Health 28/12/2025 21:19

Hidden Spread of Pseudomonas aeruginosa From Lung to Gut in Hospitalized Patients

News in the same category

Health 28/12/2025 23:34

Thymoquinone and Breast Cancer Cell Suppression: Evidence from Preclinical Research

Health 28/12/2025 23:33

Ginger Supplementation and Cardiovascular Inflammation: Evidence from a Double-Blind Randomized Clinical Trial

Health 28/12/2025 23:31

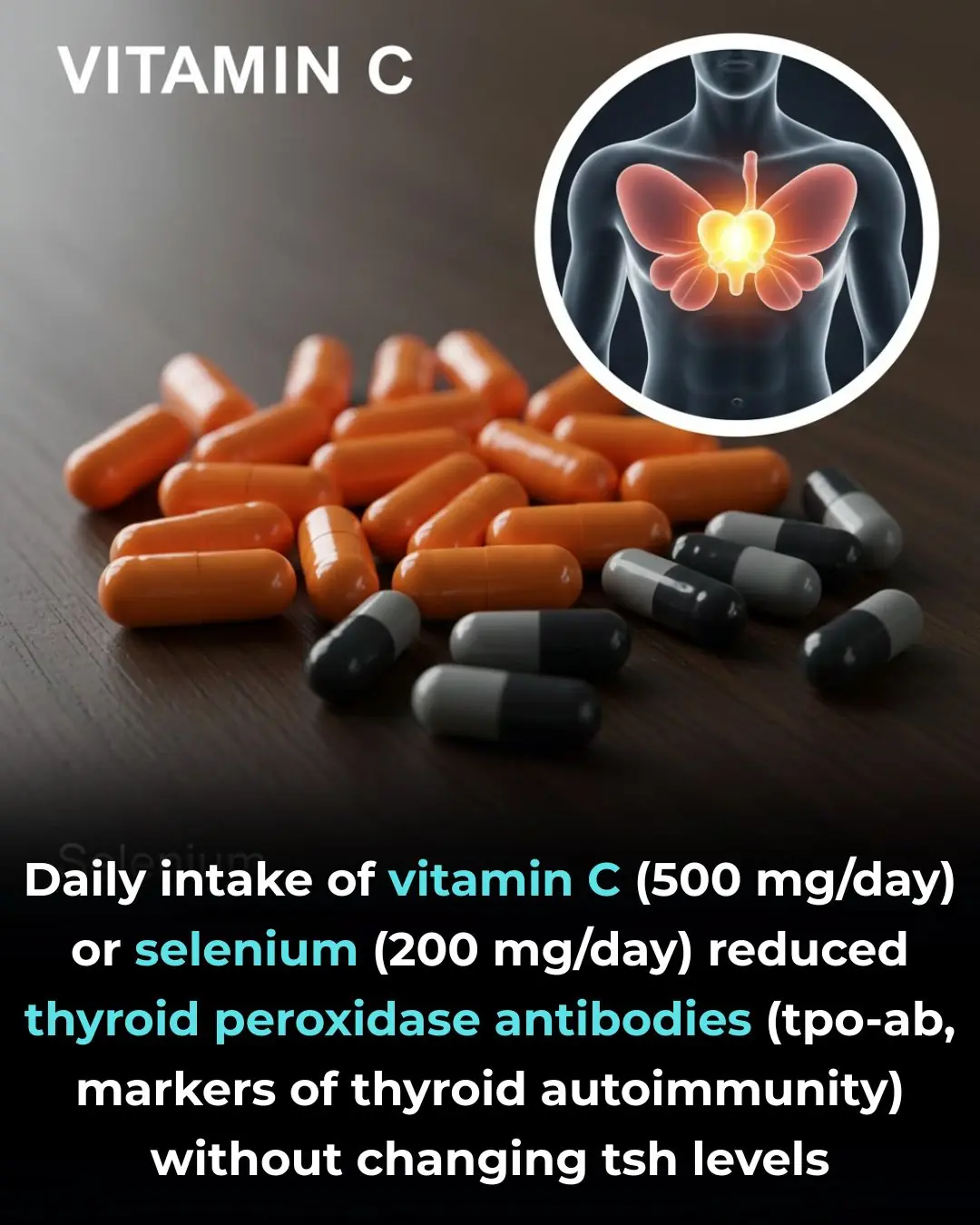

Antioxidant Supplementation and Thyroid Autoimmunity: Evidence from a Randomized Controlled Trial

Health 28/12/2025 23:30

Chios Mastic Gum as an Anti-Inflammatory Intervention in Crohn’s Disease and Vascular Inflammation

Health 28/12/2025 23:29

Garlic Supplementation and Metabolic Improvement in Non-Alcoholic Fatty Liver Disease

Health 28/12/2025 23:28

Potassium Deficiency – Causes, Symptoms and What To Do

Health 28/12/2025 22:53

14 Warning Signs of Low Magnesium Levels and What to Do About It (Science Based)

Health 28/12/2025 22:51

Proven Health Benefits of Beets and Fermented Beets (Science Based)

Health 28/12/2025 22:47

3 Reasons Onions Might Upset Your Stomach

Health 28/12/2025 22:23

MRI vs PET: Which Imaging Modality Better Detects Prostate Cancer Recurrence?

Health 28/12/2025 21:22

‘Tis the Season to Help People Avoid Holiday Heart Syndrome

Health 28/12/2025 21:12

Got a lump on your neck, back or behind your ear? This is what you need to know

Health 28/12/2025 21:03

What Your Skin Could Be Telling You About Hidden Health Issues

Health 28/12/2025 21:01

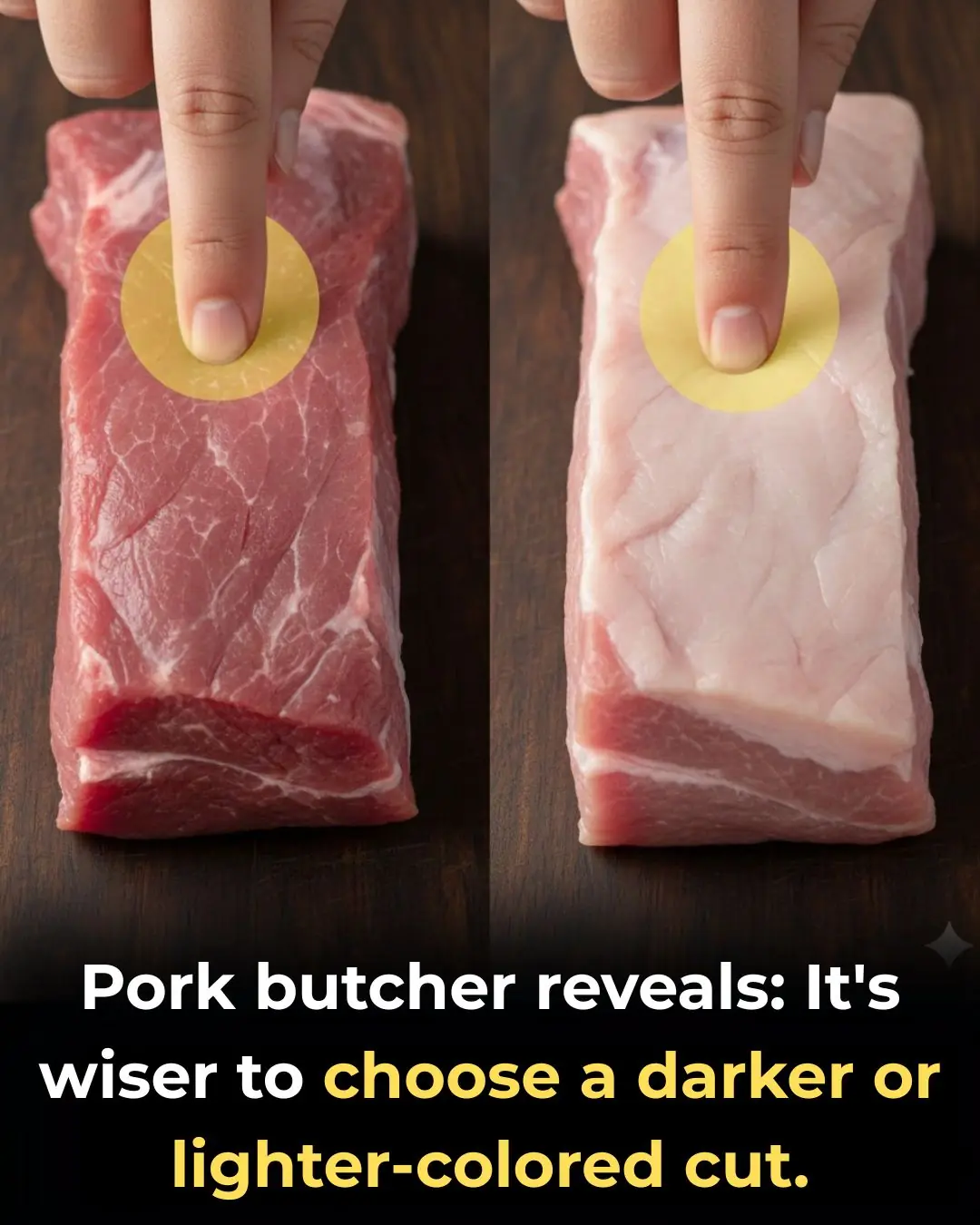

How to Choose Fresh and Delicious Pork: Should You Pick Lighter or Darker Pieces?

How to Choose Fresh and Delicious Pork: Should You Pick Lighter or Darker Pieces?

Health 28/12/2025 15:17

4 Types of Vegetables Most Effective in Preventing Cancer, According to Doctors: Eating Them Regularly Is Great for Your Health

Health 28/12/2025 10:30

Stroke and Cerebral Infarction Prevention: Remember These 3 Indicators, 1 Disease, and 6 Key Habits

Health 28/12/2025 10:26

Optimism as a Psychosocial Predictor of Exceptional Longevity

Health 27/12/2025 22:44

Why Ages 36–46 Matter: Midlife as a Critical Window for Long-Term Health

Health 27/12/2025 22:41

News Post

Bee Propolis and Infertility in Endometriosis: Evidence from a Pilot Randomized Clinical Trial

Health 28/12/2025 23:34

Thymoquinone and Breast Cancer Cell Suppression: Evidence from Preclinical Research

Health 28/12/2025 23:33

Ginger Supplementation and Cardiovascular Inflammation: Evidence from a Double-Blind Randomized Clinical Trial

Health 28/12/2025 23:31

Antioxidant Supplementation and Thyroid Autoimmunity: Evidence from a Randomized Controlled Trial

Health 28/12/2025 23:30

Chios Mastic Gum as an Anti-Inflammatory Intervention in Crohn’s Disease and Vascular Inflammation

Health 28/12/2025 23:29

Garlic Supplementation and Metabolic Improvement in Non-Alcoholic Fatty Liver Disease

Health 28/12/2025 23:28

If you drink cucumber water every morning, this is what happens to your body

Tips 28/12/2025 22:59

I soaked my feet in apple cider vinegar. 15 mins later, this is what happened

Tips 28/12/2025 22:57

I need this ‘Liquid Gold.’

Tips 28/12/2025 22:55

Potassium Deficiency – Causes, Symptoms and What To Do

Health 28/12/2025 22:53

14 Warning Signs of Low Magnesium Levels and What to Do About It (Science Based)

Health 28/12/2025 22:51

Proven Health Benefits of Beets and Fermented Beets (Science Based)

Health 28/12/2025 22:47

Putting this in the vase box not only helps protect the chrysanthemums but also makes the vase more delicious

Tips 28/12/2025 22:41

How to preserve cilantro so it stays fresh, green, and fragrant for a whole month

Tips 28/12/2025 22:33

3 Reasons Onions Might Upset Your Stomach

Health 28/12/2025 22:23

Vaseline Uses and Benefits for Skin, Lips and Hair | Petroleum Jelly Benefits

Beatuty Tips 28/12/2025 22:21

Beetroot Face Gel for Clear Skin – Rosy Cheeks & Pink Blushing Skin

Beatuty Tips 28/12/2025 22:16

How i use CUCUMBER for Skin & Eyes : Remove Dark Circles & Get Glowing Skin

Beatuty Tips 28/12/2025 22:13

Tips for removing grease from an air fryer

Tips 28/12/2025 21:49

There’s a warm spot on my hardwood floor even though the heat isn’t running under there, and no technician can come soon. What could cause that?

Tips 28/12/2025 21:34