Viola Ford Fletcher, one of the last survivors of the Tulsa Race Massacre, dies at age 111

Viola Ford Fletcher, one of the last known survivors of the 1921 Tulsa Race Massacre who devoted her later years to seeking justice for the devastation of her childhood community, has died at the age of 111.

Her grandson, Ike Howard, said Monday that Fletcher passed away peacefully, surrounded by family, at a hospital in Tulsa. A woman of deep faith and remarkable resilience, she lived a life marked by hardship, perseverance, and an unwavering commitment to truth. Over the course of her long life, she raised three children, worked as a welder in a shipyard during World War II, and spent decades caring for families as a housekeeper.

Fletcher was just 7 years old when violence erupted in Tulsa’s Greenwood District on May 31, 1921. The attack began after a local newspaper published a sensationalized report accusing a Black man of assaulting a white woman. As tensions escalated outside the courthouse, armed Black residents arrived in hopes of preventing a lynching. Their presence was met with overwhelming force from white mobs. Over two days, hundreds of people were killed, thousands were left homeless, and more than 30 blocks of the prosperous Black community—often referred to as “Black Wall Street”—were burned, looted, and destroyed.

In her 2023 memoir, Don’t Let Them Bury My Story, Fletcher recalled the horrors she witnessed as a child. “I could never forget the charred remains of our once-thriving community, the smoke billowing in the air, and the terror-stricken faces of my neighbors,” she wrote. As her family fled in a horse-drawn buggy, her eyes burned from smoke and ash. She described seeing bodies piled in the streets and watching as a white man shot a Black man in the head before firing toward her own family.

For decades, Fletcher rarely spoke publicly about the massacre, later explaining that fear of retaliation and reprisals kept her silent. It was only later in life, encouraged by her grandson Howard, that she began to share her story openly. Speaking to The Associated Press in 2023, she said telling the truth about Greenwood was painful but necessary.

Howard emphasized that his grandmother believed education was essential to preventing history from repeating itself. “We don’t want history to repeat itself,” he said in a 2024 interview. “People need to understand what happened and why repair is necessary. The generational wealth that was lost—the homes, the businesses, everything—was wiped out in a single night.”

For much of the 20th century, the Tulsa Race Massacre was largely omitted from history books and public discussion. Broader acknowledgment began only in 1997, when Oklahoma formed a commission to formally investigate the violence and its long-term consequences.

In 2021, Fletcher testified before Congress, describing her childhood trauma and calling for accountability. Alongside her younger brother, Hughes Van Ellis, and fellow survivor Lessie Benningfield Randle, she joined a lawsuit seeking reparations. The Oklahoma Supreme Court dismissed the case in June 2024, ruling that the claims did not fall under the state’s public nuisance statute. Van Ellis had died the year before at age 102.

Despite legal setbacks, Fletcher remained resolute. “For as long as we remain in this lifetime, we will continue to shine a light on one of the darkest days in American history,” she and Randle said in a statement following the court’s decision.

A Justice Department review released in January 2024 under the Emmett Till Unsolved Civil Rights Crime Act detailed the scope and lasting impact of the massacre. It concluded that while federal prosecution might have been possible in the past, no legal pathway remained to pursue criminal charges a century later.

In recent years, Tulsa officials have explored ways to support descendants of massacre victims without issuing direct cash reparations. While some survivors, including Fletcher, received private donations, neither the city nor the state provided direct compensation.

Born on May 10, 1914, Fletcher spent her early childhood in Greenwood, which she described as a thriving, self-sufficient Black community during segregation. Forced to flee after the massacre, her family lived a nomadic life, working as sharecroppers and at times living in tents. She was unable to complete more than a fourth-grade education.

At 16, she returned to Tulsa and found work cleaning and designing window displays at a department store. She later married Robert Fletcher and moved to California, where she worked as a welder in a Los Angeles shipyard during World War II. After leaving an abusive marriage, she returned to Oklahoma to be closer to family, eventually settling in Bartlesville.

Throughout her life, Fletcher relied on her faith and the strength of the Black community to raise her children and endure adversity. She worked as a housekeeper well into her 80s, performing every task from cooking to childcare, and did not retire until age 85.

In her final years, Fletcher moved back to Tulsa, believing that being there would strengthen her pursuit of justice. According to Howard, the public response she received after sharing her story brought her a sense of healing.

“This whole process,” he said, “has been helpful—for her and for others who needed to hear the truth.”

News in the same category

Ja Rule 3 Losers Sucker-Punched Me Backstage If I Was Bruce Springsteen, They'd Be in Cuffs!!!

Sean Duffy urges passengers to dress better, be more polite while flying during ‘busiest Thanksgiving’ ever

Examination of the Hip-Hop Mogul

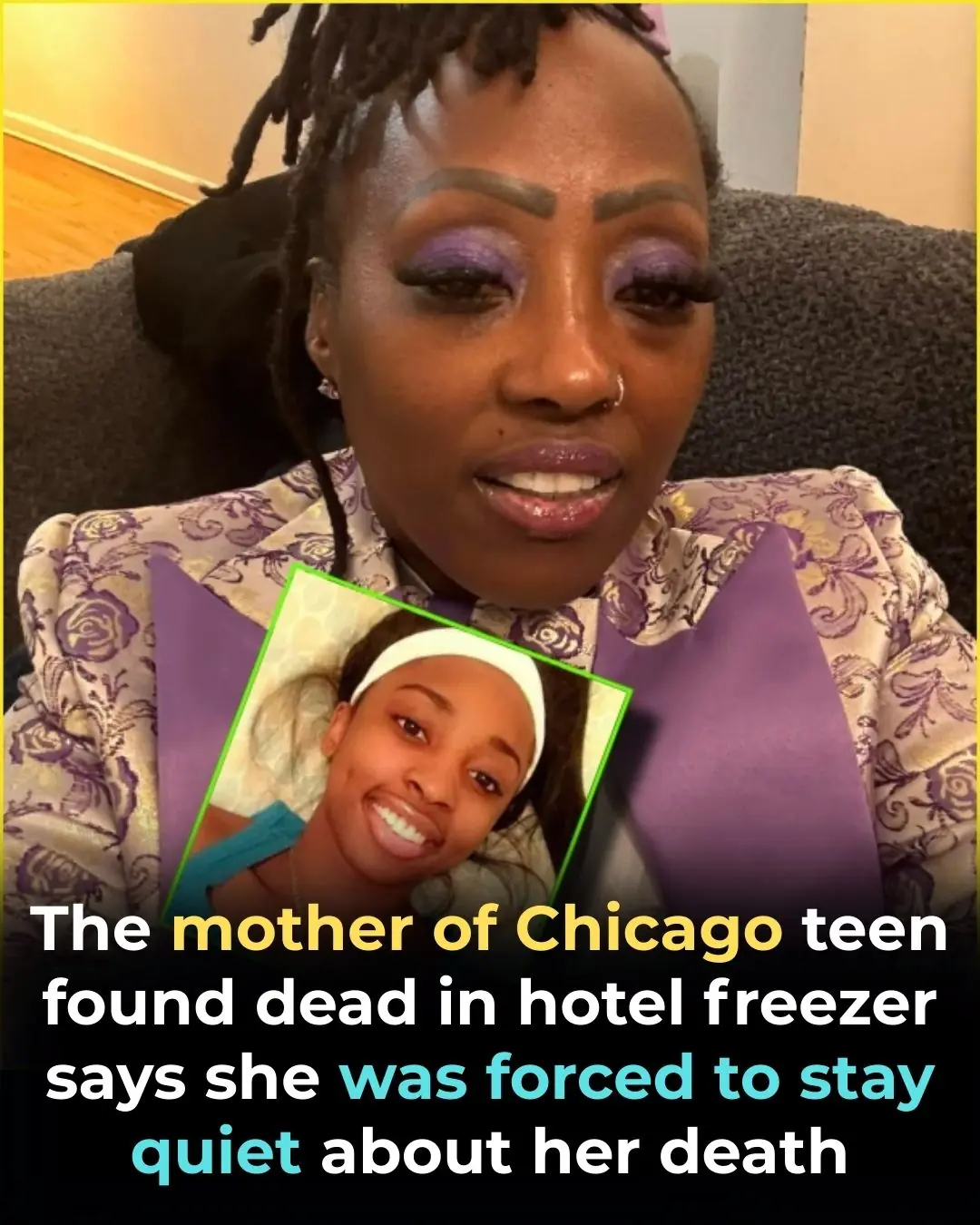

‘I’ve Stayed Quiet Long Enough’: Kenneka Jenkins’ Mother Makes Explosive Claims About Her Mysterious Death and the $10 Million Settlement

A mistaken text connected them. Now they’ve become one of America’s favorite Thanksgiving traditions

‘RHOA’ Alum Kandi Burruss’ Ex Todd Tucker Demands Primary Custody, Questions Prenupital Agreement (Exclusive)

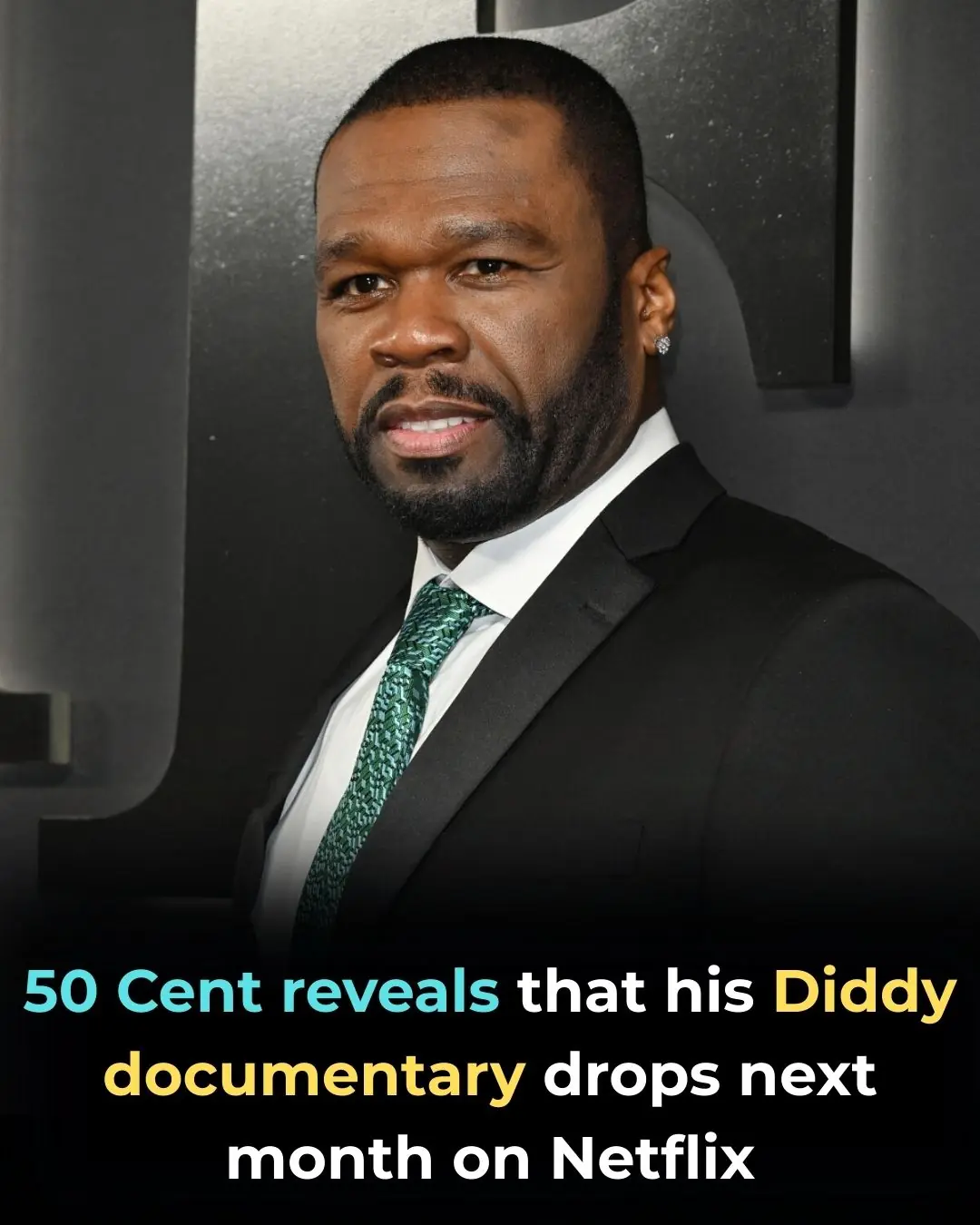

Curtis '50 Cent' Jackson on why he executive-produced new Sean 'Diddy' Combs doc

The Game Calls for Diddy and R. Kelly’s Release at His Birthday Party: ‘Free All the Freaky Homies’

Jada Pinkett Smith Hit With $3 Million Lawsuit For Allegedly Threatening Will’s Friend

Venus Williams celebrates engagement to Andrea Preti with tropical photo shoot

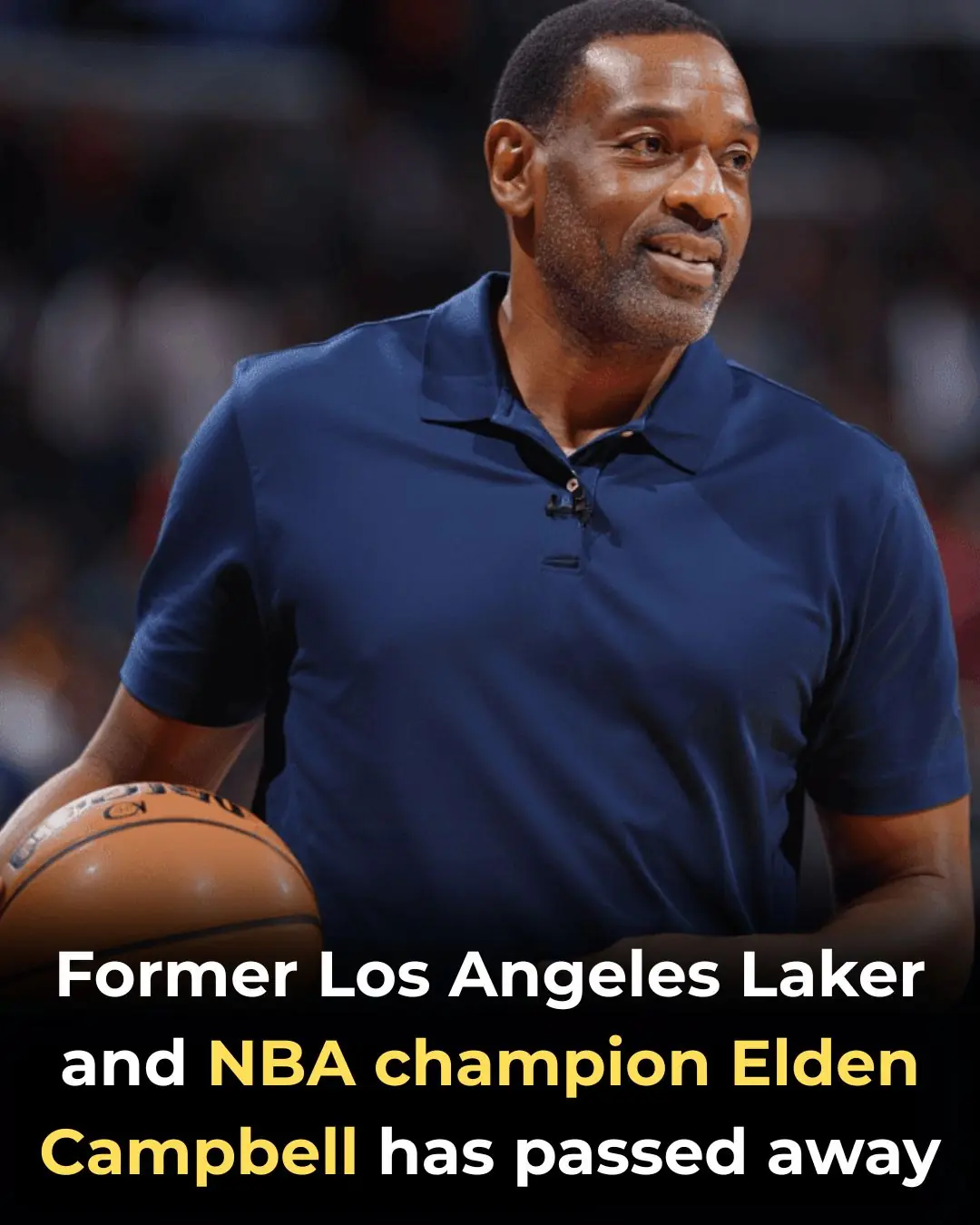

Elden Campbell, former Lakers first-round pick who won championship with Pistons, dies at 57

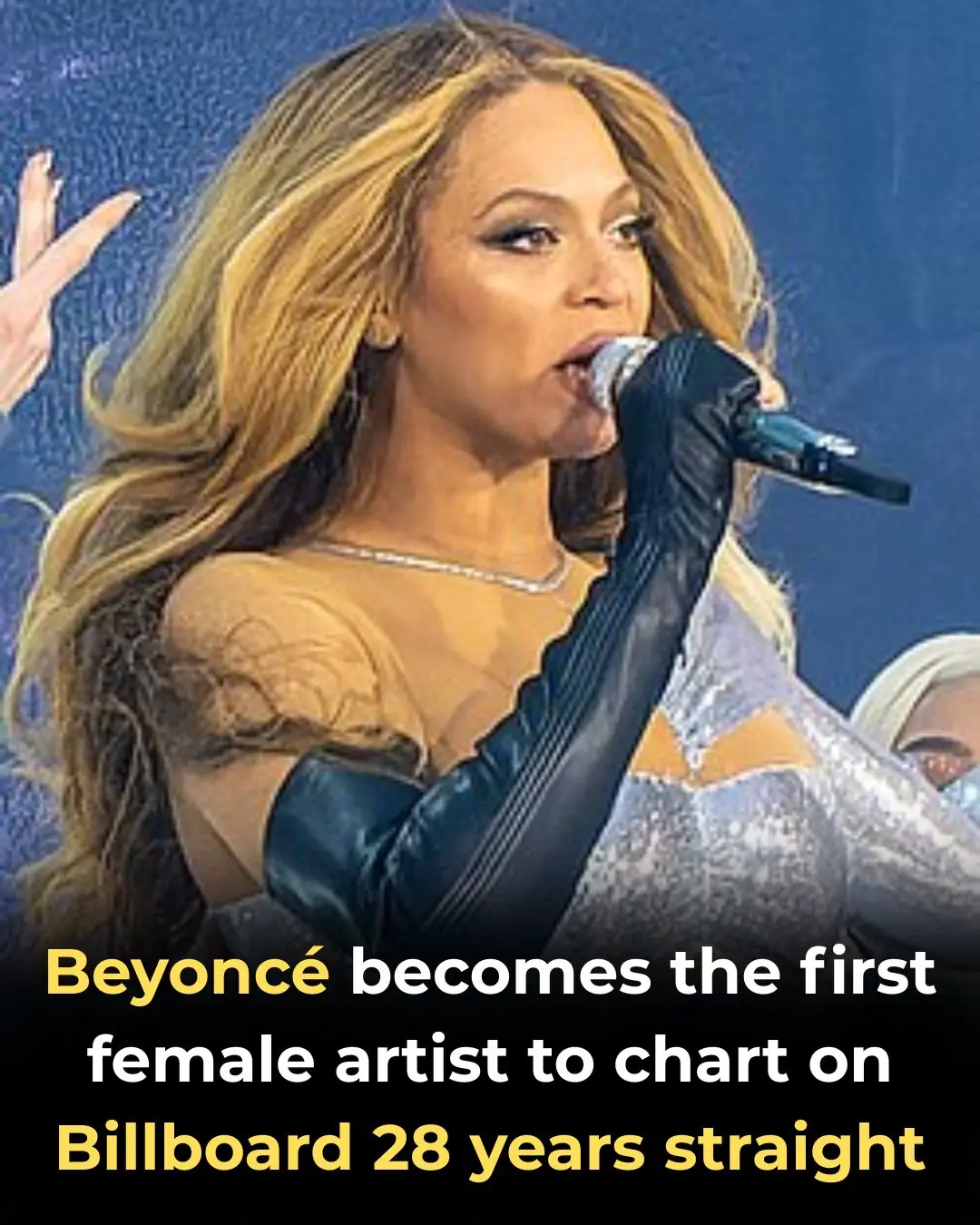

Beyoncé Makes Billboard Hot 100 History by Charting for This Many Consecutive Years

Tracy Morgan donates over $200K to feed 19K families, talks health and career

Netflix hits back at claims that Diddy documentary footage was stolen

Netflix hits back at claims that Diddy documentary footage was stolen

Philly's Quinta Brunson launches field trip fund for 117,000 students

The 23XI/Front Row vs. Nascar Lawsuit Shows Michael Jordan Still ‘Takes it Personally.’ Here’s Why Sometimes You Should Too

Flex Alexander Reflects on Role as Michael Jackson in 2004 Biopic, Says Singer Hated the Film

News Post

Everyone Fears Diabetes, but Diabetes “Fears” These 5 Foods

A Hard-Earned Lesson for Middle-Aged Parents: Let Go of These Habits, and Your Children Will Naturally Grow Closer

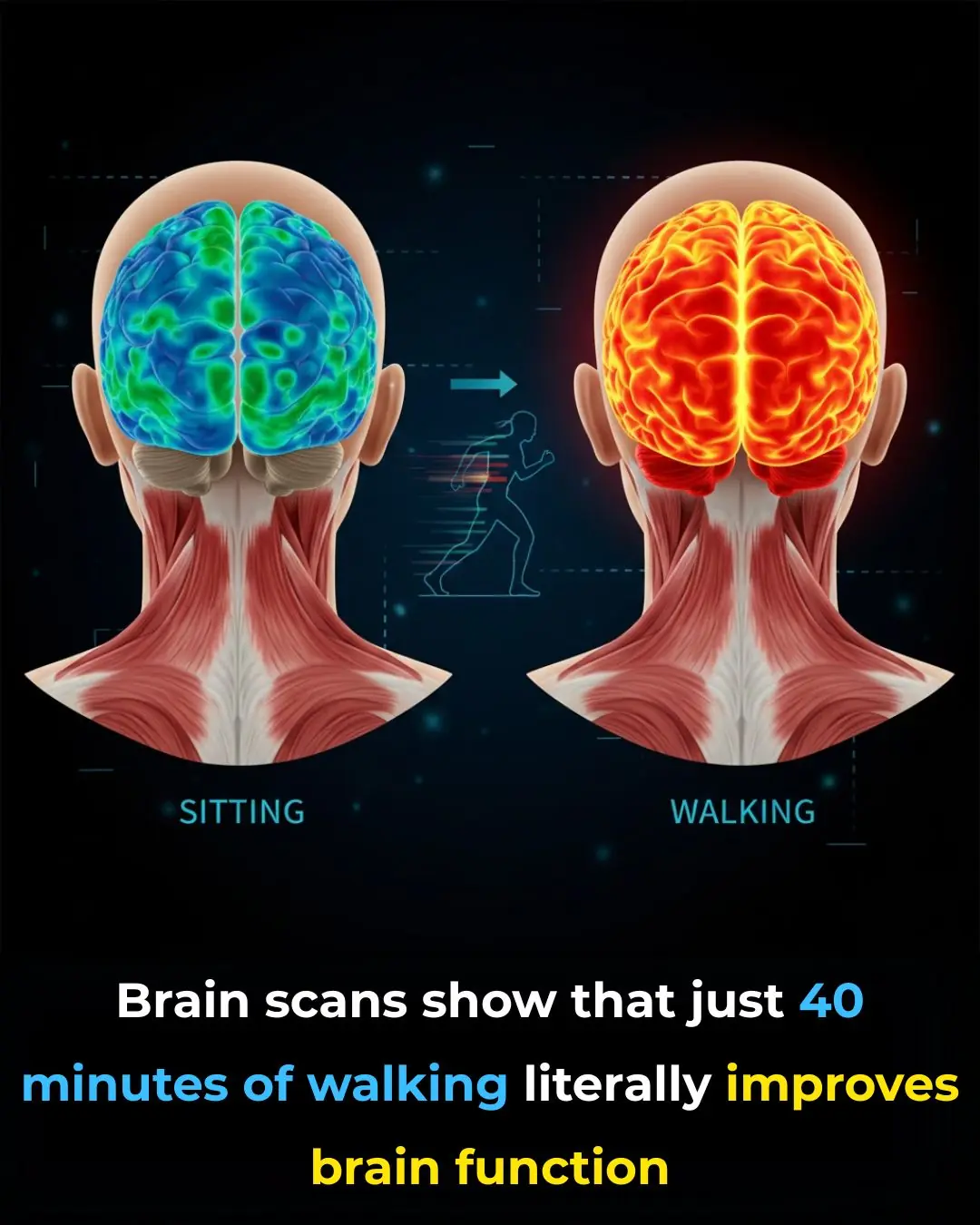

How Walking Activates the Brain: The Hidden Link Between Movement, Focus, and Mental Clarity

It’s Time to Protect Your Stomach: Remove These 5 Popular Vietnamese Breakfast Foods from Your Morning Menu

Should You Choose Dark-Colored or Light-Colored Pork?

Tips for growing ginger at home for big, plump tubers that you can enjoy all year round.

Putting these four things in the rice container will not only protect the rice from pests, but also make it taste better.

The secret to cooking fish without a fishy smell: 4 simple spices everyone should try.

Pour this type of water into the electric kettle, and all the limescale will be gone, leaving it sparkling clean like new.

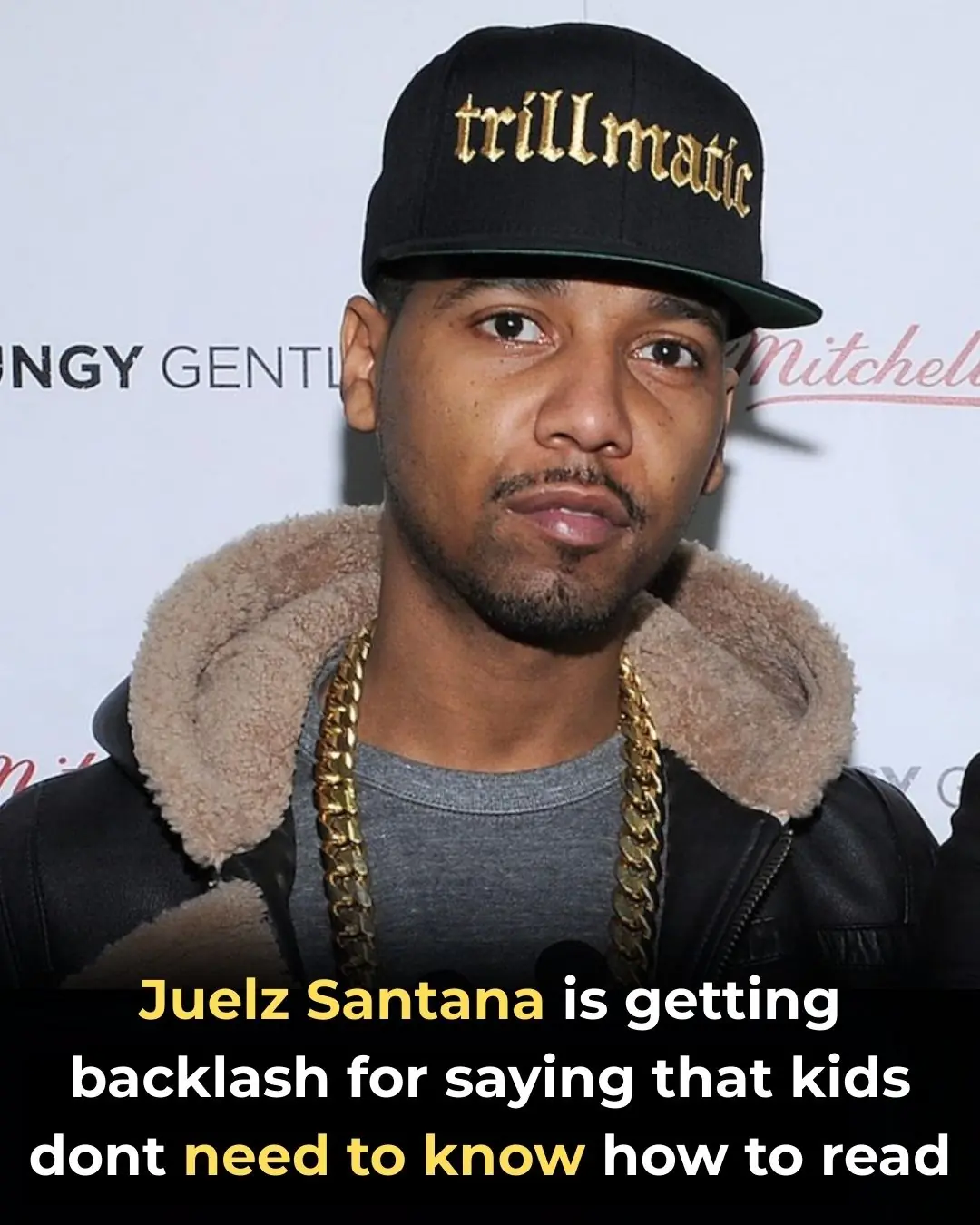

Juelz Santana Dragged Online After Saying Kids “Don’t Really Need to Know How to Read”

Ja Rule 3 Losers Sucker-Punched Me Backstage If I Was Bruce Springsteen, They'd Be in Cuffs!!!

Sean Duffy urges passengers to dress better, be more polite while flying during ‘busiest Thanksgiving’ ever

Examination of the Hip-Hop Mogul

‘I’ve Stayed Quiet Long Enough’: Kenneka Jenkins’ Mother Makes Explosive Claims About Her Mysterious Death and the $10 Million Settlement

Tips for growing ginger at home for big, plump roots that can be eaten all year round

How to store chili peppers for several months so they stay as fresh as when picked, with plump flesh that doesn’t dry out and retains its flavor

A Clever Alternative to Caramel Coloring: Using Cola to Braise Meat Perfectly

How to Improve Blood Circulation Naturally (Research Based)