The UK Has Created a Robot Fish That Eats Ocean Plastic and Powers Itself by Digesting It, Eliminating the Need for a Battery

Oceans, Plastic, and the Machines That Could Help Save Them

The ocean has always been both a provider and a mirror — giving us food, oxygen, and beauty, while reflecting the choices we make on land. In recent decades, however, that reflection has grown cloudier, blurred by an ever-rising tide of plastic waste. Once celebrated as a miracle material, plastic now saturates every marine habitat, breaking down into microscopic fragments that slip through filters, evade cleanup, and infiltrate the bodies of sea creatures and humans alike.

The problem is no longer limited to bottles bobbing in waves or fishing nets tangled on reefs. It has become a diffuse, nearly invisible threat, embedded in the very systems that sustain life on Earth. Addressing it will take more than beach cleanups or municipal recycling drives. It requires a transformation in our approach — not as a fight against nature, but as a collaboration with it.

Around the globe, scientists and engineers are turning to biomimicry, studying how organisms move, heal, and survive, then translating those lessons into technology. In the United Kingdom, that philosophy has inspired an extraordinary creation: a robotic fish that powers itself by digesting the very microplastics it collects — eliminating the need for batteries and running on the pollutant it is designed to remove.

The Invisible Tide of Microplastics

The plastic problem has evolved from an obvious eyesore into a subtle, insidious crisis. Microplastics — fragments smaller than five millimetres — now contaminate nearly every corner of the marine environment. They drift in open water, sink into deep-sea sediments, embed themselves in Arctic ice, and accumulate in the tissues of marine animals.

Their sources are diverse: the slow decay of packaging, synthetic fibres shed during laundry cycles, particles scraped from car tyres, even microscopic dust from shoe soles rubbing against pavement. As they degrade, plastics leach chemicals like bisphenol A (BPA), phthalates, and heavy metals — substances linked by research to hormonal disruption, inflammation, and cellular damage.

The consequences ripple through entire ecosystems. Fish and shellfish that ingest microplastics often mistake them for food, feeling full without receiving nutrients — a slow path to starvation. Those particles then climb the food chain, from plankton to predators, until they arrive on human plates. In recent years, scientists have even detected microplastics in human lungs, bloodstreams, and placental tissue, prompting urgent questions about long-term health impacts.

Unlike large debris that can be retrieved, microscopic particles are nearly impossible to filter out once they enter marine systems. Prevention, therefore, becomes as crucial as cleanup.

A 2023 study published in PLOS ONE estimated that more than 170 trillion plastic particles now float in the world’s oceans — and the rate of accumulation is accelerating. While striking images of turtles trapped in six-pack rings may spark outrage, the microplastic crisis remains largely invisible, and therefore often ignored, despite its far greater reach.

A Fish That Feeds on Pollution

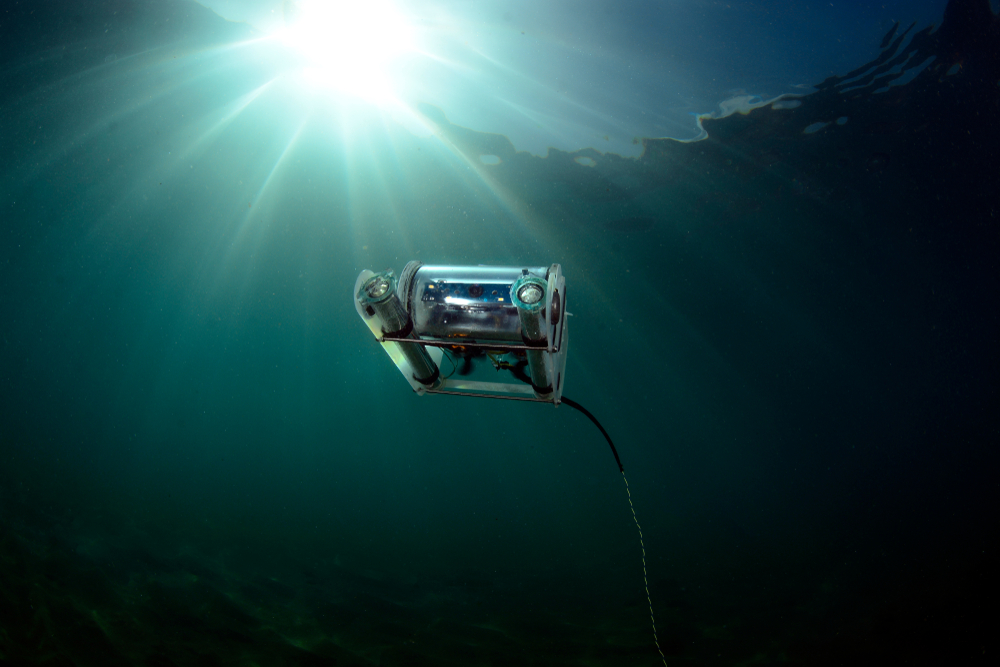

Off the coast of southern England, a new kind of swimmer has joined the waves — born not of flesh and bone, but of ingenuity. Developed by researchers at the University of Surrey, this robotic fish mimics the elegant movements of real fish, propelled by a flexible tail. But it does not hunt for plankton or prey. Its target is microplastics.

What makes the design remarkable is its self-sufficiency. The robot draws in water containing microplastics, filters the particles, and converts them into low-voltage electricity — enough to power its systems. Over a 12-hour patrol, a single unit can collect over two kilograms of microplastics, all without batteries, fossil fuel, or manual intervention.

Constructed from soft, biodegradable materials, it poses no threat to marine life. It swims silently, avoids collisions, and surfaces when its collection chamber is full. The vision isn’t just one fish, but fleets of them — autonomous, cooperative swarms patrolling harbours and coastlines.

This approach exemplifies biomimicry at its finest: designing machines that blend into ecosystems, not disrupt them. If scaled, such fleets could form a global network of ocean-cleaning organisms, working in harmony with the waters they protect.

A Global Wave of Ocean Robotics

The UK’s plastic-digesting robo-fish is just one example in a worldwide surge of marine-cleaning technology.

In China, Sichuan University researchers have developed a robot just 13 millimetres long — smaller than a paperclip — that swims with surprising agility. Its soft body, inspired by the nacre inside clam shells, attracts microplastics via electrostatic and chemical forces. Powered by infrared light, it can self-heal up to 89% of its functionality after damage, making it resilient for long-term deployment.

In South Korea, fish-like robots serve a different mission: protecting aquaculture. The Ichthus V5.5, designed at Imperial College London, glides through fish farms, monitoring water quality and detecting pollutants early. It navigates tight spaces with a turning radius one-tenth of its body length and docks itself for recharging, much like a dolphin surfacing for air.

Across continents, the philosophy is the same: learn from nature, then give back to it.

The Boundaries of Robotic Solutions

For all their promise, these innovations are still in their infancy. The University of Surrey’s model, impressive as it is, can only patrol a limited area. Cleaning an entire bay is one thing; cleansing the vast open ocean is another. True impact will require coordinated fleets, robust navigation, and significant investment.

Durability is also a challenge. The ocean is harsh — saltwater corrodes, storms damage, debris scrapes. Even self-healing materials have limits. And while robots can remove existing waste, they do not stop the torrent of new plastic entering the seas each year. Without systemic change in production, use, and disposal, they risk becoming permanent fixtures rather than temporary aids.

Rethinking Our Plastic Footprint

Plastic itself is not the villain; its misuse is. Originally valued for being strong, light, and versatile, it transformed industries. But when applied to single-use products — used for minutes, persisting for centuries — convenience overshadowed responsibility.

Real solutions require coupling innovation with prevention. Researchers at Rutgers University, for instance, are developing plant-based packaging that decomposes naturally without releasing toxins. Other teams are experimenting with packaging made from food waste or agricultural fibres, designed to fit into a circular economy where materials are reused or safely returned to the environment.

This is not just a matter of personal choice. Governments must legislate against unnecessary plastics, industries must redesign products for longevity and recyclability, and consumers must favour sustainable alternatives. If these shifts take root, robo-fish could remain an emergency measure, not an everyday necessity.

Learning from Nature to Protect It

There is a poetic symmetry in a machine that survives by consuming what harms its living counterparts. The robo-fish is more than a gadget — it’s a reminder that human creativity, when aligned with natural principles, can be restorative instead of exploitative.

But the real lesson is about responsibility. Technology can help repair damage, but it cannot absolve us of the duty to prevent it. The oceans’ fate will hinge not just on our inventions, but on whether we view nature as expendable — or as the foundation of life itself.

The robo-fish stands as both inspiration and warning: proof of what’s possible when we listen to nature, and a call to act before damage becomes irreversible. By combining innovation with restraint, we can write a different future for our oceans — one in which humans and machines work together, not to clean up endless harm, but to ensure it never happens at all.

News in the same category

Trump is Looking to Change Marijuana Laws in the Us and It Could Have a Major Impact

Decode the secrets behind human fingerprints.

Ch!lling simulation shows what actually happens to your body when you d!e

Scientists issue warning for surprising item people use that's 40 times dirtier than a toilet seat

Scientists reveal what your favorite way to eat eggs really says about you

Truth behind 5,000-year-old Stonehenge mystery as scientists reveal how it was actually built

New report reveals exactly which professions are most at risk from AI takeover in the next five years

12 Small Habits That Could Be Ruining Your Home

Are Brown Recluse Bites Really That Dangerous? Here’s What You Should Know

Blue Stop Signs: What Do They Mean?

16 Subtle Clues Your Partner May Not Be Loving You as You Deserve

15 Phrases You Should Never Tell a Man to Avoid Tension

MrBeast finally reveals his net worth after admitting how much is in his bank account live on stream

Influencer trapped in one of the most remote places on Earth faces brutal fine as legal fate is revealed

Texas announces major plan to fight flesh-eating flies as they prepare to descend on the US

The Volume Buttons on Your iPhone Have Countless Hidden Features

Your iPhone’s volume buttons may seem simple, but they’re packed with powerful, time-saving shortcuts. From snapping perfect photos without touching the screen to activating emergency calls in seconds, these “secret” tricks can make your iPhone ex

The reason dogs often chase and bark some people but not others

While dogs are often called “man’s best friend,” not every interaction starts with a wagging tail. Sometimes, a dog will bark, growl, or even run after a person — and the reasons go far deeper than simple playfulness.

Can You Find the Hidden Pipe? Only 2% Can!

News Post

Does Chest Pain Always Mean a Heart Attack?

10 Tasty Snacks Packed With Good-for-You Carbs

Pokeweed: The Attractive but Highly Toxic Plant Growing in Your Backyard

Goosegrass: Health Benefits and Uses

The Powerful Health Benefits of Lipton, Cloves, and Ginger Tea Every Woman Should Know

Drink this before bed to balance blood sugar & stop nighttime bathroom trips!

This vegetable oil linked to “aggressive” tumour growth, study finds

The Miracle Tree: 16 Health Benefits of Moringa & How to Use It

Clove Collagen Gel : Night Gel For A Smooth & Tight Skin

Transform your skin with fenugreek seeds

8 Natural Remedies to Cure Sinus Infections Without Antibiotics

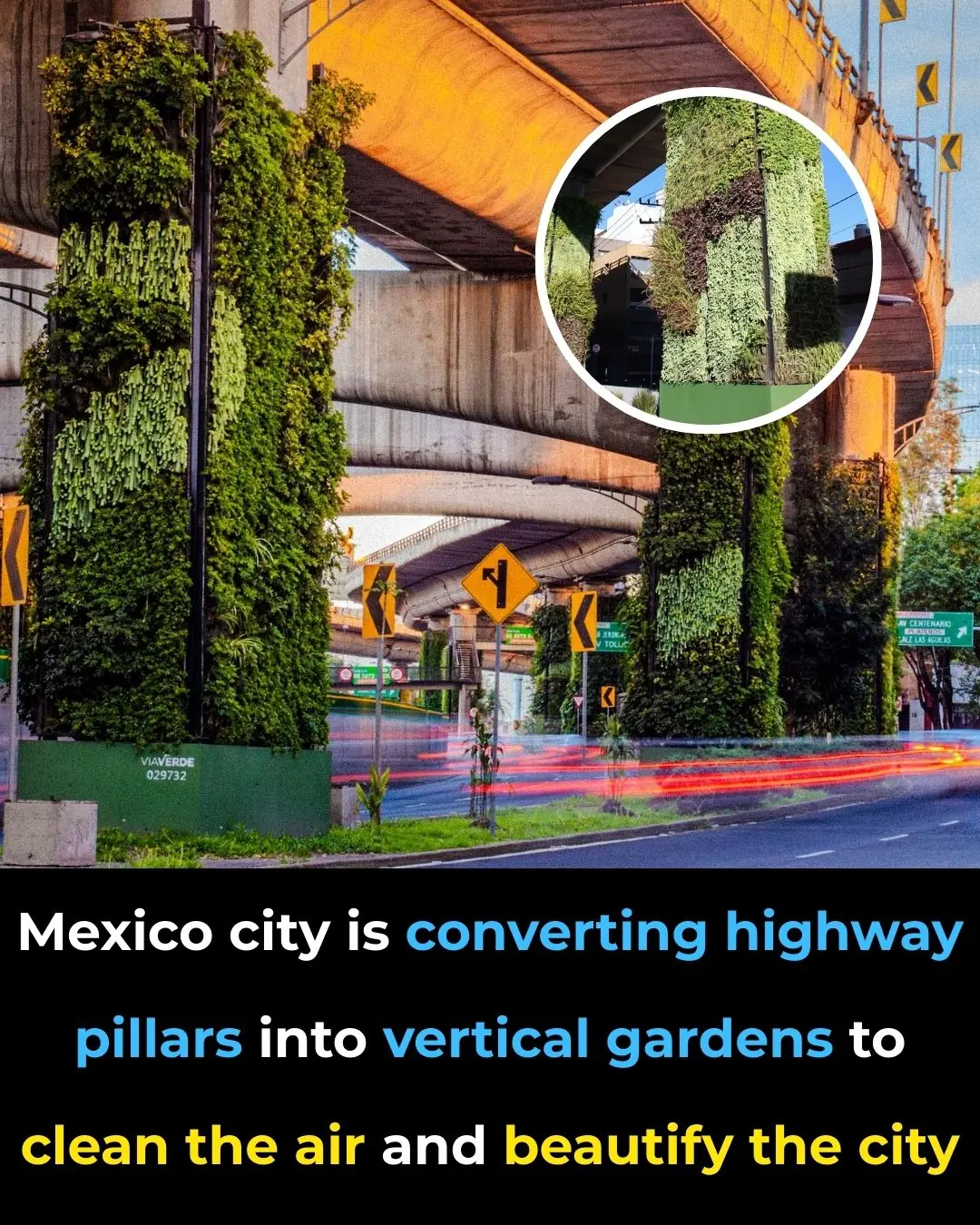

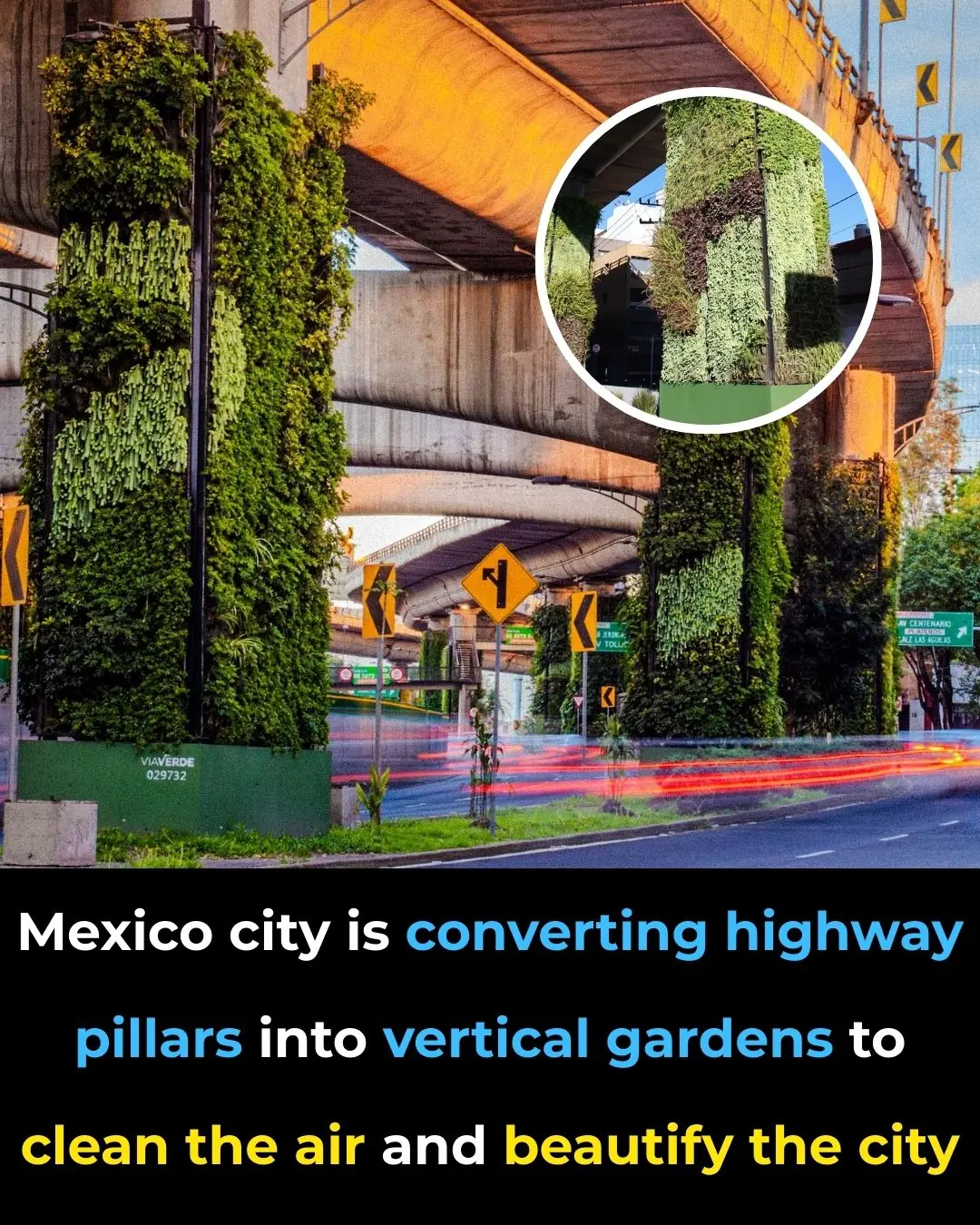

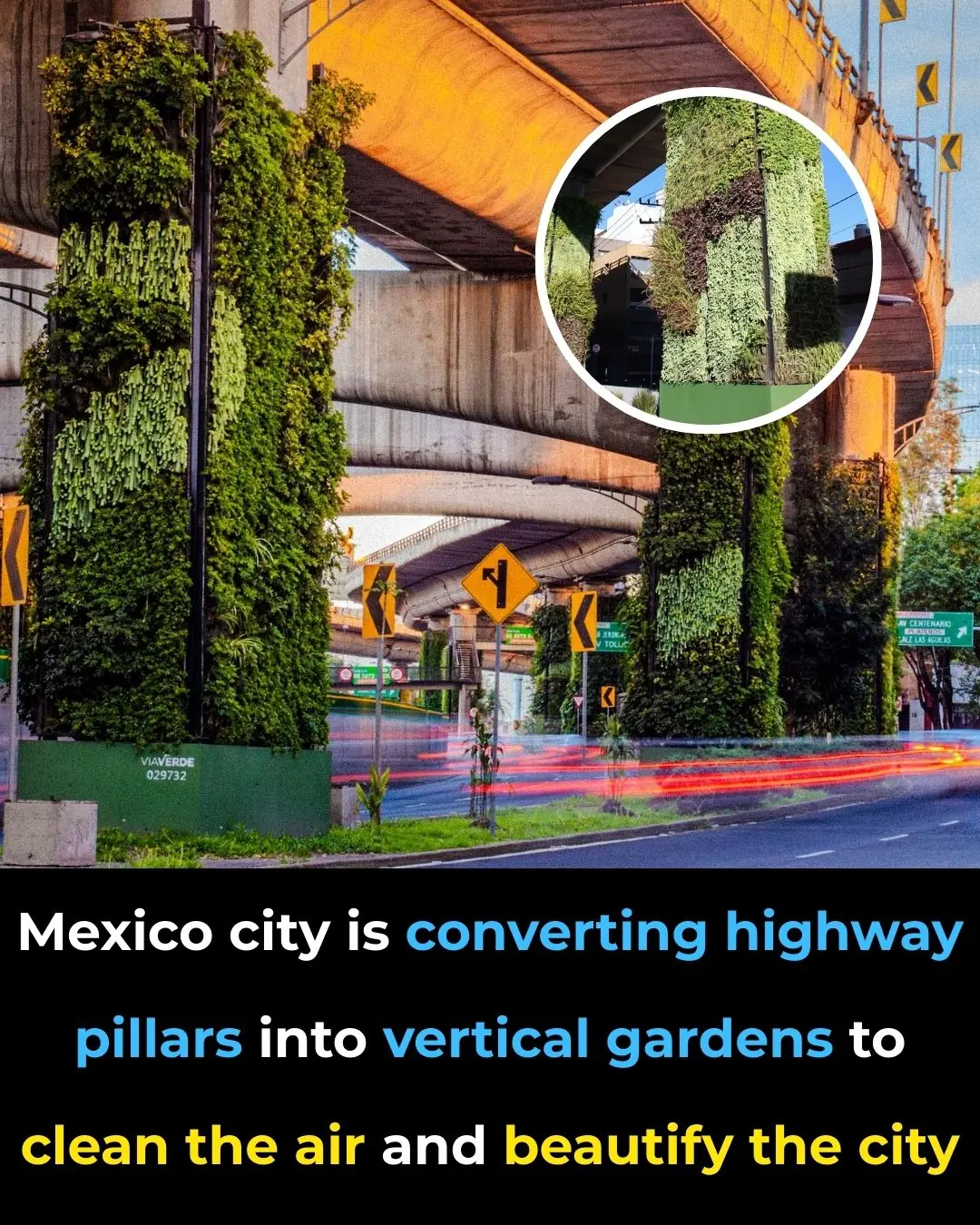

Watch – Mexico City is Converting Highway Pillars Into Vertical Gardens to Clean the Air and Beautify the City

Trump is Looking to Change Marijuana Laws in the Us and It Could Have a Major Impact

The Best Hair Growth Vitamins and Supplements to Fight Hair Loss

Foods to Eat if You Need to Poop – The Best Natural Laxatives to Relieve Constipation

The 4 vitamins this 87-year-old woman takes to stay aging (and you can too)

6 Powerful Castor Oil Benefits for Your Health and Wellness

The Possible Benefits of Himalayan Salt Lamp

The Most Effective Ways to Get Rid of Bumps on Inner Thigh (Backed by Science)