Why Quitting Alcohol Before 65 Is Essential for Protecting Your Brain Health

Why Quitting Alcohol Before Age 65 Is Critical for Long-Term Brain Health

In The Complete Guide to Memory: The Science of Strengthening Your Mind, neurologist Dr. Richard Restak underscores a powerful and often overlooked message: to protect brain health and preserve memory into older age, individuals should strongly consider giving up alcohol—including beer—before turning 65. While alcohol is often socially normalized, Dr. Restak emphasizes that it remains a mild neurotoxin, and its cumulative effects over decades can meaningfully impair cognitive function.

Alcohol’s impact on the brain becomes increasingly significant with age. Dr. Restak explains that drinking accelerates age-related neuronal loss, a natural but slow process in which brain cells gradually diminish over the lifespan. Although this decline is not abrupt, scientific studies estimate a 2–4% reduction in neuronal density over adulthood, meaning every remaining neuron becomes essential for maintaining memory, executive function, and learning capacity. As the aging brain becomes less resilient, alcohol’s neurotoxic properties intensify the risk of cognitive decline.

The danger is especially concerning because the likelihood of developing dementia—a condition affecting more than 55 million people worldwide, according to the World Health Organization (WHO)—rises sharply with age. Excessive or long-term alcohol consumption has been repeatedly linked to brain atrophy, particularly in areas responsible for memory and decision-making. Research published in The Lancet Public Health has shown that heavy alcohol use is a major risk factor for early-onset dementia, sometimes appearing before age 65.

Alcohol misuse can also trigger specific neurological disorders such as Wernicke–Korsakoff syndrome, a severe condition caused by Vitamin B1 (thiamine) deficiency, often associated with chronic alcohol consumption. The disorder leads to confusion, vision problems, coordination difficulties, and profound memory loss. The U.S. National Institutes of Health (NIH) identifies excessive alcohol use as one of the top contributors to this condition.

Memory loss, one of the earliest signs of dementia, can worsen significantly with alcohol intake. Dr. Restak warns that even moderate drinking after age 65 may heighten the risk of memory impairment. Several population-based studies—including those referenced by Alzheimer’s Research UK—have found correlations between alcohol consumption and increased likelihood of early-onset cognitive decline, particularly among individuals genetically predisposed to dementia.

Beyond cognitive risks, alcohol also presents serious physical dangers for older adults. Increased susceptibility to dizziness, impaired balance, and slower reaction times can lead to falls, fractures, and life-threatening injuries. The U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) reports that falls are one of the leading causes of injury-related deaths among adults over 65, and alcohol significantly heightens this risk.

Although some studies have proposed that light to moderate drinking might offer cardiovascular or cognitive benefits, the evidence remains inconclusive and inconsistent. Organizations such as Alzheimer’s Research UK caution that reducing alcohol consumption could help prevent or delay up to half of global dementia cases, especially when combined with other healthy lifestyle choices.

Public health guidelines reflect the uncertainty surrounding alcohol’s potential benefits. The UK National Health Service (NHS) recommends that adults limit consumption to no more than 14 units of alcohol per week, roughly equal to six pints of beer or one and a half bottles of wine. However, Dr. Restak maintains that complete abstinence after age 65 is the most reliable way to protect cognitive health.

The economic implications of dementia further underscore the importance of prevention. In the United Kingdom alone, dementia-related costs are projected to nearly double—from £43 billion to £90 billion—by 2040. Reducing alcohol intake could play a meaningful role in lowering these numbers by decreasing dementia incidence and associated long-term care expenses.

For individuals accustomed to occasional beer or social drinking, the suggestion to quit entirely may feel extreme. Yet Dr. Restak’s position is clear: aiming to stop alcohol use by 65, and certainly before 70, offers one of the most effective and scientifically supported strategies for preserving memory and cognitive health. The growing body of evidence shows that even seemingly harmless drinking can contribute to long-term harm, making timely lifestyle changes essential.

News in the same category

A Natural Pain Reliever for Legs, Varicose Veins, Rheumatism, and Arthritis

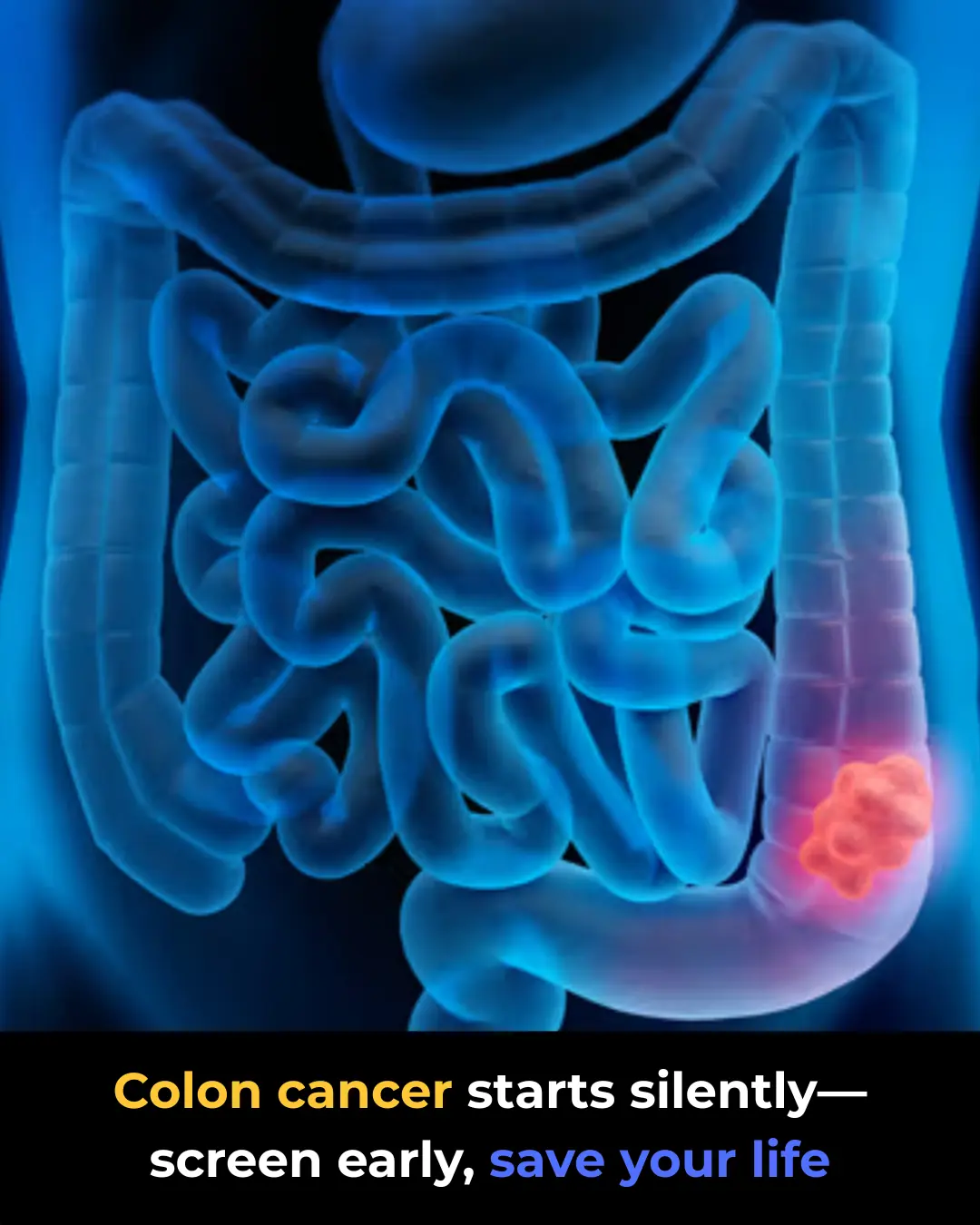

Colon Cancer: Why Early Screening Saves Lives

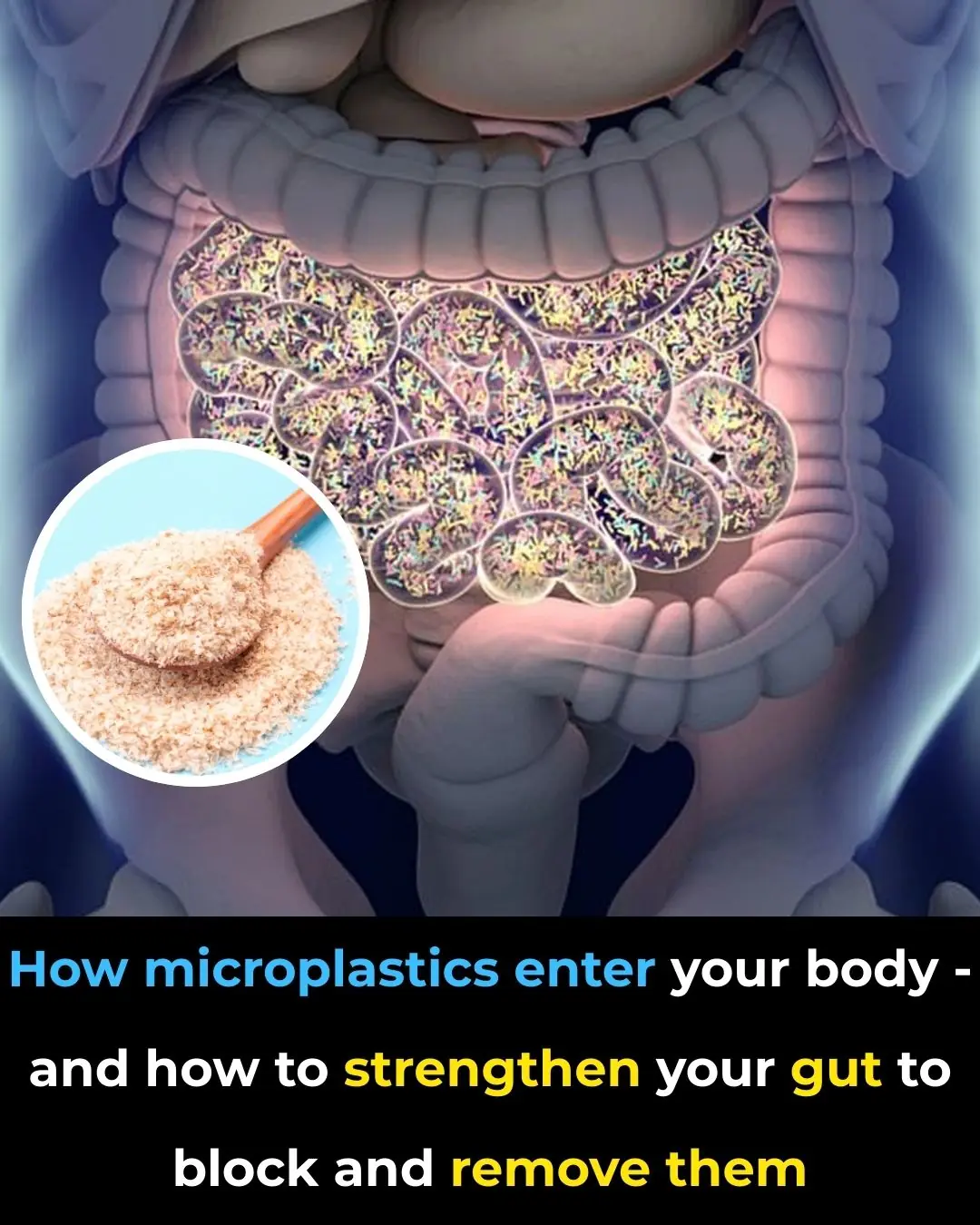

How Microplastics Enter Your Body — And How to Strengthen Your Gut to Block and Remove Them

Magnesium: The Benefits, the Risks, and the Safe Way to Take It — Especially for Your Kidneys

H. pylori Infection: Symptoms and How It Damages Your Stomach

7 Warning Signs Your Heart Isn’t Healthy — And 7 Symptoms You Should Never Ignore

Gastrointestinal Bleeding: Causes and Red-Flag Symptoms

16 Early Warning Signs Your Liver Is Sluggish And Toxins Are Being Stored In Your Fat Cells

The #1 way to flush microplastics from your body (It’s shockingly simple)

12 Foods That Protect the Heart in Surprising Ways

12 Herbal Remedies That Actually Work: Effective Natural Solutions for Common Ailments

Pulmonary Fibrosis: Early Signs and Treatment Options

Whooping Cough in Adults: The Unexpected Comeback

Tuberculosis Symptoms: What You Need to Know Early

🌿 How to Naturally Support Wart & Skin Tag Removal (Using a Simple DIY Remedy)

Doctors reveal the surprising reason your legs are the first to fail

🧄 Garlic’s Real Health Benefits — What Science Says About This Ancient Remedy

This One Simple Move at Night Stops Leg Cramping Fast

This ancient spice opens your arteries like magic and supercharges your heart

News Post

Two Teens Mock Poor Old Lady On Bus

The Spice That Protects: The Remarkable Health Power of Cloves

Ignite Unstoppable Mornings: The Banana–Coffee Elixir You Need Now

The Homemade Garlic & Lemon Secret to Strengthen and Lengthen Your Nails

4 Fruits You Should Eat in Moderation After Age 60 — And How to Enjoy Them Without Losing Muscle

Cloves to Eliminate Nail Fungus Naturally

A Natural Pain Reliever for Legs, Varicose Veins, Rheumatism, and Arthritis

Colon Cancer: Why Early Screening Saves Lives

How Microplastics Enter Your Body — And How to Strengthen Your Gut to Block and Remove Them

Magnesium: The Benefits, the Risks, and the Safe Way to Take It — Especially for Your Kidneys

H. pylori Infection: Symptoms and How It Damages Your Stomach

7 Warning Signs Your Heart Isn’t Healthy — And 7 Symptoms You Should Never Ignore

The Genius Reason People Pour Baking Soda Down the Sink — And Why You Should Too

Gastrointestinal Bleeding: Causes and Red-Flag Symptoms

16 Early Warning Signs Your Liver Is Sluggish And Toxins Are Being Stored In Your Fat Cells

Meet Our Cosmic Neighbor — The Andromeda Galaxy (M31)

The #1 way to flush microplastics from your body (It’s shockingly simple)

The Heartwarming Story of Alfred “Alfie” Date — Australia’s Oldest Man Who Knitted Sweaters for Injured Penguins

How Sahara Desert Dust Helps Fertilize the Amazon Rainforest — Even From 5,000 Miles Away