56 Percent Of Americans Don’t Think We Should Teach Arabic Numerals In School

Something troubling — and surprisingly revealing — happened when 3,624 Americans answered what looked like an innocent question about school curriculum. More than half rejected the idea of teaching a fundamental mathematical system in U.S. classrooms. CivicScience, the market research firm that ran the poll, expected a routine opinion check. What they got instead exposed something far deeper about how people think when instinct, fear, and tribal identity take over rational judgment.

Confusing Results From a Simple Question

The survey found that 56% of respondents opposed teaching Arabic numerals in American schools. Twenty-nine percent supported the idea, and 15% had no opinion. At first glance, these numbers might look like any typical educational debate — people disagree all the time about what belongs in textbooks.

Except this time, something was very different.

You’ve Used Arabic Numerals Every Day of Your Life

Arabic numerals are the digits 0 through 9, the symbols you use for everything:

checking the time, reading price tags, typing on a keyboard, navigating streets, baking, budgeting, calculating taxes, and scrolling your phone. If you're reading this sentence, you're using them.

The system is universal. It’s used in the U.S., Europe, Australia, and nearly every country on the planet. Even places with their own historic number systems — such as China or Japan — use Arabic numerals in science, finance, and daily life.

Despite this, 2,020 Americans essentially voted against teaching the very system that makes modern mathematics possible. CivicScience CEO John Dick later described the result as “the saddest and funniest testament to American bigotry we’ve ever seen in our data.”

How the Survey Set the Trap

CivicScience intentionally asked the question without defining the term Arabic numerals. No hint. No explanation. The phrasing forced respondents to rely on whatever associations the phrase triggered.

“Our goal… was to tease out prejudice among those who didn’t understand the question,” Dick wrote on Twitter.

And it worked. Instead of admitting confusion or choosing “no opinion,” many people answered based on emotion. Pollsters have long known that when people encounter unfamiliar terms, they often stop analyzing and start reacting — especially when a word sounds foreign, political, or connected to a cultural group they distrust.

Politics Meets Mathematics

Unsurprisingly, political identity shaped responses:

-

72% of Republicans opposed teaching Arabic numerals.

-

40% of Democrats did the same.

Educational background between the two groups showed no significant difference, suggesting the divide wasn’t about knowledge — it was about the word Arabic. For some Republican respondents, the association with the Middle East or Islam triggered a reflexive rejection. Democrats, while less reactive, still revealed a significant lack of understanding.

In both groups, ideology overshadowed basic information. Americans couldn’t recognize the digits they use every hour of their lives simply because the proper name sounded foreign.

Democrats Fell Into Their Own Trap

CivicScience didn’t stop at one question. Another asked whether schools should teach “the creation theory of Catholic priest Georges Lemaître.”

-

73% of Democrats opposed including it in science classes.

-

Only 33% of Republicans did.

The phrase “Catholic priest” paired with “creation theory” triggered progressive resistance. Many assumed it referred to a religious doctrine that contradicts evolutionary science.

But Georges Lemaître wasn’t arguing theology. He was a trained physicist and cosmologist who proposed the idea that the universe began from a single expanding point — the theory we now call the Big Bang.

In other words, many Democrats voted against teaching one of the most important scientific breakthroughs of the 20th century for the same reason Republicans rejected Arabic numerals: the label sounded like something they didn’t trust.

The Real Origin of Arabic Numerals

Despite their name, Arabic numerals did not originate in Arabia.

-

Indian mathematicians developed them in the 6th or 7th century.

-

Middle Eastern scholars later adopted, improved, and spread the system.

-

European scholars learned it through Arabic writings, so they named it “Arabic numerals.”

The system replaced Roman numerals and helped make algebra, physics, engineering, and modern computation possible. Without these ten digits, everything from banking to space exploration would collapse.

And yet, the majority of respondents wanted these numbers removed from school curricula.

This Isn’t the First Time Americans Did This

CivicScience’s findings echo a notorious 2015 poll by Public Policy Polling. Respondents were asked whether the U.S. should bomb Agrabah.

-

41% of Trump supporters said yes.

-

19% of Democrats agreed.

Agrabah is not a real place — it’s the fictional kingdom from Disney’s Aladdin. Poll participants reacted not to facts but to how the name sounded.

The pattern is the same: when confronted with unfamiliar, Middle Eastern-sounding words, many Americans defaulted to distrust or aggression rather than curiosity.

Social Media Reacted With Shock — and Humor

When John Dick posted the Arabic numerals results, Twitter exploded. Some users made jokes about returning to “Judeo–Christian mathematics” by switching to Roman numerals. Others rewrote poll results entirely in ancient symbols for comedic effect.

But beneath the humor lay serious concerns:

How could so many people not recognize the numerical system they rely on every day? What does this say about the way Americans process information? And what does it reveal about the power of language to trigger bias?

What the Survey Reveals About Human Thinking

The poll highlights a pattern that extends far beyond education:

-

People often prefer certainty over accuracy.

-

Many would rather choose a side than admit “I don’t know.”

-

Keywords can override logic, especially when tied to political or cultural tribalism.

-

Prejudice fills the gaps where knowledge is missing.

Dick emphasized that both political tribes displayed bias. Republicans reacted to the word “Arabic.” Democrats reacted to the word “Catholic.” Neither group paused to consider the actual content of the question.

This isn’t just about numbers or scientific theories — it’s about how people form beliefs in an age where identity and ideology often matter more than facts.

A Reminder of How Easily We Misjudge What We Don’t Understand

Arabic numerals are a cornerstone of modern civilization. Without them, you couldn’t use your phone, read your bills, follow a recipe, or even understand the date. Yet most Americans in the survey wanted them removed from classrooms simply because the name sounded foreign.

This poll is a reminder of how quickly people can misinterpret information — not because they lack intelligence, but because they rely on instinct before curiosity.

The ten digits we use every day aren’t just mathematical symbols. They’re a testament to global knowledge, cultural exchange, and centuries of intellectual progress. And perhaps the survey’s most important lesson is this:

Before we reject something unfamiliar, we should make sure we know what it is.

News in the same category

A Heartwarming Tale of Workplace Compassion: A Father's 262 Days of Paid Leave

Debunking the Myth: Why Humans Did Not Evolve from Monkeys

The Hidden Climb of Thyroid Cancer in Younger Women

People Shocked After Finally Realizing What McDonald's Sweet 'N' Sour Sauce Is Really Made From

Eating Kimchi For 12 Weeks Helped People's Immune Cells Get Better At Spotting Viruses While Also Stopping Overreactions

Drunk Raccoon Turns Liquor Store into His Personal Bar Before Passing Out in the Bathroom

Turning Chicken Manure into Renewable Energy: The Netherlands' Circular Economy Solution

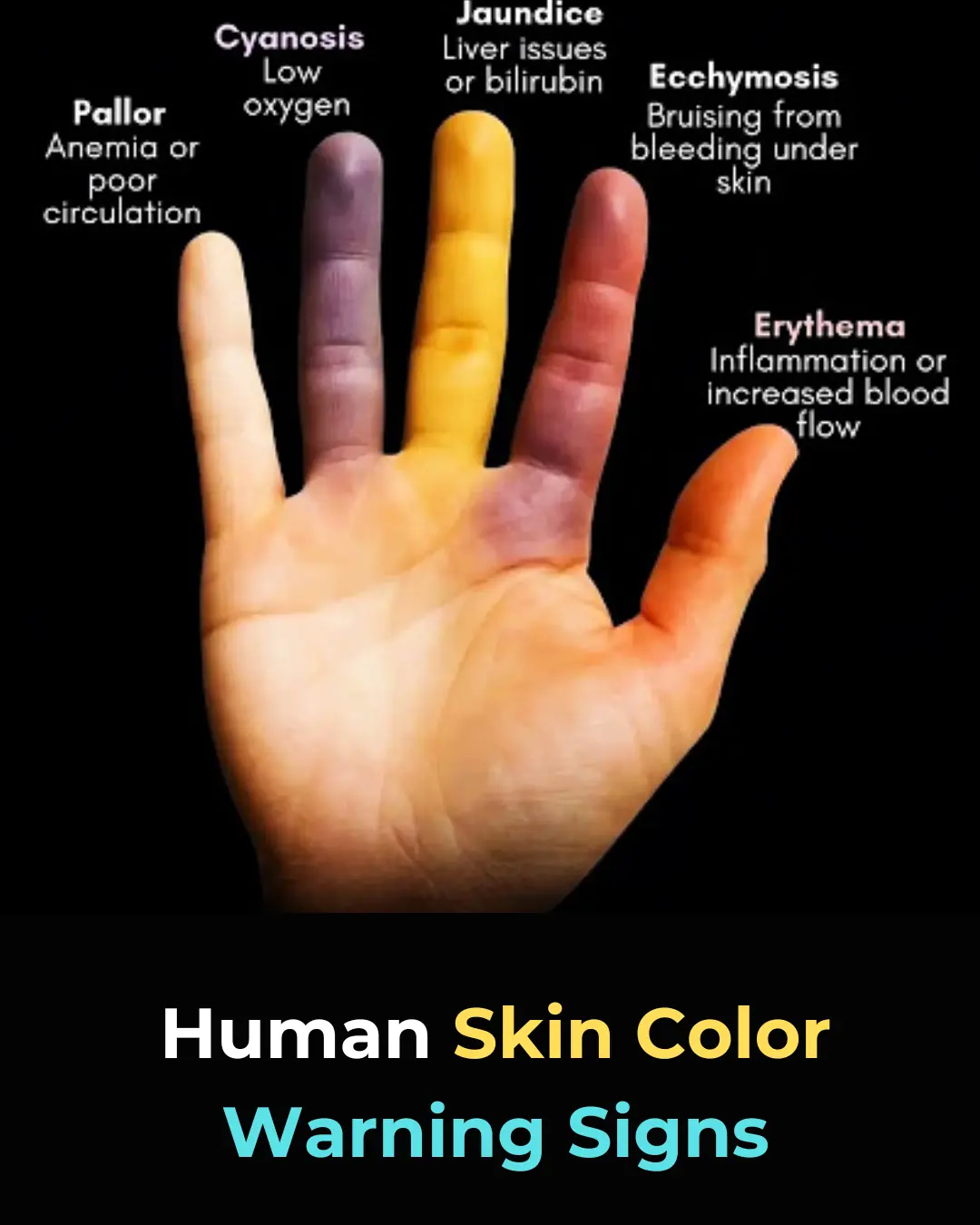

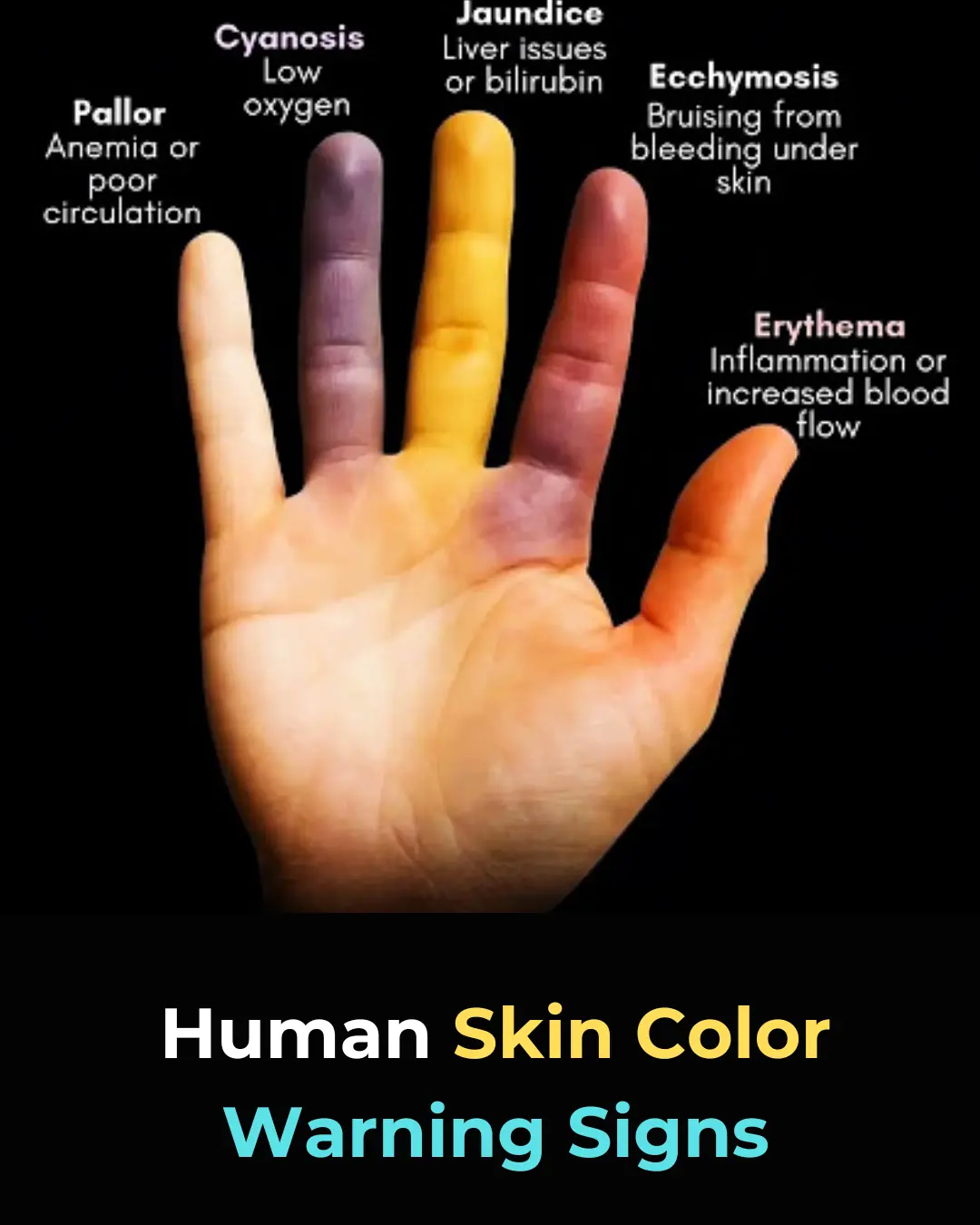

Understanding Skin Color Changes as Early Warning Signs of Health Issues

Rogfast Tunnel: Norway's Record-Breaking Undersea Highway Project

Expanding Human Perception: Exploring the Limits of Vision and Hearing Through Technology

CDC's Historic Decision to End Monkey Testing: A Shift Towards More Humane and Advanced Research Models

Teen Inventor Creates Battery-Free Flashlight Powered Only by Human Body Heat

The Boy Who Walked Through Ice: How Wang Fuman Inspired the World

From –4°F to Spring in Minutes: The Incredible 1943 Spearfish Temperature Shock

Saman Gunan: The Diver Who Gave His Life to Save the Wild Boars Team

From Circus to Sanctuary: Charley the Elephant Finds Freedom After Four Decades

10 Heartbreaking Reasons Children Stop Visiting Parents

8 Mind-Bending Optical Illusions That Test Your Level of Self-Awareness

News Post

Sip Your Way to Vibrance: The Ultimate Lipton, Cloves, and Ginger Tea for Women’s Wellness

Pumpkin Seeds: Nature’s Fierce Parasite Fighters for a Healthier Gut

Tamarind: A Promising Natural Solution to Help the Body Clear Microplastics

A Heartwarming Tale of Workplace Compassion: A Father's 262 Days of Paid Leave

Debunking the Myth: Why Humans Did Not Evolve from Monkeys

The Hidden Climb of Thyroid Cancer in Younger Women

From Rain to Runway: How Singapore’s Changi Airport Saves Over 8 Million Gallons of Water a Year

People Shocked After Finally Realizing What McDonald's Sweet 'N' Sour Sauce Is Really Made From

Eating Kimchi For 12 Weeks Helped People's Immune Cells Get Better At Spotting Viruses While Also Stopping Overreactions

Drunk Raccoon Turns Liquor Store into His Personal Bar Before Passing Out in the Bathroom

Turning Chicken Manure into Renewable Energy: The Netherlands' Circular Economy Solution

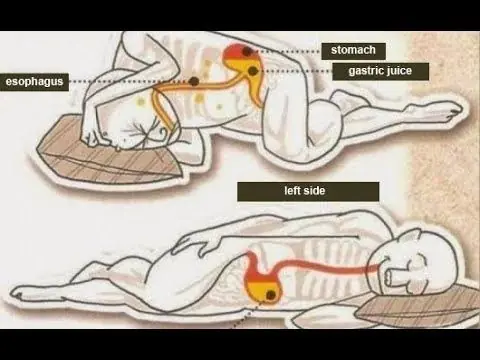

Why Sleeping on Your Left Side Is the Best Thing You’re Not Doing

Rising Tide of Change: The World’s Coastlines Are Entering a New Era

The Girl Who Said No — And Changed a Nation Forever

Understanding Skin Color Changes as Early Warning Signs of Health Issues

Rogfast Tunnel: Norway's Record-Breaking Undersea Highway Project

Expanding Human Perception: Exploring the Limits of Vision and Hearing Through Technology

CDC's Historic Decision to End Monkey Testing: A Shift Towards More Humane and Advanced Research Models