Reintroduced Wolves Are Helping Baby Aspen Trees Flourish in Northern Yellowstone for the First Time in 80 Years, Study Suggests

Aspen trees are making a long-awaited comeback in Yellowstone National Park, and scientists believe wolves are playing a key role in this recovery. New research suggests that the return of gray wolves—once wiped out from the park—has helped rebalance the ecosystem, allowing young aspens to finally grow tall and healthy after decades of struggle.:focal(3111x1792:3112x1793)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/9e/89/9e89a179-5480-4324-900c-dd78416ca9df/41b34fb4-aad5-4ec6-a58a-2b69b98c1ab8original.jpg)

Gray wolves were reintroduced to Yellowstone in 1995 after being absent for more than 60 years due to hunting, eradication programs, and habitat loss. During their absence, the elk population exploded, peaking at around 17,000 animals in the winter of 1995. With no major predators to control them, elk heavily browsed young aspen shoots, preventing new trees from replacing aging stands. By the 1990s, researchers couldn’t find a single successfully established aspen sapling in some areas of the park.

According to a study published in Forest Ecology and Management, the situation has changed dramatically. Scientists revisited 87 aspen stands in northern Yellowstone that were first surveyed in 2012. When they returned in 2020 and 2021, they found that 43% of those sites now contained young aspens with trunks at least two inches in diameter—something that hadn’t been documented since the 1940s. Even more striking, the density of aspen saplings increased more than 150-fold between 1998 and 2021.

Researchers link this resurgence to the wolves’ impact on elk behavior and numbers. Wolves reduced the elk population to roughly 2,000 wintering individuals and also altered where and how elk graze. With less constant browsing pressure, young aspens finally gained the chance to grow beyond vulnerable heights and become more resilient./https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/29/78/297871bd-ef93-4073-bce3-6d9fa0bd6bb8/3d90402a-9d79-406a-8829-0407ae8b499doriginal.jpg)

The return of aspens doesn’t just benefit the trees themselves. Aspen stands support a wide range of wildlife. Birds like woodpeckers and tree swallows depend on aspen trunks for nesting cavities, while beavers use aspen bark and branches for food and dam-building. Scientists describe this chain reaction as a “trophic cascade,” where changes at the top of the food web ripple downward, influencing plants and animals throughout the ecosystem.

However, the story isn’t entirely settled. Some ecologists caution that Yellowstone’s recovery is still incomplete and influenced by multiple factors. Humans and grizzly bears also reduce elk numbers, while bison populations have grown, placing new pressures on vegetation. A 2024 study noted that ecosystems altered for decades don’t instantly revert to their original state, even after apex predators return.

Still, the reappearance of young aspens marks a hopeful sign. After nearly a century of decline, Yellowstone’s forests are showing visible signs of renewal—suggesting that restoring key predators can set powerful ecological healing processes back in motion.

News in the same category

Israel's Revolutionary Smart Water Pipes Are Turning Water Pressure Into Clean Energy

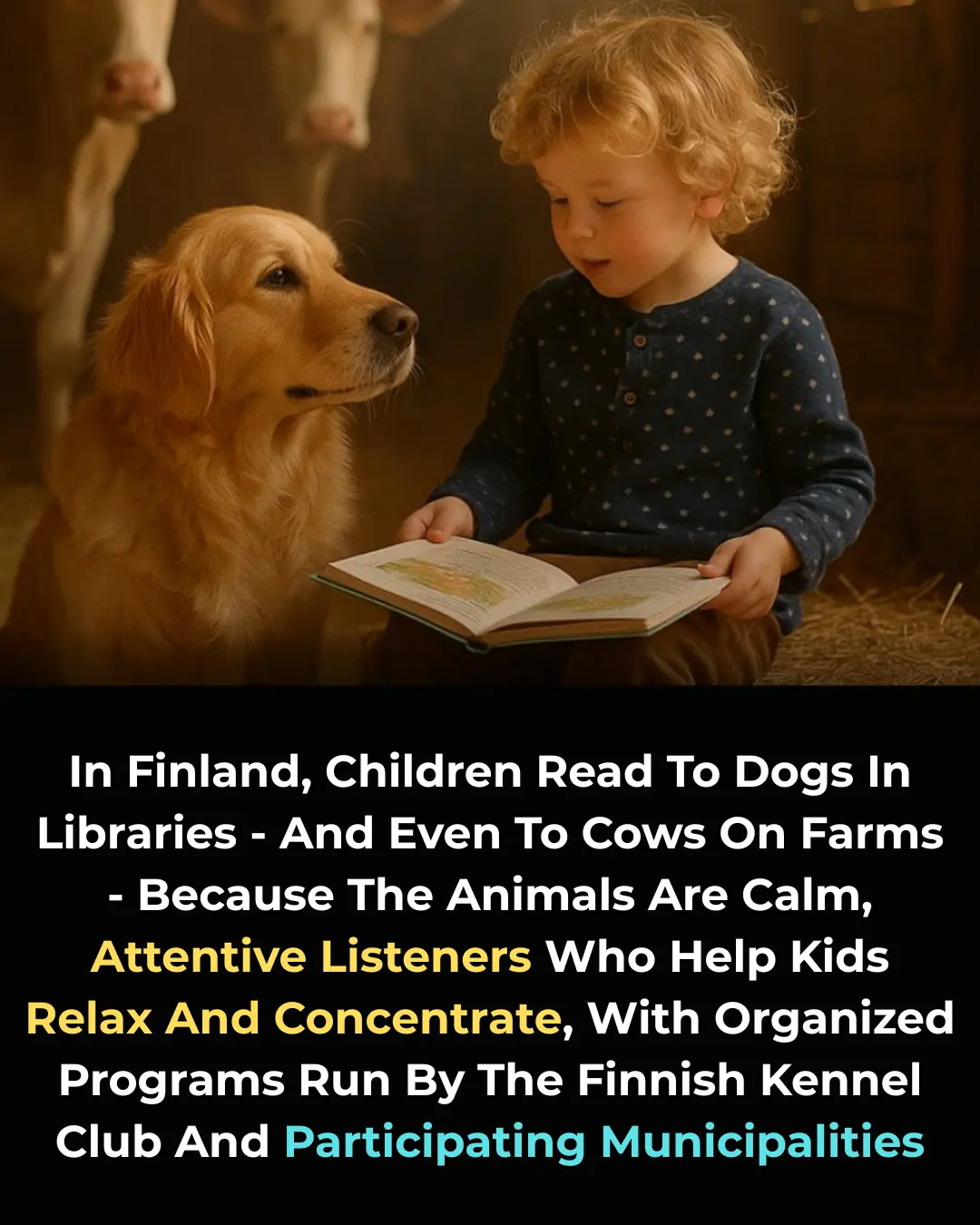

How Reading to Dogs and Cows is Transforming Kids' Confidence and Love for Learning in Finland

Surprising Study Reveals Brain Power Peaks in Your 50s – Here’s What You Need to Know

Ancient Romans Knew the Secret to Self-Healing Concrete – A Discovery That Could Revolutionize Modern Construction

Shocking New Study Reveals CT Scans Could Be Behind 5% of Annual Cancer Cases!

This 3,200-Year-Old Tree Is So Big, It’s Never Been Captured In A Single Photograph…

Why Some Ice Cubes Are Crystal Clear While Others Turn Cloudy

Jessica Cox: The World’s First Licensed Armless Pilot and Her Journey to Inspire the Impossible

How Carmel, Indiana Transformed Its Streets with Roundabouts, Boosting Safety, Reducing Costs, and Cutting Emissions

China Discovers the First Plant Capable of Forming Rare-Earth Minerals Inside Its Tissues

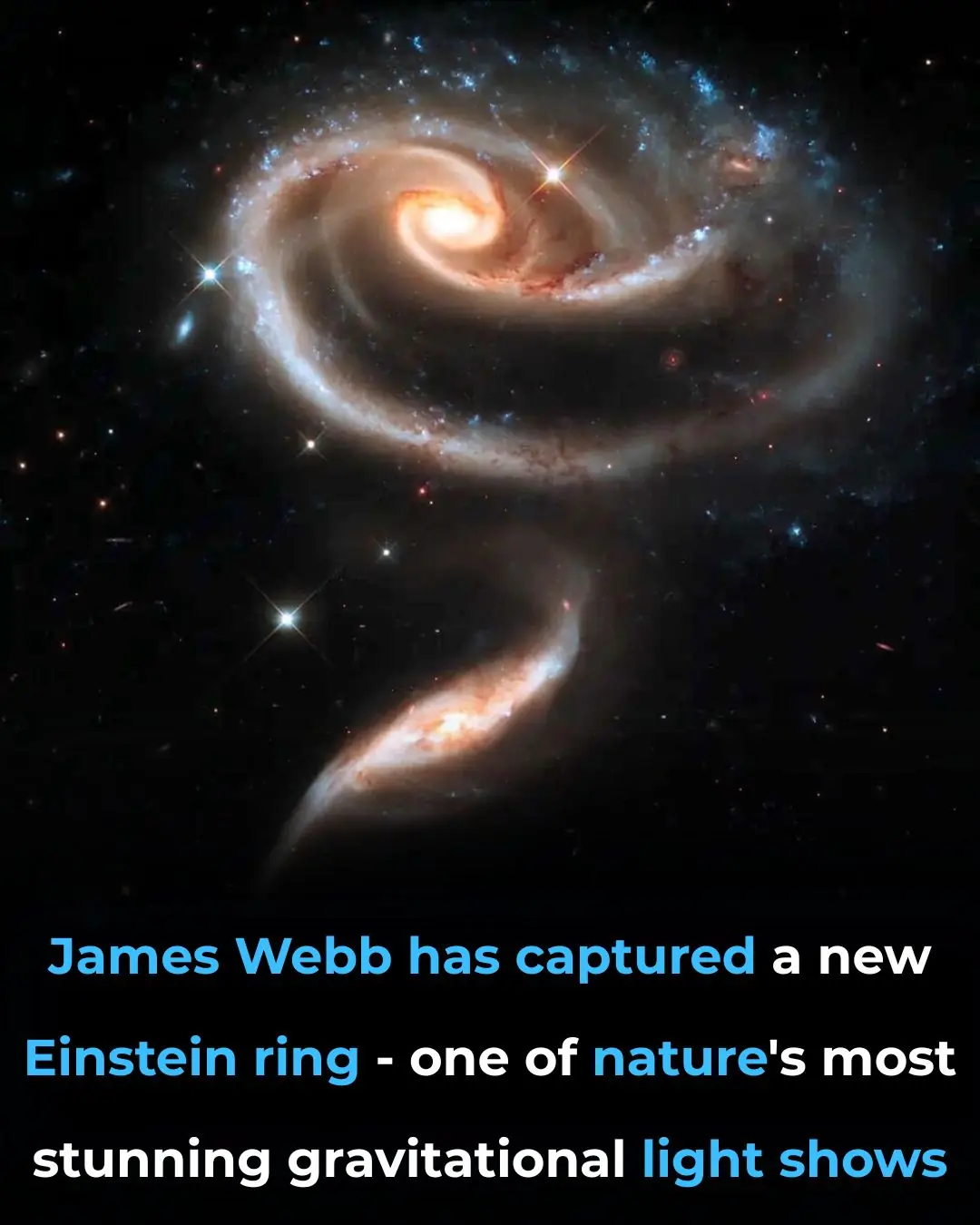

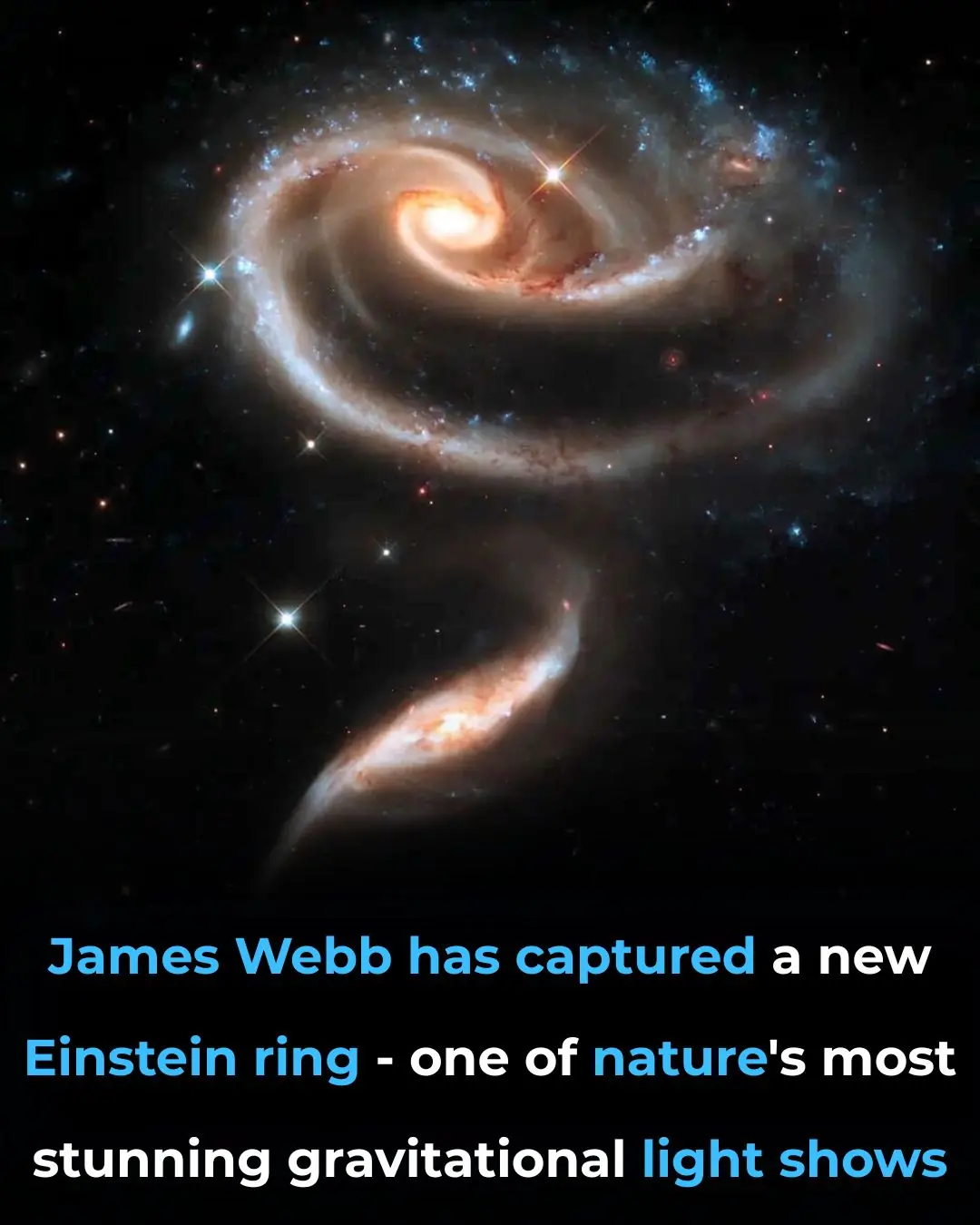

James Webb Telescope Captures Stunning Einstein Ring, Unlocking Secrets of the Early Universe

Groundbreaking Cell Therapy Offers New Hope for Spinal Cord Injury Recovery

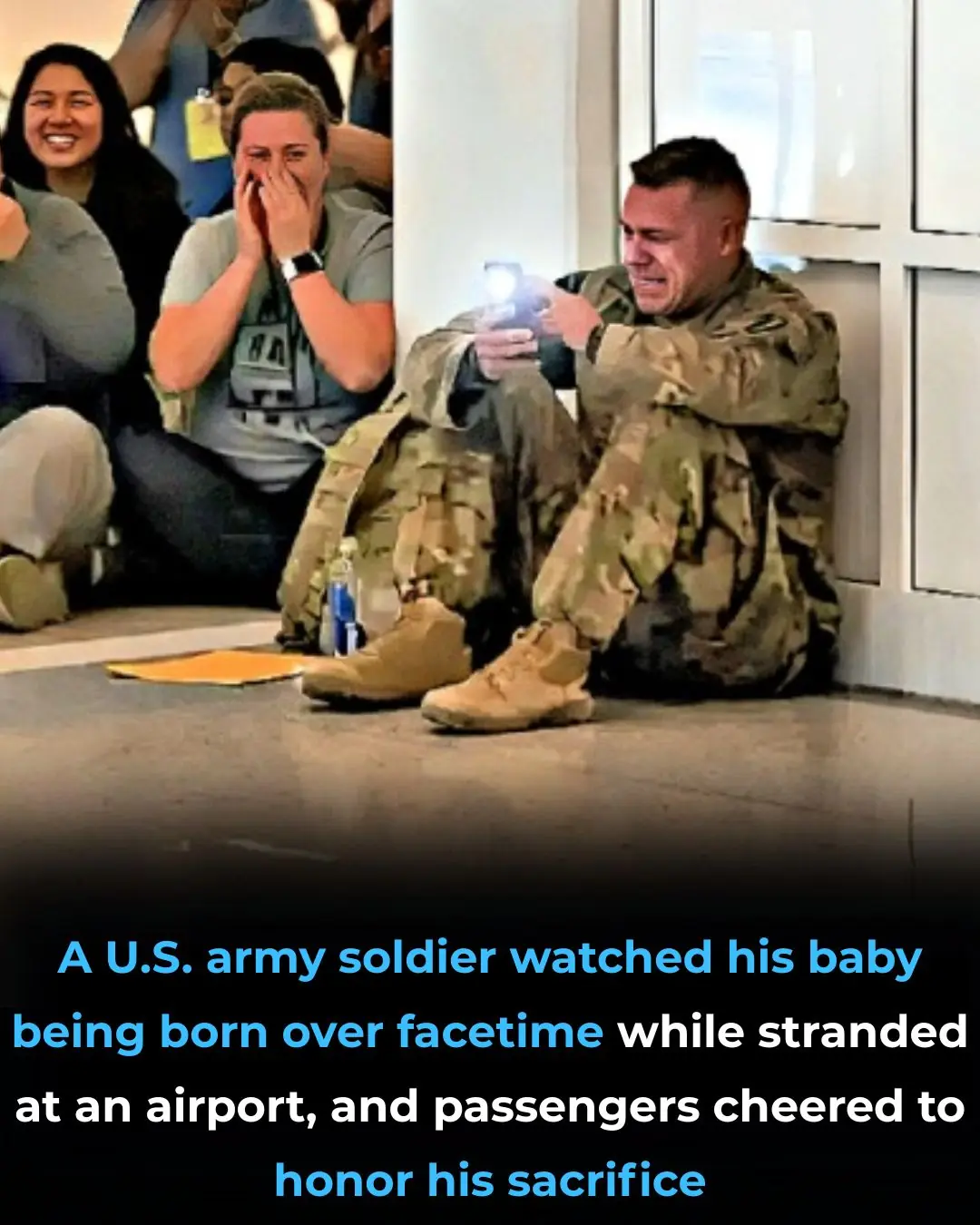

A Soldier’s Heartfelt Moment: A Birth Across Distance and Strangers’ Applause

Japan's Groundbreaking Tsunami Wall Combines Engineering and Environmental Resilience

Revolutionary Contact Lenses with Night Vision Unveiled by Japanese Researchers

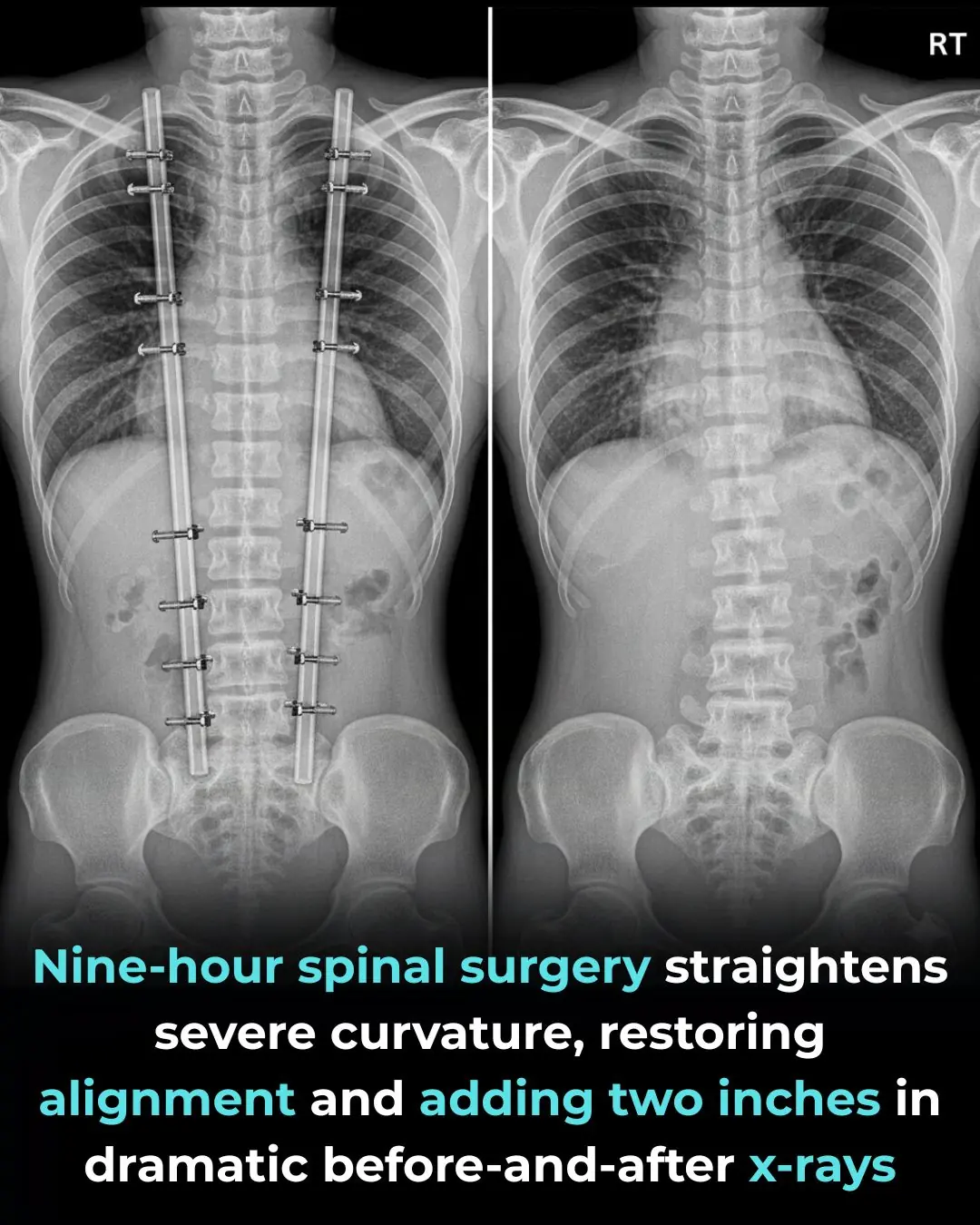

A Life-Changing Spinal Surgery Restores Health and Confidence

The Lost Human Species: A Glimpse Into Our Shared Past

The Swedish Oak Forest: A Symbol of Foresight and the Unpredictability of Progress

News Post

Surprising Discovery: The Appendix Is Not Useless After All – It Plays a Key Role in Gut Health!

Israel's Revolutionary Smart Water Pipes Are Turning Water Pressure Into Clean Energy

How Reading to Dogs and Cows is Transforming Kids' Confidence and Love for Learning in Finland

Surprising Study Reveals Brain Power Peaks in Your 50s – Here’s What You Need to Know

Ancient Romans Knew the Secret to Self-Healing Concrete – A Discovery That Could Revolutionize Modern Construction

Shocking New Study Reveals CT Scans Could Be Behind 5% of Annual Cancer Cases!

This 3,200-Year-Old Tree Is So Big, It’s Never Been Captured In A Single Photograph…

My Daughter’s Lookalike Neighbor Sparked Cheating Fears, But the Truth Was Worse

The natural ingredient that helps you sleep through the night and boosts fat burning

Why Some Ice Cubes Are Crystal Clear While Others Turn Cloudy

The Vitamin The Body Lacks When Legs And Bones Are Painful

Two Teens Mock Poor Old Lady On Bus

8 Warning Signs of Ovarian Cancer Women Should Never Ignore

The Hidden Causes of Bloating — And the Fastest Way to Fix It Naturally

No Man Should Die From Prostate Cancer: The Natural Remedy Every Man Should Know

Jessica Cox: The World’s First Licensed Armless Pilot and Her Journey to Inspire the Impossible

How Carmel, Indiana Transformed Its Streets with Roundabouts, Boosting Safety, Reducing Costs, and Cutting Emissions

China Discovers the First Plant Capable of Forming Rare-Earth Minerals Inside Its Tissues