Facts 15/12/2025 16:42

Why Hawaii Is Releasing One Million Mosquitoes a Week to Save Endangered Birds

News in the same category

Facts 15/12/2025 22:21

Overview Energy's Bold Plan to Beam Power from Space to Earth Using Infrared Lasers

Facts 15/12/2025 22:19

Japan’s Ghost Homes Crisis: 9 Million Vacant Houses Amid a Shrinking Population

Facts 15/12/2025 22:17

Japan’s Traditional Tree-Saving Method: The Beautiful and Thoughtful Practice of Nemawashi

Facts 15/12/2025 22:15

Swedish Billionaire Buys Logging Company to Save Amazon Rainforest

Facts 15/12/2025 22:13

The Farmer Who Cut Off His Own Finger After a Snake Bite: A Tale of Panic and Misinformation

Facts 15/12/2025 22:11

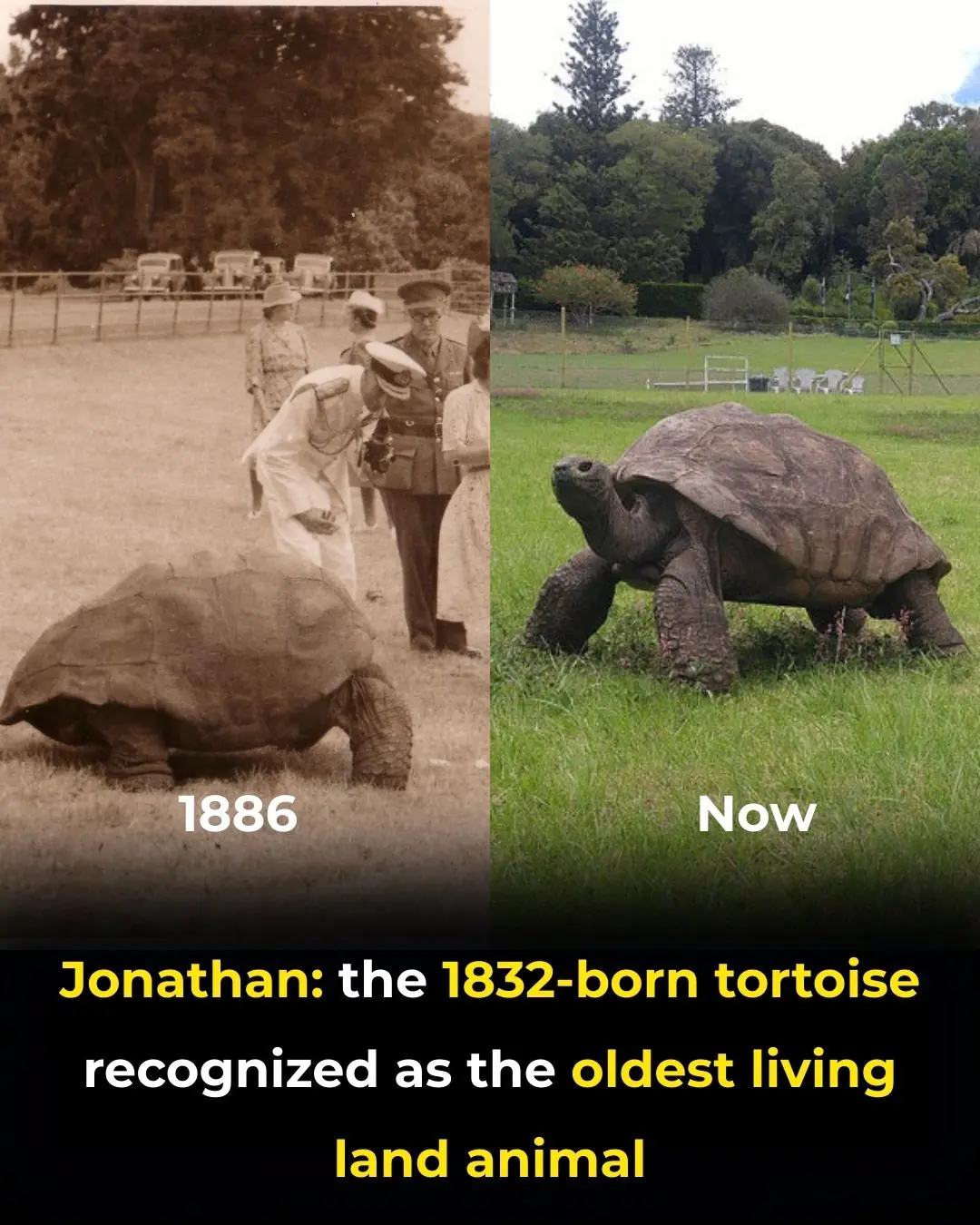

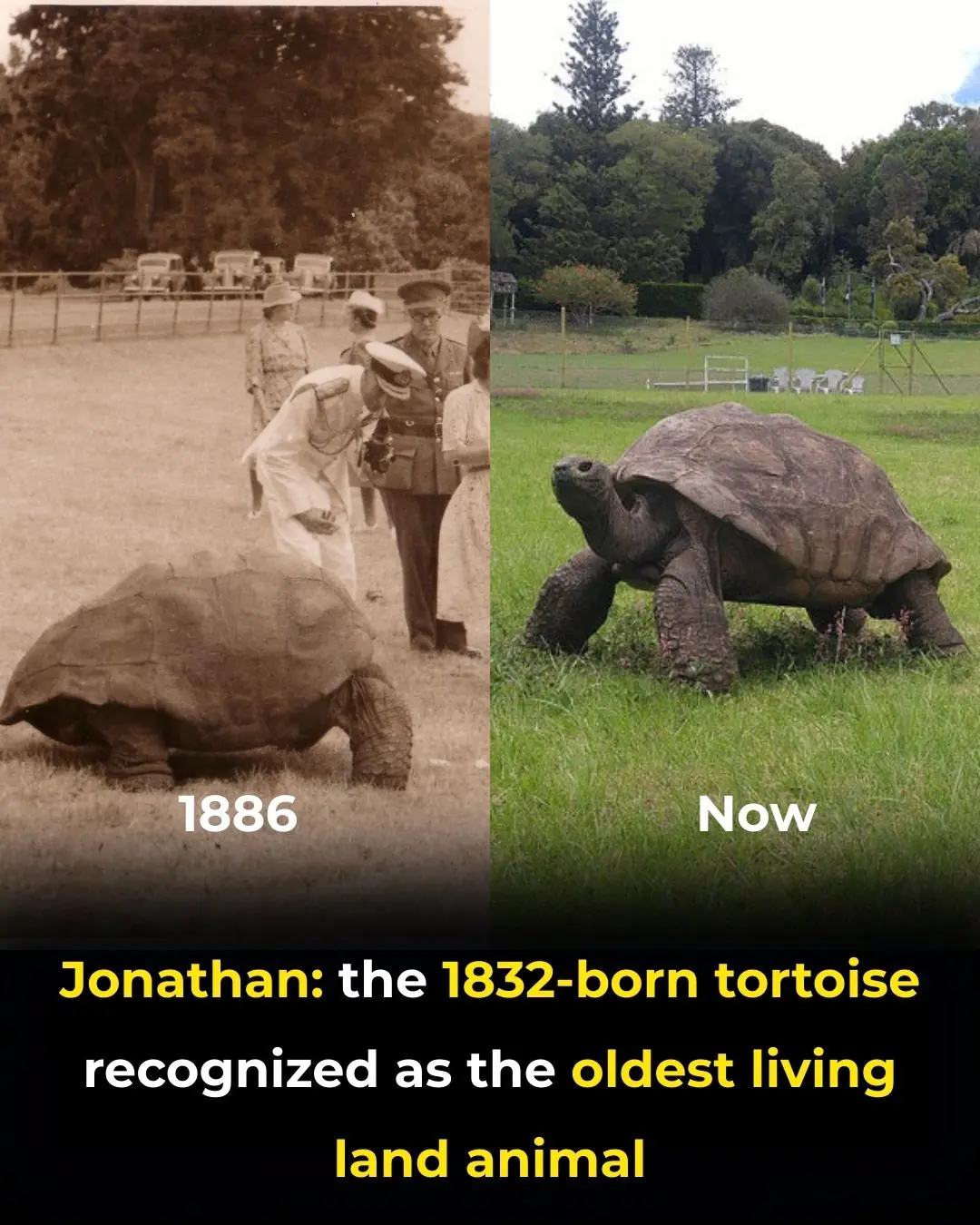

Meet Jonathan: The 193-Year-Old Tortoise Who Has Witnessed Three Centuries

Facts 15/12/2025 22:09

Hawaii’s Million Mosquitoes a Week: A Bold Move to Save Endangered Birds

Facts 15/12/2025 22:07

Scientists Achieve Historic Breakthrough by Removing HIV DNA from Human Cells, Paving the Way for a Potential Cure

Facts 15/12/2025 21:57

Belgium’s “Pay What You Can” Markets: Redefining Access to Fresh Food with Community and Solidarity

Facts 15/12/2025 21:48

China's Betavolt Unveils Coin-Sized Nuclear Battery with a Potential 100-Year Lifespan

Facts 15/12/2025 21:47

Japan’s Morning Coffee Kiosks: A Quiet Ritual for a Peaceful Start to the Day

Facts 15/12/2025 21:43

13-Year-Old Boy From Nevada Buys His Single Mother a Car Through Hard Work and Dedication

Facts 15/12/2025 21:39

ReTuna: The World’s First Shopping Mall Built on Repair, Reuse, and the Circular Economy

Facts 15/12/2025 21:38

Revolutionary Cancer Treatment Technique: Restoring Cancer Cells to Healthy States

Facts 15/12/2025 21:18

The Critical Role of Sleep in Brain Health: How Sleep Deprivation Impairs Mental Clarity and Cognitive Function

Facts 15/12/2025 21:14

Scientists Discover The Maximum Age a Human Can Live To

Facts 15/12/2025 21:11

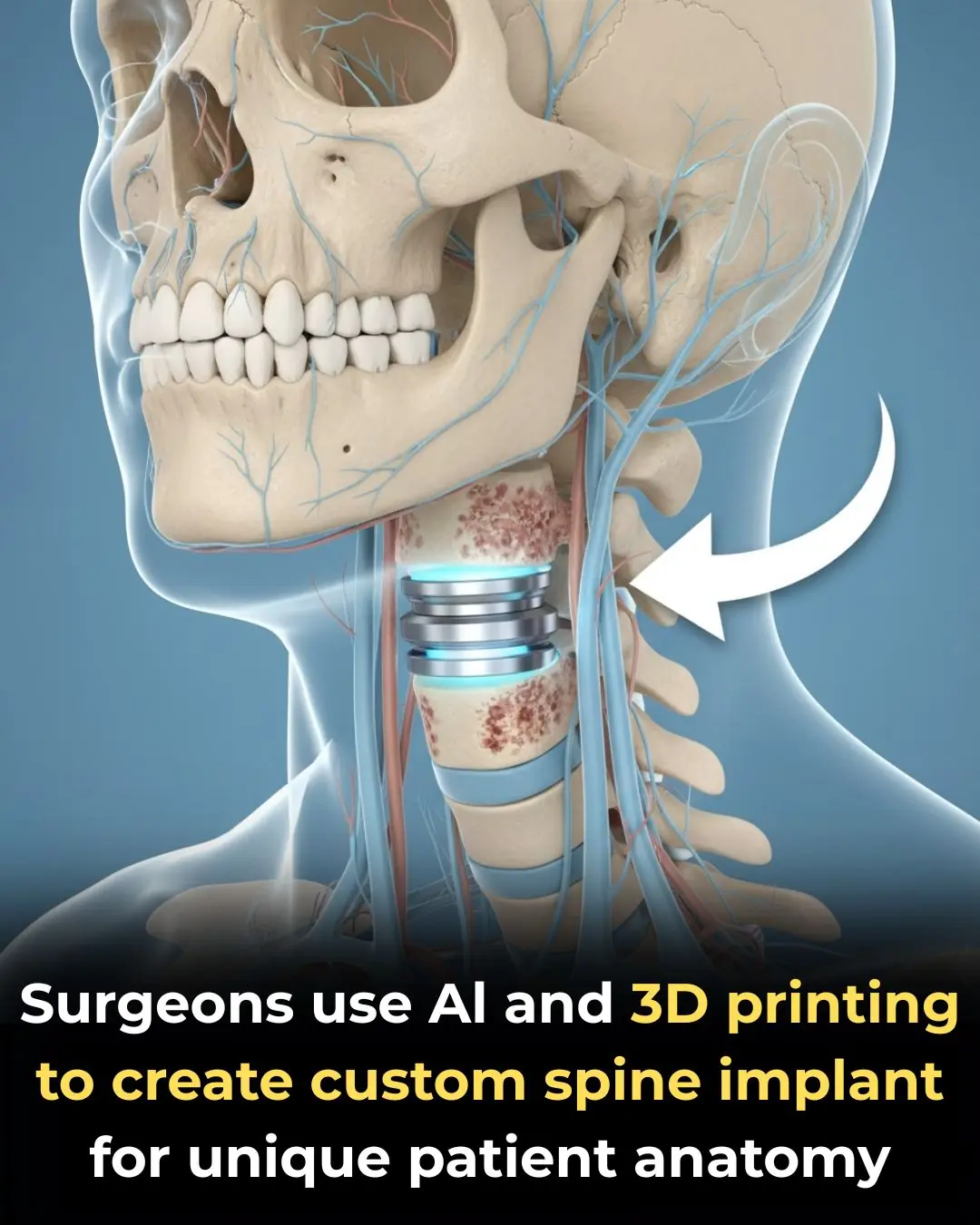

UC San Diego Health Performs World’s First Personalized Anterior Cervical Spine Surgery Using AI and 3D Printing

Facts 15/12/2025 21:11

Could Your Blood Type Be Influencing How You Age

Facts 15/12/2025 21:09

Promising Early Results for ELI-002 2P: A New Vaccine Targeting Pancreatic Cancer

News Post

Tiny Pumpkin Toadlet Discovered in Brazil's Atlantic Forest: A New Species of Vibrantly Colored Frog

Facts 15/12/2025 22:21

Overview Energy's Bold Plan to Beam Power from Space to Earth Using Infrared Lasers

Facts 15/12/2025 22:19

Japan’s Ghost Homes Crisis: 9 Million Vacant Houses Amid a Shrinking Population

Facts 15/12/2025 22:17

Japan’s Traditional Tree-Saving Method: The Beautiful and Thoughtful Practice of Nemawashi

Facts 15/12/2025 22:15

Swedish Billionaire Buys Logging Company to Save Amazon Rainforest

Facts 15/12/2025 22:13

The Farmer Who Cut Off His Own Finger After a Snake Bite: A Tale of Panic and Misinformation

Facts 15/12/2025 22:11

Meet Jonathan: The 193-Year-Old Tortoise Who Has Witnessed Three Centuries

Facts 15/12/2025 22:09

Hawaii’s Million Mosquitoes a Week: A Bold Move to Save Endangered Birds

Facts 15/12/2025 22:07

Scientists Achieve Historic Breakthrough by Removing HIV DNA from Human Cells, Paving the Way for a Potential Cure

Facts 15/12/2025 21:57

Belgium’s “Pay What You Can” Markets: Redefining Access to Fresh Food with Community and Solidarity

Facts 15/12/2025 21:48

China's Betavolt Unveils Coin-Sized Nuclear Battery with a Potential 100-Year Lifespan

Facts 15/12/2025 21:47

Japan’s Morning Coffee Kiosks: A Quiet Ritual for a Peaceful Start to the Day

Facts 15/12/2025 21:43

13-Year-Old Boy From Nevada Buys His Single Mother a Car Through Hard Work and Dedication

Facts 15/12/2025 21:39

ReTuna: The World’s First Shopping Mall Built on Repair, Reuse, and the Circular Economy

Facts 15/12/2025 21:38

Liver Damage Linked to Supplement Use Is Surging, Sparking Scientific Alarm

Health 15/12/2025 21:37

No More Fillings? Scientists Successfully Grow Human Teeth in the Lab

Health 15/12/2025 21:34

Lab Study Shows Dandelion Root Kills Over 90% of Colon Cancer Cells In Just Two Days

Health 15/12/2025 21:30

7 Red Flag Phrases Narcissists Use to Exert Control During Arguments

Health 15/12/2025 21:25

Although they're both peanuts, red-shelled and white-shelled peanuts have significant differences. Read this so you don't buy them indiscriminately again!

Tips 15/12/2025 21:23

If These 8 Activities Energize You Instead of Drain You, You’re Likely a Highly Intelligent Introvert

Health 15/12/2025 21:22