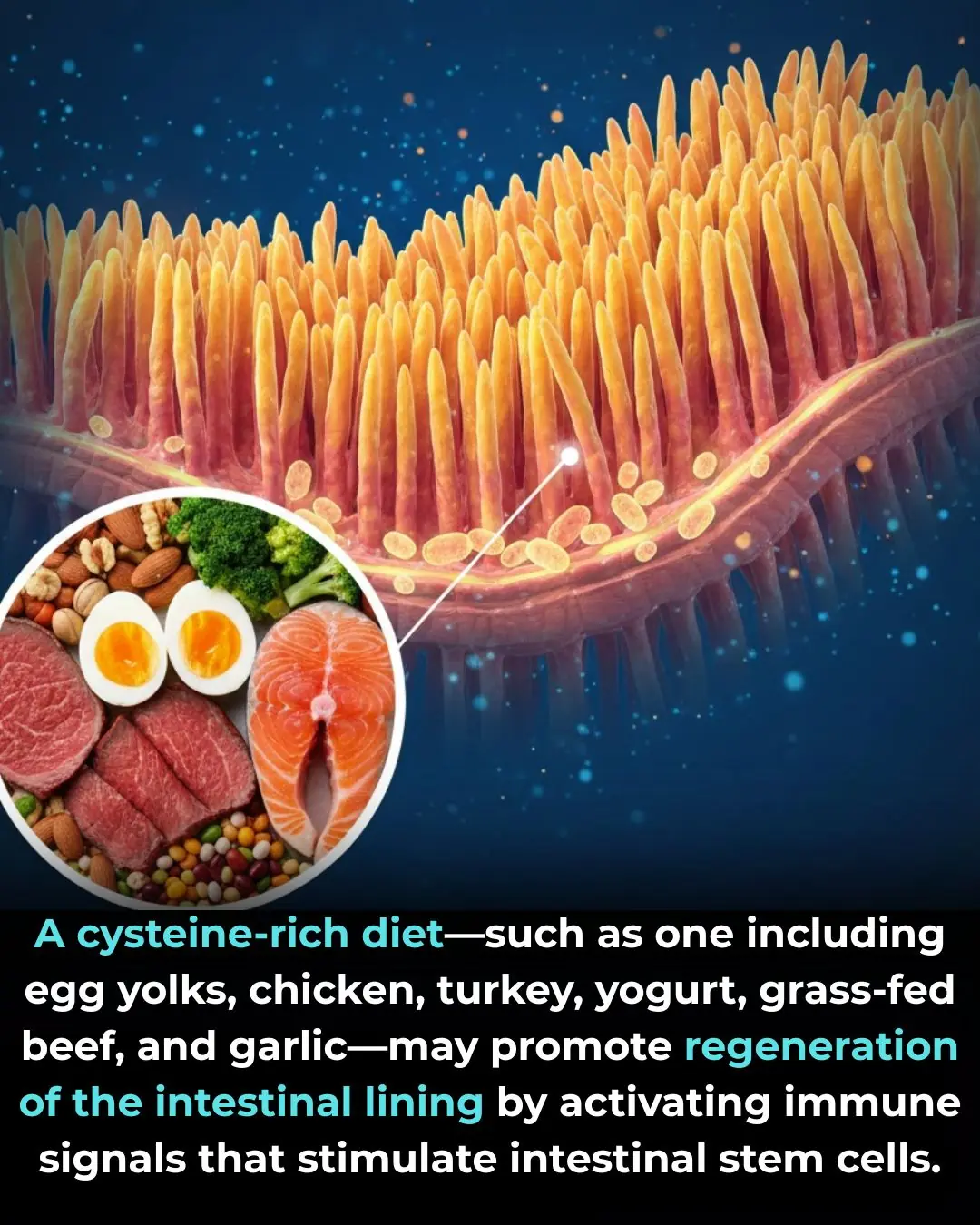

The Role of Dietary Cysteine in Intestinal Repair and Regeneration

Researchers found that 6-gingerol, the main bioactive compound in ginger root, can specifically stop the growth of colon cancer cells while leaving normal colon cells unharmed in lab tests

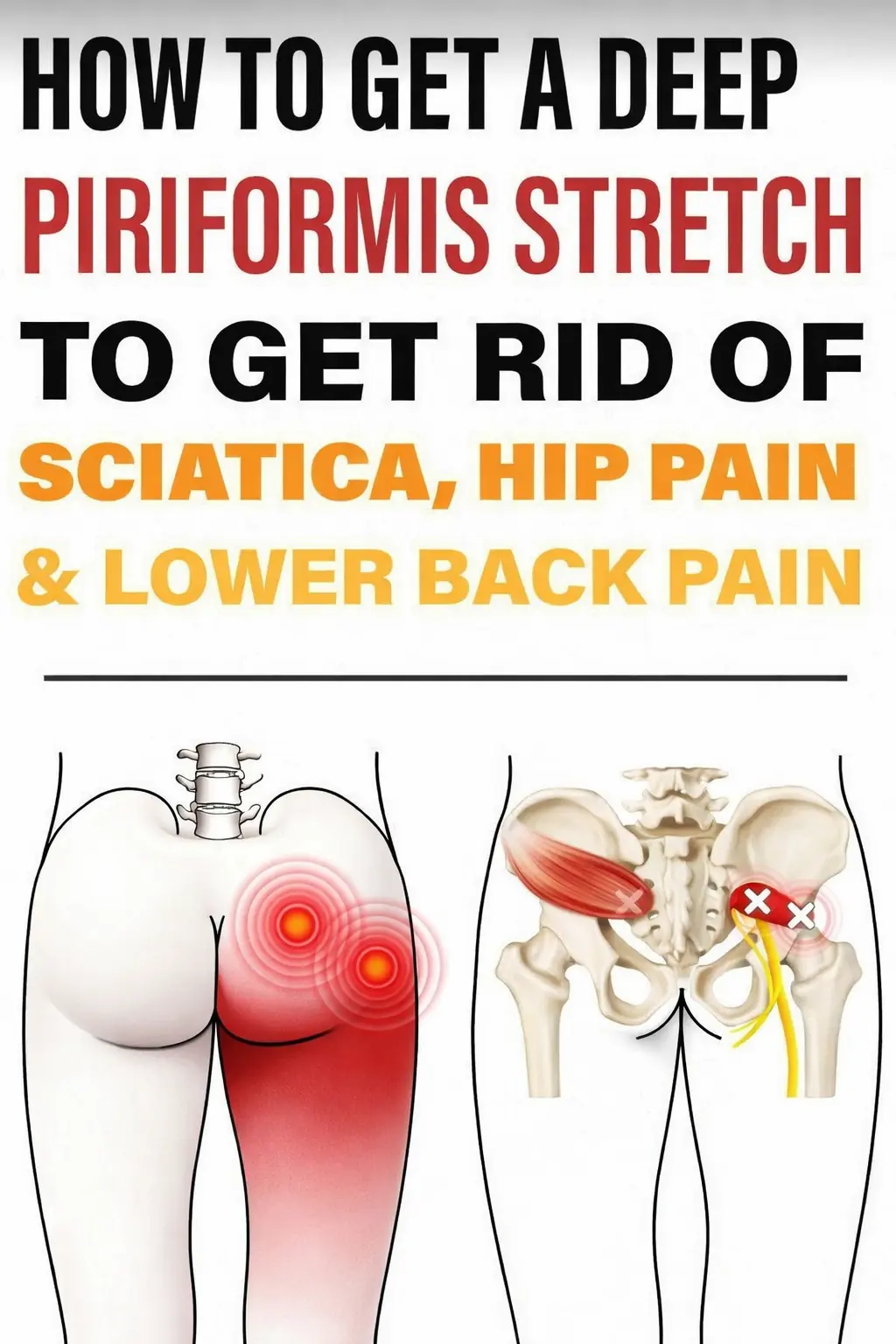

Powerful Piriformis Stretch to Soothe Sciatic, Hip, and Lower Back Pain

Napping During The Day Seriously Affects Brain Aging

Waking at 3 AM every night? 4 hidden causes

Waking at 3 AM every night? 4 hidden causes

Sudden confusion or difficulty speaking: when it’s more than just fatigue

The Four Best Times to Drink Coffee for Maximum Health Benefits

7 Tips to Give Your Evening Routine a Refresh

Your Butt May Reveal Your Diabetes Risk

Doctor, 30, died seven months after cancer diagnosis following unusual symptom

After the age of 70, never let anyone do this to you

Support Joint Health Naturally

The Most Dangerous Time to Sleep

Doctor Shares Three Warning Signs That May Appear Days Before a Stroke

A Couple Diagnosed with Liver Cancer at the Same Time: When Doctors Opened the Refrigerator, They Were Alarmed and Said, “Throw It Away Immediately!”

News Post

How to grow lemons in pots for abundant fruit all year round, more than enough for the whole family to eat

Regularly using these three types of cooking oil can lead to liver cancer without you even realizing it.

6 tips for using beer as a hair mask or shampoo to make hair shiny, dark, and reduce hair loss

When rendering pork fat, don't just put it directly into the pan. Adding this extra step ensures that every batch of pork fat is perfectly white and won't mold even after a long time.

Scientists Crack an “Impossible” Cancer Target With a Promising New Drug

Using an electric kettle to boil water: 9 out of 10 households make this mistake, so remind your family members to correct it soon

4 "cancer culprits" lurking in your home, many people are exposed to daily without knowing it

Three "strange" red spots on the body are actually signs of cancer that very few people notice

5 foot changes that signal liver "exhaustion," a sign that you may have had liver cancer for a long time.

10 types of fruits and vegetables you should never put in the refrigerator; many people don't know this and end up doing it wrong, ruining the taste and causing them to spoil quickly.

You were raised by emotionally manipulative parents if you heard these 8 phrases as a child

The reason some seniors decline after moving to nursing homes

If You Love Being Alone, You Probably Have These 10 Qualities Others Envy

People Who Were Raised By Strict Parents Often Develop These 10 Quiet Habits

Sauna Bathing and Long-Term Cardiovascular Health: Evidence from a Finnish Cohort Study

The Role of Dietary Cysteine in Intestinal Repair and Regeneration

Researchers found that 6-gingerol, the main bioactive compound in ginger root, can specifically stop the growth of colon cancer cells while leaving normal colon cells unharmed in lab tests

Powerful Piriformis Stretch to Soothe Sciatic, Hip, and Lower Back Pain