San Francisco Establishes Reparations Fund Framework to Address Historical Racial Inequities

San Francisco has taken a significant and controversial step in its ongoing efforts to address racial inequality by formally establishing a legal framework for a proposed Reparations Fund. The ordinance, which was approved earlier this month by the San Francisco Board of Supervisors and signed into law by Democratic Mayor Daniel Lurie just two days before Christmas, lays the groundwork for potential financial restitution to eligible Black residents who were allegedly harmed by historic discrimination and displacement.

Under the ordinance, qualifying individuals could eventually receive payments of up to $5 million, making it one of the most ambitious reparations-related proposals ever adopted by a major U.S. city. However, city officials stress that the measure does not allocate public funds, authorize immediate payouts, or guarantee that any individual will receive compensation. Instead, it establishes the legal and administrative structure needed should funding become available in the future.

The ordinance represents a continuation of years-long discussions in San Francisco around reparations for Black residents, particularly those impacted by redlining, urban renewal projects, discriminatory housing policies, and disproportionate law enforcement practices. Advocates argue that these policies contributed to the displacement of Black communities and the erosion of generational wealth, especially during the mid-20th century when redevelopment projects reshaped large parts of the city.

Importantly, the Reparations Fund is designed to be financed through non-city sources, including private donations, philanthropic foundations, grants, and other external funding mechanisms. City leaders have emphasized that taxpayer money is not currently earmarked for the program, a point that has been highlighted amid public debate and political scrutiny. Supporters see this funding model as a way to advance restorative justice without placing additional strain on municipal budgets, while critics question whether sufficient private funding will ever materialize to support such large potential payments.

The ordinance also does not finalize eligibility criteria. Instead, it allows for future policy development to determine who qualifies, how claims would be assessed, and what forms reparations might take beyond direct payments. While monetary compensation has drawn the most attention, earlier reparations proposals in San Francisco have included housing assistance, business grants, debt relief, and access to education and health services.

Reactions to the measure have been sharply divided. Supporters view it as a historic acknowledgment of systemic racism and a moral obligation to repair long-standing harms. Opponents argue that the proposal raises legal, ethical, and practical concerns, including questions about fairness, feasibility, and the role of local governments in addressing historical injustices.

Nationally, San Francisco’s move places it at the forefront of a broader conversation about reparations in the United States. While no federal reparations program currently exists, cities such as Evanston, Illinois, and states like California have explored or implemented limited forms of reparative policies. San Francisco’s ordinance, though largely symbolic at this stage, may influence how other jurisdictions approach similar initiatives.

As the Reparations Fund moves from concept to potential implementation, its future will depend heavily on funding availability, legal challenges, and public support. For now, the ordinance stands as a framework—one that signals intent and recognition, but leaves many critical questions unanswered.

News in the same category

Bun B Expands Trill Burgers with New Missouri City Location

Octavia Spencer celebrates 'iconic' Sinners' duo Ryan Coogler and Michael B. Jordan for EW's 2025 Entertainers of the Year

Lil Durk's Legal Team Alleges He's Spent 131 Days in Solitary Confinement Over Apple Watch

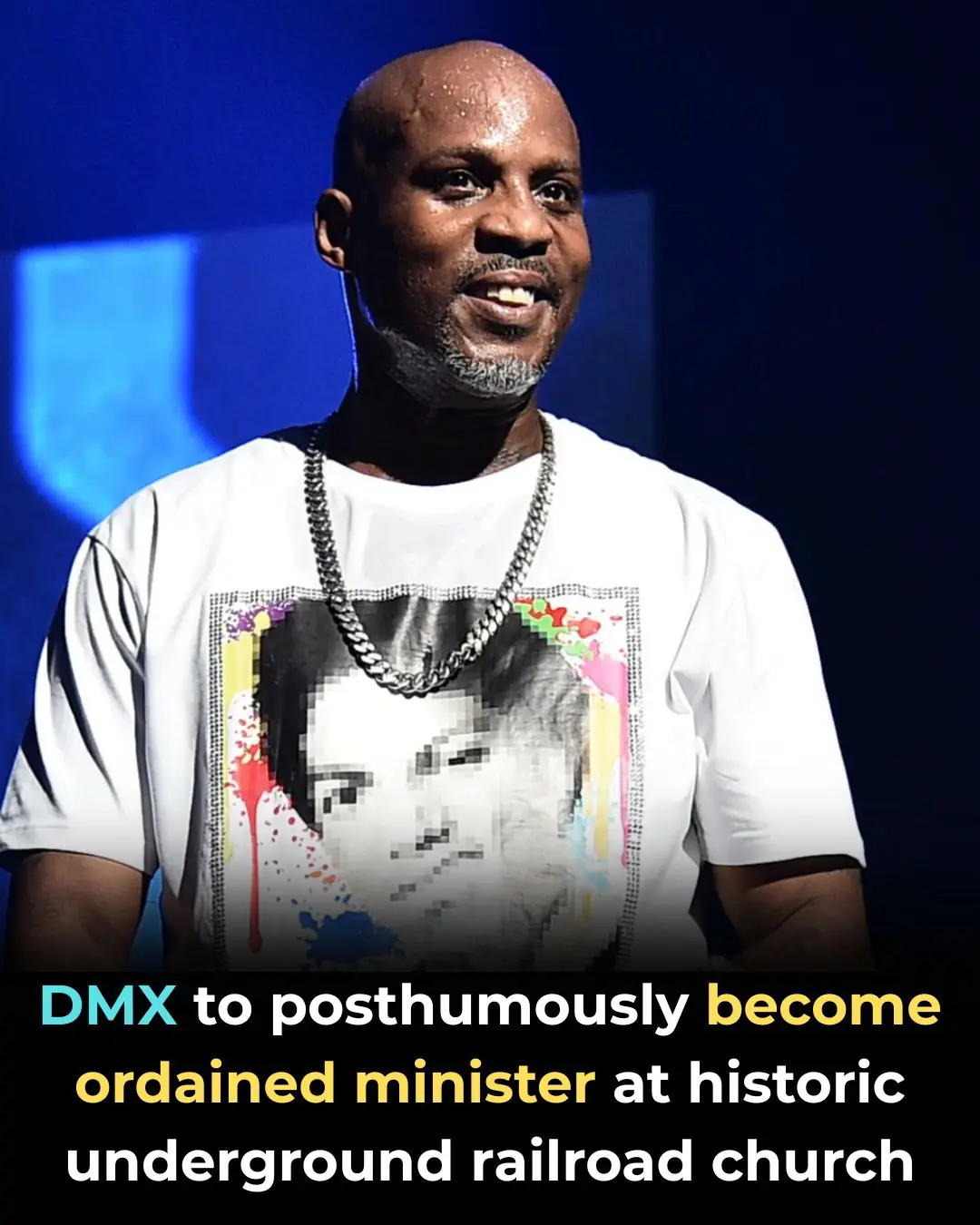

DMX Will Posthumously Become Ordained Minister at Historic Underground Railroad Church

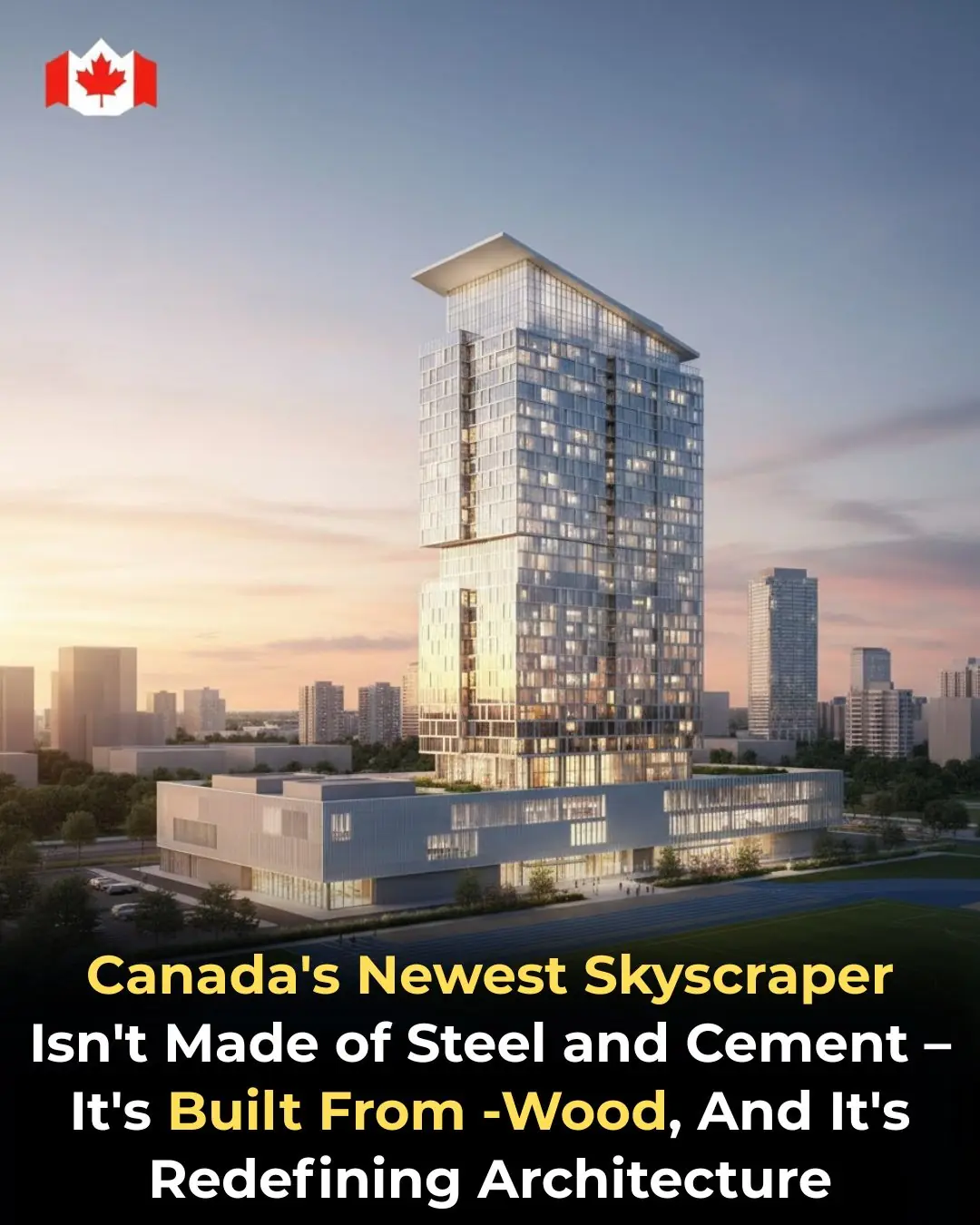

Canada Builds the Future in Wood: Inside Toronto’s Groundbreaking Timber Skyscraper

The Woman Who Refused to Quit: How Jacklyn Bezos Changed Her Life—and Helped Shape the Future of the World

From Prison Food to Fine Dining: How Lobster Became a Luxury in America

Michael B. Jordan Opens Up to David Letterman About His Future: ‘I Want Children’

Marlon Wayans Clarifies He Never Defended Diddy During His 50 Cent Rant

Snoop Dogg Becomes Team USA’s First Honorary Coach for 2026 Olympic Winter Games

Jason Collins announces he is battling stage 4 brain cancer: 'I'm going to fight it'

Kevin Hart Inks Licensing Deal for His Name

Michael B. Jordan Wanted to Change His Name Because of the Other Michael Jordan

Stranger Things fans have bizarre theory over final episode and everyone's saying the same thing

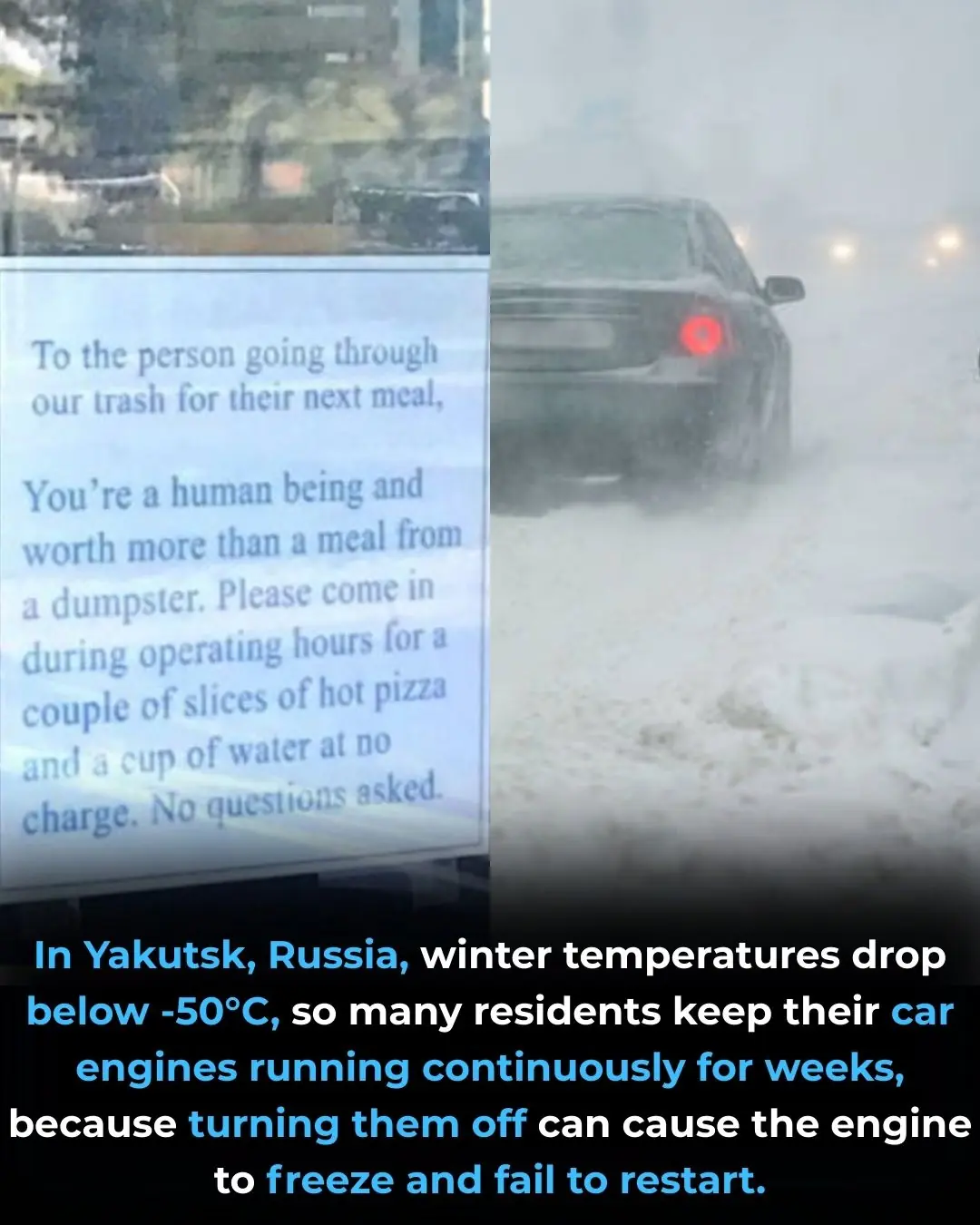

In Yakutsk, Winter Is So Cold People Never Turn Off Their Cars

Florida Officially Recognizes Gold and Silver as Legal Currency Starting July 2026

JFK's grandson Jack Schlossberg shares emotional tribute to sister Tatiana after her death from cancer aged 35

News Post

Jeezy Calls Out Industry for Exploiting Trauma in Young Rappers

Marlon Wayans warns 50 Cent

Bun B Expands Trill Burgers with New Missouri City Location

Octavia Spencer celebrates 'iconic' Sinners' duo Ryan Coogler and Michael B. Jordan for EW's 2025 Entertainers of the Year

Lil Durk's Legal Team Alleges He's Spent 131 Days in Solitary Confinement Over Apple Watch

DMX Will Posthumously Become Ordained Minister at Historic Underground Railroad Church

How Guava Can Naturally Support Your Eye Health: Surprising Benefits and Safe Remedies

Grape Hyacinth (Muscari): A Tiny Spring Wonder with Surprising Benefits and Uses

12 Surprising Benefits of Bull Thistle Root (And Safe Ways to Use It Naturally)

14 Little-Known Health Benefits of Moringa Leaves

Tips for preserving bean sprouts to keep them crispy and prevent them from turning black for 7 days.

Simple Tips to Store Ginger Without a Refrigerator: Keep It Fresh for a Year Without Sprouting or Spoiling

Frozen Meat Rock-Hard from the Freezer? Use These Two Simple Methods to Thaw It Quickly Without Waiting

5 Types of Eggs That Can Be Harmful If Consumed Too Often

Women Who Drink Perilla Leaf Water With Lemon at These 3 Times May Notice Brighter Skin and a Slimmer Waist

Tata Sierra vs Mahindra XUV 7XO: A Mid‑Size SUV Showdown 🚙🔥

This red, scaly patch won’t go away. It's all over my forehead and doctor isn't answering me. What is it?

I keep wondering why this happens to me

The Impressive Health Benefits of Guava Fruit and Leaves & How to Eat Guava (Evidence Based)