The Science of Rare Steak Versus Rare Chicken

There’s a fascinating little paradox on the dinner table: one type of meat is praised for being served pink—almost bloody—in the center, while another inspires instant panic if it’s anything less than fully cooked. A ruby-red steak, dripping with savory juices, is celebrated as the ultimate symbol of indulgence and culinary confidence. But a slightly pink chicken breast? Just the thought is enough to make most people push their plate away.

This contrast isn’t just about culture or preference. It’s rooted in biology, microbiology, cooking science, and centuries of culinary trial-and-error around the world. When we explore these layers more closely, we discover why a blush of red can be an invitation in one dish yet a warning in another. Understanding these differences not only helps us enjoy food more confidently but also reminds us how thin the line can be between pleasure and microbial danger.

The Biology Behind the Difference

At the core of the rare-steak-versus-rare-chicken debate lies biology—specifically, the structure of muscle tissues and the behavior of bacteria.

Beef muscle fibers are dense and tightly packed. This natural density acts like a shield, preventing bacteria from burrowing deep inside the meat. When cows are slaughtered and processed correctly, the interior of a beef steak remains virtually sterile. Harmful microbes like E. coli tend to remain on the outer surface. Once the steak meets a blistering-hot pan or grill, that searing heat destroys the surface bacteria, making the interior safe to eat even when cooked rare, tender, and juicy.

Chicken is fundamentally different. Its muscle fibers are far more porous, with looser structure and more pathways for bacteria to enter. Pathogens such as Salmonella and Campylobacter don’t simply cling to the exterior—they frequently infiltrate the interior tissues. This means that even if the outside of a chicken breast is perfectly charred, the inside may still harbor dangerous bacteria unless it reaches a safe internal temperature. That’s why public health guidelines insist on cooking poultry to 165°F (74°C).

Pathogens at Play

The microorganisms behind foodborne illness are tiny, but their consequences can be severe. Different meats host different bacterial threats, and how deeply those pathogens penetrate the flesh determines how safely the meat can be eaten.

E. coli in beef.

Certain strains—especially O157:H7—can cause severe gastrointestinal illness and potentially life-threatening complications. Fortunately, in whole cuts of beef, these bacteria remain on the surface, where high heat kills them instantly.

Salmonella in chicken.

Salmonella infects about a million Americans each year. It spreads easily throughout chicken muscle tissue, causing fever, diarrhea, and cramps. Vulnerable individuals, like children or the elderly, are at even greater risk.

Campylobacter in chicken.

This pathogen often leads to bloody diarrhea and, in some cases, can trigger Guillain–Barré syndrome, a serious neurological disorder that can cause temporary paralysis.

Other pathogens.

Chicken can also harbor Clostridium perfringens, a common cause of food poisoning. Beef is generally safer in whole cuts, but once it is ground, its risk level rises dramatically.

Taken together, these pathogens make pink beef and pink chicken two entirely different realities. In beef, the redness is often nothing more than myoglobin-rich juices; in chicken, it can be a sign of unsafe cooking.

Ground Meat: A Special and Risky Case

When beef is ground, the formerly sterile interior becomes exposed to any bacteria present on the surface. Grinding distributes those microbes throughout the mixture. As a result, the center of a burger can be just as contaminated as the outside. Searing the surface isn’t enough.

This is why food safety guidelines require ground beef to be cooked to 160°F (71°C). Many outbreaks of E. coli trace back to burgers, not steaks. Industrial processing makes the risk worse: contamination in one cut of meat can end up mixed into hundreds of pounds of ground beef.

Ground chicken and turkey are even riskier because poultry already harbors pathogens inside the muscle. A rare chicken burger is never safe under any typical conditions.

Cooking Science: Temperature, Time, and Technique

Cooking is both a craft and a scientific process. Heat transforms flavor while simultaneously neutralizing harmful pathogens.

-

Steak (whole cuts): Safe at 145°F (63°C) with a rest period. Many enthusiasts enjoy medium-rare steak at 130°F (54°C) because the interior is naturally sterile.

-

Ground beef: Must reach 160°F (71°C) due to internal contamination risks.

-

Chicken (all cuts): Must reach 165°F (74°C). There is no safe rare or medium version of chicken.

-

Sous-vide exception: Precise, low-temperature cooking can pasteurize meat if held long enough. Chicken, for example, can be pasteurized at 150°F (65°C), but only with strict time control and professional-level vigilance.

One key lesson: color is not a reliable indicator of doneness. Some chicken remains pink even when fully safe, and some beef turns brown before reaching safe temperatures. A digital thermometer is the most reliable tool in any kitchen.

Cultural Memory and Culinary Tradition

Across cultures and centuries, humans have developed cooking habits rooted in survival. The rules we follow today often evolved from painful experiences with illness long before we understood the microbiology behind them.

Beef traditions.

Many global cuisines celebrate lightly cooked or raw beef: French steak tartare, Japanese gyu tataki, Italian carpaccio. These dishes emerged because beef’s structure allowed safe experimentation with minimal cooking.

Chicken traditions.

By contrast, chicken has been universally cooked through. Whether it’s Indian tandoori, American fried chicken, Mexican pollo asado, or Chinese soy sauce chicken, cultures around the world learned—through illness—that undercooked poultry was dangerous.

Rare exceptions.

Japan’s torisashi (raw chicken sashimi) exists, but it is controversial and heavily regulated. Even in Japan, health authorities warn against it due to recurring outbreaks.

These culinary norms function like collective memory. Our ancestors didn’t know the words Salmonella or Campylobacter, but they learned through generations of experience that undercooked chicken was risky while rare beef could be enjoyed safely.

The Invisible Danger Zone: Cross-Contamination

Even if you cook chicken properly, the raw juices can create hazards long before the food reaches the pan.

-

A single drop of raw chicken juice can contaminate cutting boards, vegetables, or bread.

-

Washing raw chicken—once common advice—actually spreads bacteria via splashing water.

-

Knives, hands, and countertops easily become carriers for pathogens.

To reduce risks:

-

Store chicken on the bottom fridge shelf.

-

Use separate cutting boards for raw meat and produce.

-

Wash hands thoroughly with warm soapy water for at least 20 seconds.

-

Disinfect counters, sinks, and utensils after raw poultry contact.

Many foodborne illnesses stem from cross-contamination rather than undercooking, making kitchen hygiene just as important as temperature control.

Making Well-Cooked Chicken Delicious

Some people complain that fully cooked chicken tastes dry or bland, but proper techniques can make chicken both safe and spectacular.

-

Brining: Saltwater solutions help chicken retain moisture.

-

Marinating: Acids and dairy tenderize meat while adding layers of flavor.

-

Frying or breading: Coatings trap moisture and create crisp, flavorful exteriors.

-

Sous-vide cooking: Allows precise, juicy chicken even at lower temperatures while ensuring safety.

-

Resting: Letting chicken rest after cooking redistributes juices for better texture.

With the right methods, chicken cooked to safe temperatures can be succulent, aromatic, and richly satisfying.

Flavor, Safety, and the Balance Between Them

A rare steak and a rare chicken breast might look superficially similar, but their food safety profiles couldn’t be more different. Steak’s dense muscle structure keeps dangerous bacteria on the surface, where they’re easily eliminated. Chicken’s porous fibers and common internal pathogens mean the danger runs deep, requiring thorough cooking every time.

Ultimately, the contrast between rare beef and rare chicken tells a broader story about how biology informs culture, how pathogens influence cuisine, and how science clarifies instincts developed over generations. Our ability to savor a rare steak isn’t recklessness—it’s a calculated choice backed by anatomical and microbiological realities. And our caution with chicken? That’s a centuries-old rule supported by modern food science.

News in the same category

Panic Attacks And Anxiety Linked To Low Vitamin B6 And Iron levels

Scientists Discovered How to Kill Prostate Cancer Cells Without Harming Healthy Tissue — Here’s the Breakthrough

The effortless daily trick people use to double their potassium

Government Set to Phase Out Animal Testing and Replace It With Controversial Alternative

12 Early Warning Signs of Dementia You Shouldn’t Ignore

This Old-School Home Remedy Could Ease Back, Joint & Knee Pain in Just 7 Day

The Daily Drink That Helps Clear Blocked Arteries Naturally

8 Warning Signs of Colon Cancer You Should Never Ignore

Study: nearly all heart attacks and strokes linked to 4 preventable factors

Stop adding butter — eat these 3 foods instead for faster weight loss

How Water Fasting Regenerates The Immunity, Slows Down Aging And Lowers The Risk Of Heart Attacks

Better Than Medicine? The Shocking Truth About Dates & Blood Sugar!

Take lemon and garlic on an empty stomach for 7 days — unclog your arteries

Knee Cartilage Crisis? 7 Foods That Rebuild Cushion, Crush Pain, and Restore Strides in 30 Days

Banana Peels: The Kitchen Scrap That Banishes Gray Hair Forever

He thought it was just an allergy, until the diagnosis proved otherwise

3 Powerful Drinks to Keep Your Legs Strong, Steady, and Full of Life

The Best Ways to Lower Blood Sugar Fast: What Science Really Says

News Post

A Forgotten Car’s Journey: Rediscovered, Remembered, and Recycled

Revolutionary Gel from Germany Offers Non-Surgical Solution for Cartilage Regeneration

From Playground to Graduation: The Enduring Power of Childhood Friendship

The Spruce Pets – Creative ways to feature cats and dogs in weddings.

The Water Man of Tsavo: A Hero's Mission to Save Wildlife from Drought

There are two round holes on the plug, and their magical use is little known.

Better Sleep, Healthier Spine: Why You Should Avoid Stomach Sleeping

Plumbing Mayhem on Brown Friday: How Holiday Feasts Overload Pipes

Don’t Pour Hot Water Into a Clogged Sink — Do This Instead for a Quick Fix and Fresh Smell

Rare Orange Shark With Ghostly White Eyes Captured in First-of-Its-Kind Sighting

Health Alert: Contaminated DermaRite Products Recalled Across U.S. and Puerto Rico

Panic Attacks And Anxiety Linked To Low Vitamin B6 And Iron levels

Into the Darkness: A Bioluminescent Jellyfish Illuminates the Deep Ocean

Scientists Discovered How to Kill Prostate Cancer Cells Without Harming Healthy Tissue — Here’s the Breakthrough

The effortless daily trick people use to double their potassium

Germany’s 95% Renewable Power Day: Progress, Challenges, and Lessons for the Future

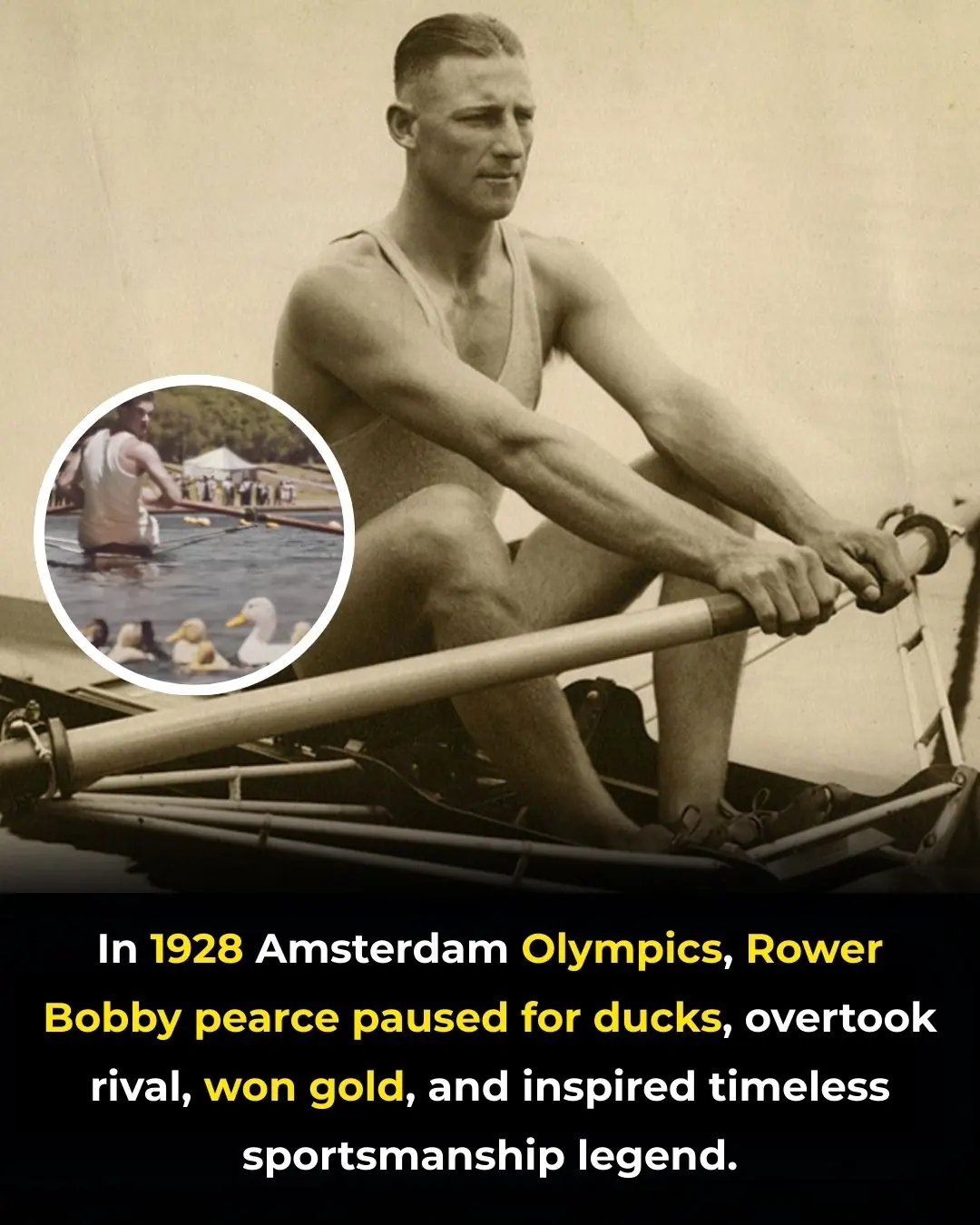

The Rower Who Chose Humanity: How Bobby Pearce Made History in Amsterdam 1928

Government Set to Phase Out Animal Testing and Replace It With Controversial Alternative